Featured Articles

How Black WWI Veterans Shaped The Civil Rights Movement

The hundreds of thousands of African Americans who served in the U.S. Army during World War I and returned home as heroes soon faced many more battles over their equality in American society. While they [...]

Bright Side of Dark Times: How WWI Forced Technological Advancements

When it comes to technology, a lot of things were developed during World War I. Some of these inventions were related to medical care, telecommunications, aircraft, ammo, tanks, and much more. World War I and [...]

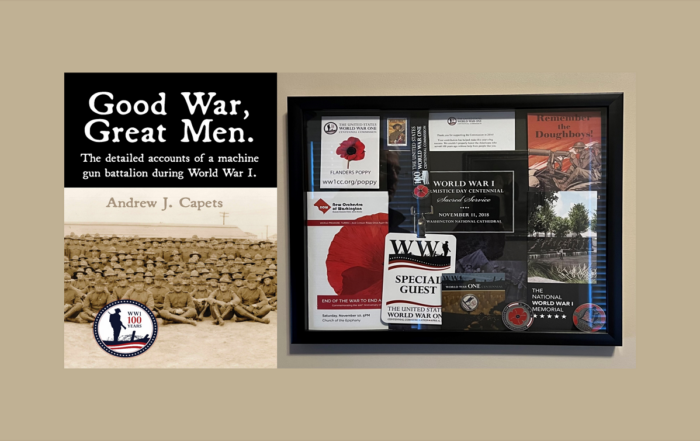

Sharing the stories and records of the Great War with others “creates a bond of admiration”

Thirty-one years after the Great War ended, a 67-year-old physician sat down and wrote a letter to his father recalling “one of the most trying days my young life had to that time experienced.” As [...]

During WWI, Missouri’s Home Guard filled in for the National Guard

The Great War depleted the states’ National Guard troops, sending them overseas. Missouri was one of the states that backfilled the domestic duties with unpaid volunteers. During World War I, Missouri was among a handful [...]

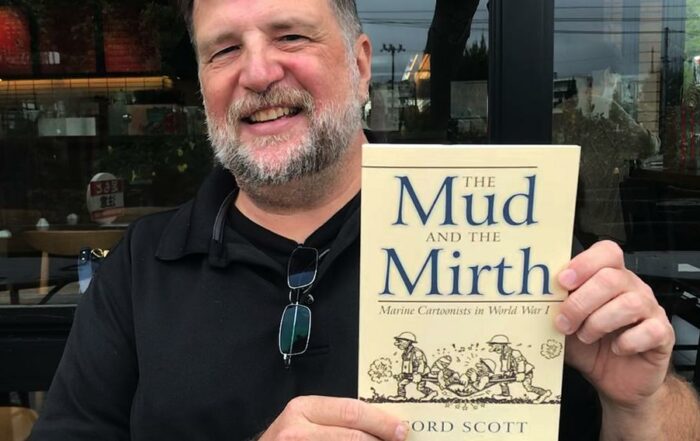

Professor mines Marine Corps history for book on WWI cartoons

CAMP FOSTER, Okinawa – History professor Cord Scott hopes his new book, “The Mud and the Mirth: Marine Cartoonists in World War I,” adds insight into the lives of ordinary Marine riflemen in World War I [...]

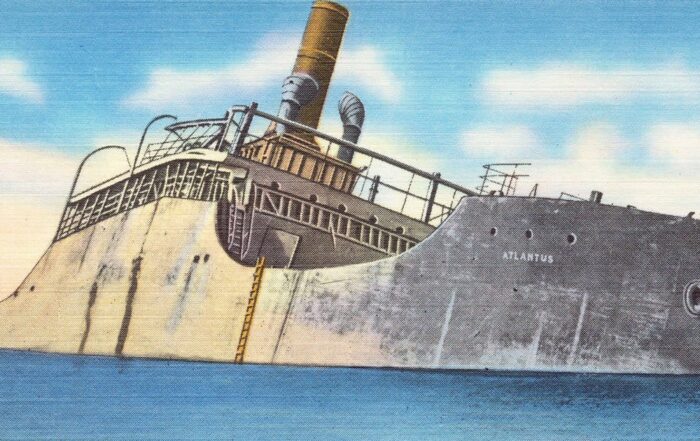

The US Navy built 12 concrete ships for World War I

During World War I, steel for building ships was in short supply. While American President Woodrow Wilson was determined to keep the U.S. out of the war, he didn’t want America’s Merchant Marine to be [...]

Historic Hangars of the Pacific Northwest

A weathered hangar at Jefferson County International Airport has housed plenty of aircraft maintenance and aviation history, all the way back to WWI. “How old is that hangar? It looks like something out of the [...]

Researchers studying whether some WWI vets were intentionally not honored

A Native American research facility in Arkansas is assisting in a project to determine if some U.S. military veterans who served during World War I did not receive honors they were due. The Sequoyah National [...]

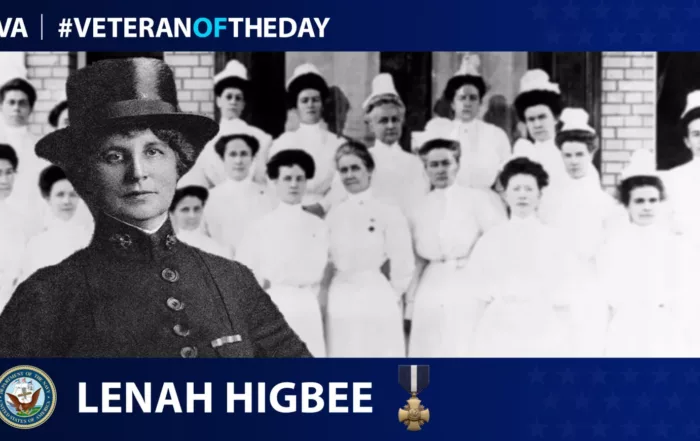

#VeteranOfTheDay: Navy Veteran Lenah S. Higbee

Originally from Chatham, New Brunswick, Canada, Lenah S. Higbee came to the U.S. to study nursing. She completed training at the New York Postgraduate Hospital in 1889 and began working as a surgical nurse for [...]