Family Research and Service Projects Lead to Better Understanding of Doughboy Heroes

Published: 11 January 2022

By Ann Silverthorn

Special to the Doughboy Foundation web site

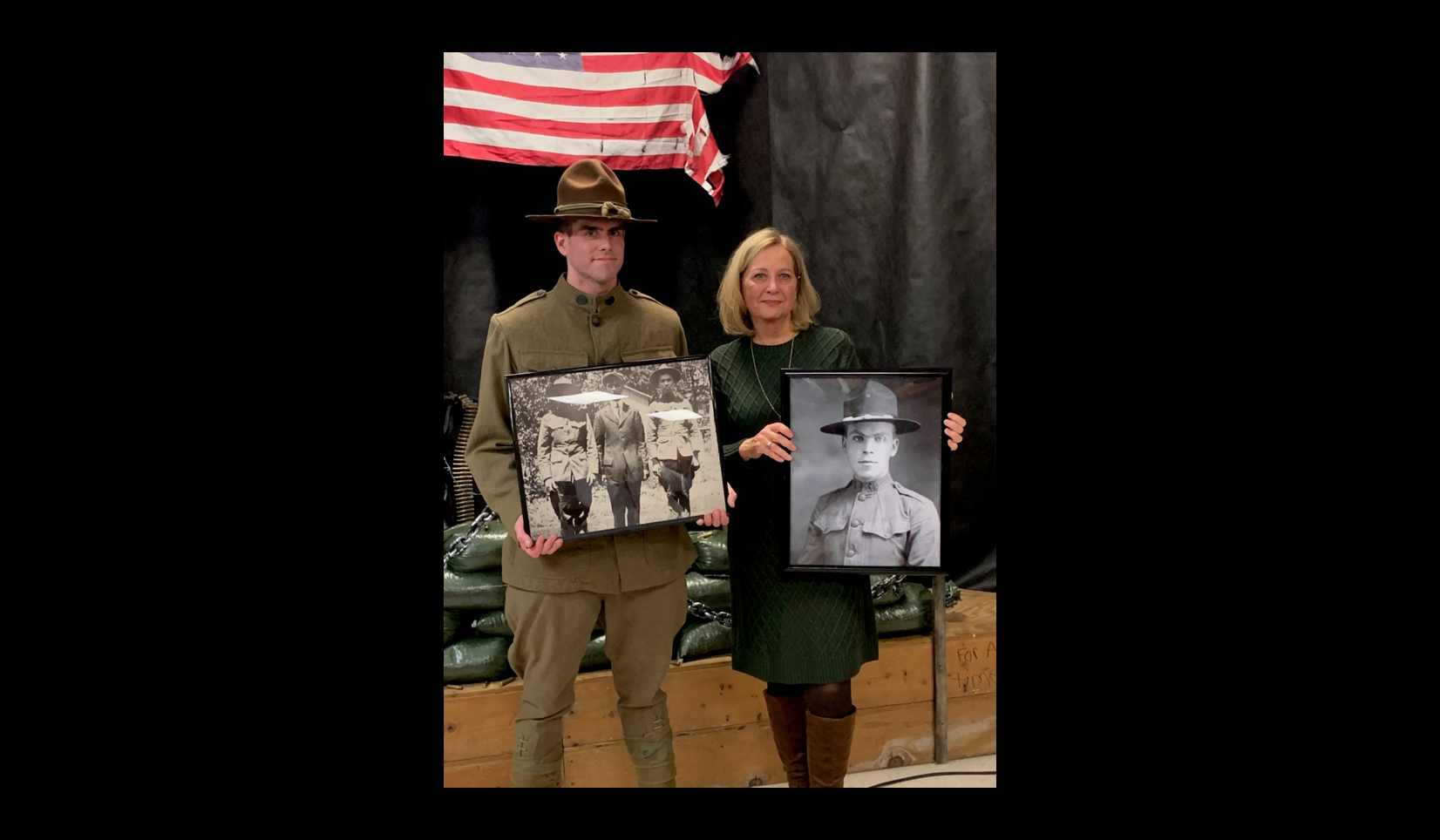

Header photo Silverthorn

Ann Silverthorn (right) and Rob Gatesman, who portrayed her grand uncle Russell Silverthorn in a play produced by American Legion Post 494 in Girard, Pennsylvania.

On November 13, 2021, I met my great uncle who died in France during World War I. To be more exact, I met the young man who personified my uncle in a local play called A Doughboy’s Story. Witnessing the living, breathing characterization of the young man who had previously been just a story to me was incredibly moving.

The project was originally planned as the 2019 program for the 100th anniversary celebration of American Legion Post 494 in Girard, Pennsylvania, but the pandemic caused a two-year delay. Instead, A Doughboy’s Story debuted at the post’s Veterans Day dinner in November 2021, and I was there.

My interest in World War I reaches back to a decade ago, when I started to research our family history. My father shared a piece of paper with me containing an image of Russell Worth Silverthorn, my grandfather’s brother. To the right of the image on the landscape-oriented page was a report from a “Mr. Scott” detailing Russell’s last hours in a hand-grenade torn French wine cellar.

PFC John Harding Scott, Jr., a medic from Bradford, PA, wrote that he and his partner had been captured by the Germans in Fismette, France. They convinced their captors to let them locate and treat the American soldiers who had been highly outnumbered by the Germans in the battle now known as the Tragedy at Fismette.

Scott wrote that he came upon an old wine cellar, or the remains of one, and found 24-year-old Russell Silverthorn, the only Doughboy among at least a dozen, who appeared to be alive. The soldiers had taken refuge underground and tried to defend their position in vain against the Germans, who tossed grenades through the opening. The medic bandaged my great uncle the best he could, but it was clear that the hole in his chest was fatal. Scott wrote that Russell had died like a man and that the men in the cellar had fought to the finish.

I was horrified at the monsters who had so coldly killed my great uncle, but not long after, I learned of another great uncle who died at age 19 in World War I. That revelation made me rethink the concept of enemy.

Many years ago, in her thick German accent, my late grandmother Catherine told me that her fiancé was killed in the war, but I don’t remember a mention of her brother. She did tell my Uncle Dan, who wrote a manuscript about Catherine’s early life in Germany, including details about her brother who had died in World War I.

Josef Wäschle

Josef Wäschle was killed by a French sniper’s bullet as he stood watch in an observation tower near Rheims. As Catherine’s mother watched her husband walking up the street after fetching a telegram, she said, “Joe’s dead.” She said she could tell by the way her husband walked.

Reading further how my great-grandmother wailed, I felt empathy for her and for my great uncle. I was sad about the horrors of war and how each of my uncles just wanted to stay alive. Just who was the enemy?

I wrote an impassioned piece for my blog about the concept of enemy. The regent of my Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) chapter, Mary Jane Koenig, thought I’d be interested in the committee she was organizing to honor Erie County, Pennsylvania’s involvement in World War I for the upcoming centennial in 2018. This involvement led me on a rewarding journey.

The Erie County World War One Centennial Committee raised money for a memorial that lists the names of the Erie County soldiers who sacrificed their lives in World War I. We consulted a book published in the 1920s that listed the names of 154 fallen soldiers from our area. Several members of the committee, including myself, researched the names, qualifying them for the memorial. Through our work, we discovered even more names, and the list grew to nearly 200.

With the generosity of grants and contributions, we dedicated the memorial on May 25, 2019. It is located in Veterans Memorial Park across from a stadium built in 1924 to honor those from Erie County who served and died in the First World War.

The “War Room” at Dan Edder’s funeral home in Girard, PA.

We had a target date for publication, but COVID-19 derailed the project for several months, before progress resumed with meetings taking place over video conferencing. Finally on May 25, 2021, two years to the day after the memorial dedication, we launched Answering the Call: Erie County in World War One at the Hagen History Center in Erie. A limited number of hard copies were printed with the remainder high-quality soft covers. The books were, and continue to be sold slightly below cost, thanks to the generosity of our donors. Proceeds support the improvement and preservation of the memorial.

A year before the book was published, Dan Edder contacted me about a project he was working for the 100th anniversary of the American Legion Post 494 in Girard, Pennsylvania. He was writing a play about World War I, and Russell Silverthorn was to be the main character. “I believed the play would have a great impact since he was from our area and to remember the horror those boys saw—that it was real,” Edder said.

Dan Edder has always been a history buff and read the 1919 book, With the 112th in France by James A. Murrin several times. This story of Doughboys in World War I reminded him of the photo of Russell Silverthorn displayed in the war room at his funeral home. He could see Russell in it all, especially in the chapter that details the bloody massacre at Fismette, where hundreds of American soldiers died or were taken prisoner.

To help Dan, I shared the concept-of-enemy blog post I had written with him and also the document my late uncle had written about Russell and his brother, Lee, in World War I. By July 2020, Edder had finished the script and started planning the production, but the American Legion anniversary celebration had to be cancelled because of the pandemic.

The play project had receded to the back of my mind, when in the summer of 2021, I received a message from Dan with a photo of a young man in a Doughboy uniform. The resemblance to my great uncle was uncanny. Dan said the young man would portray Russell in the Doughboy play.

The simple set of the Doughboy play.

The simple set of the Doughboy play.Now that the project was back in production, it was scheduled for November 13, 2021, when it would be performed during the American Legion’s Veterans Day program. I asked if I could attend, and Dan arranged for an invitation for my husband and me.

The night of the American Legion’s Veterans Day event was cold and rainy. Sloshing from the car to the building, even covered by an umbrella, left us chilled. I thought about the soldiers in the trenches . . .

After the military ceremonies, the meeting, and dinner, it was time for the play to begin. In a corner of the room sat a simple set consisting of a wooden platform bearing a heavy chain barrier, barbed wire, a French model 8mm machine gun, a folding wooden chair, and two large photos—one of Russell and one with Russell and his brothers, Lee and Burton (my grandfather). A tattered American flag hung from a simple black backdrop.

The 38-minute production featured narration, live musical interludes, and just one character—Russell Worth Silverthorn, played by a young area man named Rob Gatesman, who had served in the Pennsylvania Army National Guard. Through the narrators, one of whom was Dan Edder, the story of Company G, 112 Infantry, 28th Division was told.

Although Gatesman had never acted before, he flawlessly delivered the lines as Russell Silverthorn, painting a vivid picture from the perspective of a 24-year-old soldier—what it was like to travel from home to training, sail to England and France, ride the rails across France, and then march under a blistering summer sun.

The audience heard what it was like to be trapped under artillery fire in a small French village on August 27, 1918. The report from the medic, Mr. Scott, was read, including the following lines:

There I found Russell, still alive, but I soon found out that he would not live long as he was hit in several places and his worst wound was a hole in the left lung, where a piece of the grenade had pierced his lung, leaving a ragged hole, from which he was breathing. I knew there was no hope for him but bandaged him up the best I could.

At the end of the performance, the audience members were silent for an extended moment before they applauded and rose to their feet. It was clear that these military veterans and their guests had been greatly affected by the living, breathing doughboy’s story.

From his experience in the National Guard, he knew that Russell went to war alongside men from his community.

He deployed with men who walked the same streets, attended the same churches, and went to the same restaurants and bars. This is true of any National Guard unit that deploys to combat. I found this aspect of Russell’s story very striking, knowing that he likely grew up with many of his comrades. . . and that for many, their childhood friends didn’t make it home with them.

From researching and writing the play, Dan Edder realized how little he had known about the war—the suffering, huge losses, and indifference in sending thousands to death. “They were real people who suffered greatly for our benefit,” he said. “We as Americans today have no idea the price that has been paid for us to live our daily lives without fear.”

For myself, the performance was devastatingly moving. For the first time ever, my great uncle had become more than just a name with an unfortunate story. I keenly felt what Russell must have gone through, mourning his suffering and every other soldier’s at once. One tissue was not enough as I tried to keep my composure—and failed.

I’ve learned multitudes about World War I through my involvement with the Erie County Centennial Committee and through that having made the connection with Dan Edder and Rob Gatesman. Never could I have imagined how much I, and many others, would be affected by learning about World War I. The war that was once forgotten for so many, will never be so for us again.