The Decision That Changed The World – America’s Entry Into World War I

Published: 6 January 2022

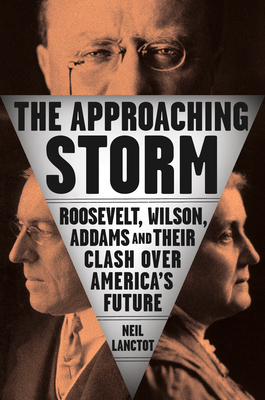

By Neil Lanctot

Special to the Doughboy Foundation web site

Delegates on Noordam for Chapter 4

Jane Addams (third from left) and pacifist colleagues on Noordam before departure, April 13, 1915. (Library of Congress, LC-B2- 3443-11).

“World War I? Why are you writing about that war?”

It was an all-too-common attitude I encountered when I shared with family and friends that my new book would explore America’s path to involvement in the Great War. Indeed, World War I, at least among the general public in the United States, remains a sort of red-headed step-child to more “popular” conflicts such as the Civil War and World War II. After all, America’s participation was fairly brief and our combat losses, compared to the European powers, were relatively light.

Neil Lanctot

But I had long been intrigued by World War I. Our Times, Mark Sullivan’s massive popular history of America in the early 20th century published between 1926 and 1935, had especially kindled my interest. Sullivan, a well-known journalist of the period, wrote from the perspective of a keen observer who had experienced the era firsthand and knew many of the major players. And his volumes on the World War I era were particularly fascinating, especially his coverage of the rapid changes occurring in America, the colorful political personalities, and the United States’ expanding global role.

But I had long been intrigued by World War I. Our Times, Mark Sullivan’s massive popular history of America in the early 20th century published between 1926 and 1935, had especially kindled my interest. Sullivan, a well-known journalist of the period, wrote from the perspective of a keen observer who had experienced the era firsthand and knew many of the major players. And his volumes on the World War I era were particularly fascinating, especially his coverage of the rapid changes occurring in America, the colorful political personalities, and the United States’ expanding global role.

I knew there was a story to be told, one that had long been overlooked. How did America come to make the fateful decision to join the Allies in 1917, a decision that actually changed the course of the 20th century? Without American involvement, Germany might never have been decisively defeated. In such an alternate scenario, there is no Treaty of Versailles to redraw the map of Europe, no reparations imposed on Germany, and no Hitler to set off a second World War twenty years later.

I felt the best way to tell this story was through a character-driven approach. The choice of the “characters” was not difficult. President Woodrow Wilson, ex-President Theodore Roosevelt, and the social worker and reformer Jane Addams not only knew each other well and were major figures in the Progressive reform movement of the early 1900s, but they were also deeply involved in the crucial episodes on America’s path to involvement.

More important, each represented a different perspective on how America should respond to the onset of the Great War. The pacifist Addams believed the United States should pursue any avenue to bring the belligerent nations to the peace table. Roosevelt, meanwhile, insisted that the war starkly revealed the very real threats potentially facing America in the future. To “TR,” he of the infamous “speak softly and carry a big stick” maxim, a nation with a modest 100,000 man army was helpless to protect herself or intervene against international wrong-doers.

Theodore Roosevelt and General Leonard Wood at Plattsburgh, New York, August 25, 1915 (Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-36425)

But the former academic Wilson was just as certain that America should maintain a “strict neutrality” while maintaining what he called its “self-possession.” If successful, then the United States would be ideally positioned to play a major role in the future peace process.

Woodrow Wilson marching in Washington preparedness parade, June 14, 1916 (Library of Congress: LC-H261- 7504)

Their disagreements notwithstanding, Wilson, Addams, and Roosevelt all recognized that this decision was incredibly important, perhaps the most important in American history up to that time. And each will do everything possible between 1914 and 1917 to steer the United States towards what they consider to be the “right” path, even at the expense of sacrificing their own personal popularity in the process.

Researching The Approaching Storm was a fascinating, albeit time-consuming task. The early twentieth-century was a time when much of the business of life was conducted by letter (many communities had multiple mail deliveries per day). Since Addams, Roosevelt, and Wilson kept up an active correspondence with colleagues, friends, and even strangers, thousands of letters between 1914 and 1917 had to be read and processed. It was also a time when many Americans kept detailed diaries, including Wilson’s friend and advisor, Colonel Edmund House. His diary provides a valuable first-hand account of not only the Wilson administration, but the movers and shakers in Europe, where House traveled several times during the war as the President’s personal envoy.

James Norman Hall, who served under the British, French, and American flags during World War I. (Grinnell College Libraries Special Collections)I supplemented the correspondence and diaries with a close read of the daily newspapers. In the World War I era, most large cities had multiple morning and afternoon newspapers, all with different political leanings. Because my three principal characters lived in Chicago, New York, and Washington, D.C., I carefully examined the daily newspapers of those cities published between the summer of 1914 and the American declaration of war in April 1917.

James Norman Hall, who served under the British, French, and American flags during World War I. (Grinnell College Libraries Special Collections)I supplemented the correspondence and diaries with a close read of the daily newspapers. In the World War I era, most large cities had multiple morning and afternoon newspapers, all with different political leanings. Because my three principal characters lived in Chicago, New York, and Washington, D.C., I carefully examined the daily newspapers of those cities published between the summer of 1914 and the American declaration of war in April 1917.

Inside these faded pages (later microfilmed or digitized), I found a treasure trove of captivating nuggets about the life and times of Americans in the World War I era. The polio epidemic of 1916, concerns over more revealing female bathing suits, and the Charlie Chaplin craze were just some of the issues attracting the attention of the average American during those years.

The newspapers also often reported on Americans who enlisted in the British or French forces long before the United States joined the Allies in 1917. Among them was a would-be author from Iowa named James Norman Hall. Once I learned that Hall had served under the British, French, and American flags during the war, I knew his story had to be included in The Approaching Storm. I eventually made extensive use of Hall’s often moving letters, which reveal a young man both repulsed and exhilarated by his combat experiences. Years later, Hall became famous as the co-author of the best-selling novel Mutiny on the Bounty.

One of the more interesting sources I uncovered were transcripts of wiretaps of German embassy officials authorized by the Wilson administration. These wiretaps revealed that Johann von Bernstorff, the German ambassador to the United States, was carrying on an affair with an American woman, as were several of his colleagues. Just as intriguing were transcripts of Roosevelt’s telephone conversations during the 1916 Republican and Progressive conventions in Chicago, secretly recorded by a stenographer at TR’s request so that he would not be “misquoted.”

Throughout my research and writing, I could not help but be reminded of our own time. The public and sometimes nasty battles waged between Addams, Roosevelt, and Wilson between 1914 and 1917 reveal an America just as divided as it is today. And the issues they fought over – America’s global responsibilities and how best to fulfill them – remain all too relevant in the 21st century.

Unfortunately, the Great War has been forgotten and ignored by too many Americans. My hope is that The Approaching Storm will restore America’s role in World War I to where it belongs: a major part of our collective memory as a nation.

Neil Lanctot is an American historian and author. He attended the University of Pennsylvania, graduating in 1987 with a B.A. in English, and later earned an M.A. in American History from Temple University in 1992 and a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania.