Inspired by Teaching History in England, I Explored the Unconventional Memorials Created by the Forgotten Female Veterans of World War I

Inspired by Teaching History in England, I Explored the Unconventional Memorials Created by the Forgotten Female Veterans of World War I

By Allison S. Finkelstein

Special to The Doughboy Foudation web site

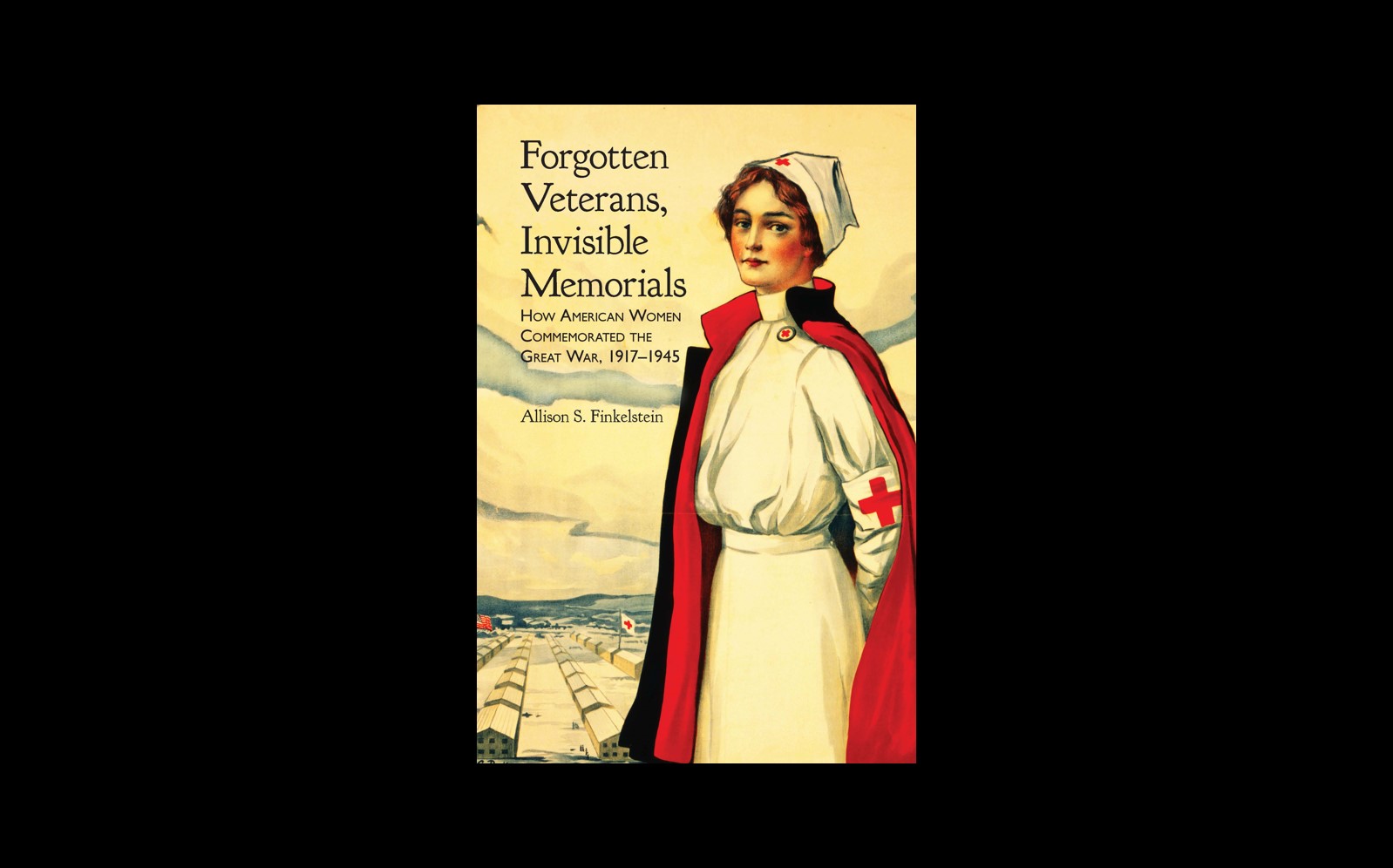

For any American who has been in Great Britain during the month of November, the enduring relevance of the memory of World War I in British culture is hard to miss. From the tradition of wearing a poppy to the nationwide two minutes of silence observed on Remembrance Sunday, many Britons remain deeply preoccupied with the Great War. After living among these rituals while teaching in the history department of an English boarding school, I started to wonder: why does the memory of World War I remain so much stronger in Great Britain than in the United States? This question led me on a long path to the publication of my first book: Forgotten Veterans, Invisible Memorials: How American Women Commemorated the Great War, 1917-1945. By investigating the groundbreaking role American women played in the memorialization of the war, the process of writing this book uncovered new ways to answer this question and revealed significant but too often overlooked aspects of World War I’s history that have renewed relevance today. Queen’s Cemetery in Puisieux, France, a British World War I cemetery run by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Photograph by Allison S. Finkelstein

Queen’s Cemetery in Puisieux, France, a British World War I cemetery run by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Photograph by Allison S. Finkelstein

The seeds for Forgotten Veterans, Invisible Memorials were planted during my time in England. After participating in British remembrance rituals and taking our students on a trip to the sites of the Western Front, I entered graduate school upon my return home. At the University of Maryland, College Park, I focused my studies on military commemoration. Two summers spent interning at the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC)—where I would later work—steered me firmly toward the First World War as my area of focus. I dove into this question about the American memory of the war through archival research as well as fieldwork at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial in France.

The seeds for Forgotten Veterans, Invisible Memorials were planted during my time in England. After participating in British remembrance rituals and taking our students on a trip to the sites of the Western Front, I entered graduate school upon my return home. At the University of Maryland, College Park, I focused my studies on military commemoration. Two summers spent interning at the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC)—where I would later work—steered me firmly toward the First World War as my area of focus. I dove into this question about the American memory of the war through archival research as well as fieldwork at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery and Memorial in France.

By the time I selected my dissertation topic, I knew enough to realize that answering this question was far too big for just one project. Instead, I decided to approach the question by specifically examining how American women commemorated the war. Doing so, I hoped, might provide some explanation of America’s waning memory of World War I. Little did I know that my research would do more than just shed light on answers to this question, but it would also help to resurrect a forgotten group of American women from the recesses of history. The more time I spent researching these women as I transformed my dissertation into a book, the more passionate I became about sharing their stories.

In its final form, Forgotten Veterans, Invisible Memorials investigates how American women who somehow served or sacrificed in World War I commemorated that conflict. I argue that these female activists considered their community service and veterans advocacy projects to be forms of commemoration just as significant and effective as traditional memorialization methods such as monuments and statues. In other words, these women sometimes preferred projects that helped a broadly defined group of male and female ‘veterans’ as an alternative to physical monuments and memorials. These are the invisible memorials mentioned in the book’s title.