SIDEBAR TEST Doughboy MIA for April 2023: First Lieutenant George Vaughn Seibold, 148th Aero Squadron

Published: 17 April 2023

By Daniel C. Williamson, Lieutenant Colonel, U.S.A. (Retired)

Aviation Lead – Doughboy M.I.A.

First Lieutenant George Vaughn Seibold, 148th Aero Squadron,

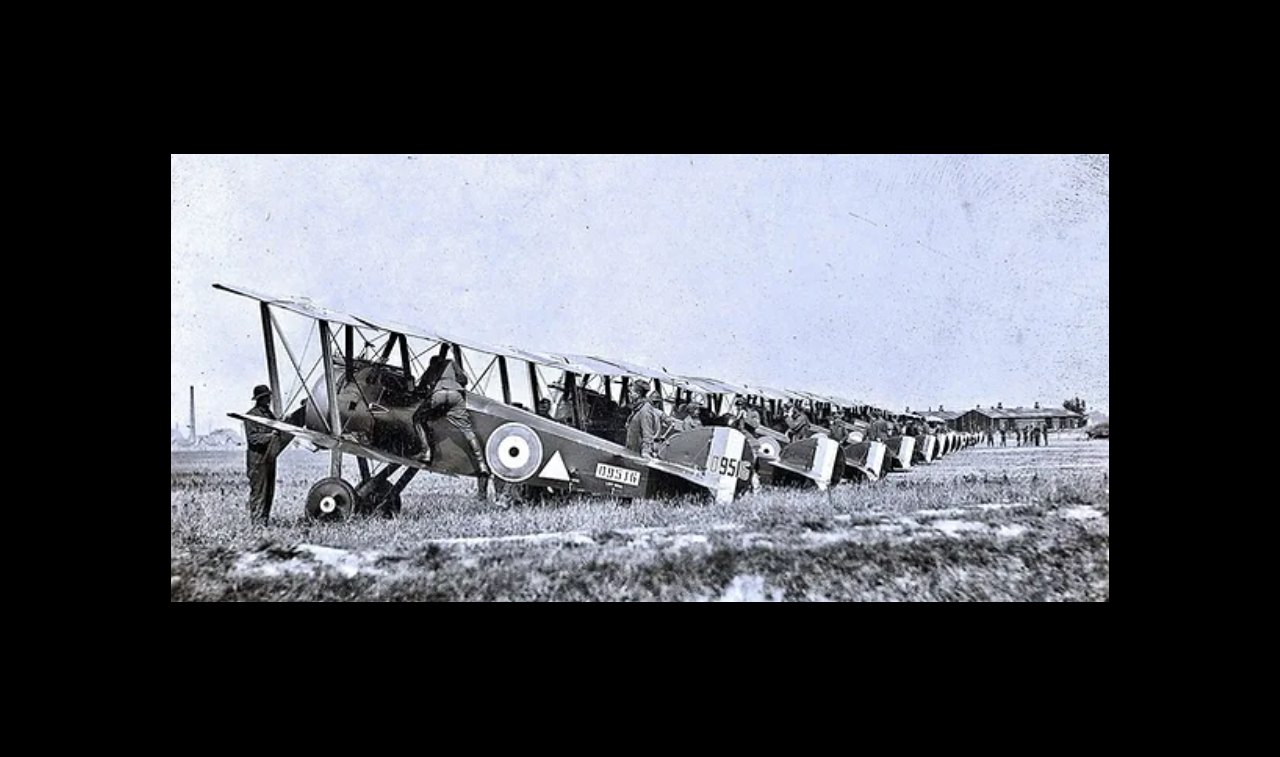

First Lieutenant George Vaughn Seibold, 148th Aero Squadron, and his last Camel D9516. Image from a film of the 148th Aero Squadron; it is believed that Seibold is the one on the wing climbing into the leftmost aircraft.

1LT George Vaughn Seibold

Our Doughboy MIA of the month for April 2023 is First Lieutenant George Vaughn Seibold, 148th Aero Squadron and grandson to two Union Officers in the Civil War, one who received the Medal of Honor leading an attack at Reams Stations, Virginia. First Lieutenant Seibold shot down two enemy aircraft while fighting for his survival on his last day. If he had survived his last aerial battle, and had the two victories been confirmed, his total enemy aircraft destroyed would be six, making him an American fighter ace.

George V. Seibold was born on 6 February 1893 in Washington D.C. to George G Seibold, a proofreader and linotype operator with the Washington Star and secretary of the Columbia Typographical Union, and Grace Darling (Whitaker) Seibold, daughter to Brigadier General Edward Washburn Whitaker (1st CT Cavalry). His family were prominently known Republicans in Washington circles. Grace Seibold being close friends with Grace Coolidge, wife to Calvin Coolidge, the wartime Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts and man who would be Vice President (1921-1923) and then President (1923-1929).

George V. Seibold was known as kind, protective of his siblings, fun loving, easy-going, and charming. He was a good student and capable athlete. Popular with his classmates, George Seibold graduated from Washington’s Central High School enrolled in the McKinley Manual Training School instead of attending a university. In 1912 he worked in the Government Printing Office and then as the private secretary to Congressman Dr. Thomas Nelson Page. George Seibold then moved to Chicago to work in a law firm of a family member but left that employment to work as a real estate broker for Aldis & Company. He would work there for four years only leaving in 1917 to fight for the United States in Europe.

While at Aldis & Company he attended the first Reserve Officer’s Training Camp in Plattsburgh, New York in 1916. His many positive traits made him ideal leadership material and as a result received an evaluation as an excellent candidate to become an Army Officer. During his time in Chicago he met and began dating his future wife, Kathryn Irene Benson, a fellow Aldis & Company employee.

On 2 April 1918 the United States declared war on German and George V. Seibold entered the Officer’s Reserve Corps Training Camp at Fort Sheridan, Illinois in July 1917. Before the end of that month, he would find out he was accepted into the Army’s Aviator training program. He immediately purposed marriage to Kathryn on 17 July 1917, and married four days later. They would spend a day and a half together before he departed for Toronto, Canada to begin his flight training.

Reporting into the Long Branch Aerodrome, just west of Toronto on Lake Ontario, Cadet George V. Seibold was officially an Aviator Trainee learning to fly at Royal Flying Corps flight schools. Within the first week Cadet Seibold received courses in airframes, engines, navigation, Morse code, and dual-control take-offs and landings. He was an apt student and became the first from the Fort Sheridan group of Cadets to solo. Then he was thrust into more training on how to perform loops, banks, glides, stalls, formations flying, Chandelles and Immelmann turns. Once mastering these tasks Cadet Seibold received still more training on dropping bombs, gunnery, and aerial photography. This completed his primary flight training and then he was sent to Advanced Flight training in Texas.

Sidebar Title

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas.

During his training in November 1917 in Texas, George Seibold had a close call. While testing a new aircraft at 2,500 feet it inexplicably fell into an uncontrolled nosedive. Unable to recover control of the plane, the quick thinking Seibold throttled back his engine and shut it off completely. When the aircraft plunged into the ground it did not explode and Cadet Seibold was able to escape certain death with only scars on his right cheek and right hand. His quick actions led to his assignment as a flight instructor for new pilots until 1 December 1918 when he was commissioned a First Lieutenant, Reserve Aviator and thereafter departed for the port at Hoboken, New Jersey.

The RMS Adriatic manifest has First Lieutenant George V. Seibold list as part of the 22nd Aero Squadron when it departed for Europe on 31 January 1918. German U-Boats prowled the sea lanes and there was a very real threat to the ships in the convoy being sunk. In a letter to his mother, he reported on 5 February 1918 at 5:42 P.M. seeing the ship in front of RMS Adriatic, the SS Tuscania, take a torpedo and sink before reaching Liverpool. The attack came from UB-77 which fired two torpedoes, only one hitting the Tuscania. The mortally wounded transport ship went down at 10 P.M. that same night with 230 American souls lost. Among those lost were many support personnel from the 100th, 158th, and 213th Aero Squadrons.

Once in Europe Lieutenant Seibold was sent to Oxford to complete ground school. A course that they had completed in Canada months before. Next was training on British Avros, Sopwith Pups, and Camels at Salisbury Plain. Mastering these airframes, Lieutenant Seibold, and the rest of 22nd Aero Squadron were sent to gunnery training near Turnberry, Scotland and then to the School of Aerial Fighting in Ayr, Scotland. After completion Lieutenant Seibold and his fellow pilots were considered ready for assignment to combat squadrons. On 30 June 1918 1Lt George Vaughn Seibold received orders assigning him the newly formed 148th Aero Squadron flying Sopwith F1 “Camels.” The 148th Aero Squadron, along with the 17th Aero Squadron, another new American Camel squadron, were attached to the Royal Air Force’s 13th Wing, controlled by the Third British Army.

Lieutenant Seibold reported to the 148th Aero Squadron on 3 July 1918 with three other pilots, 1LT William T Clements, 2LT Thomas M. Galbreath, and 2LT Oscar Mandel. Of the four only George Seibold would fail to survive the war.

148th Aero Squadron Emblem

Not much is known about Lieutenant Seibold’s first days in the 148th Aero Squadron. What is clear is that he was assigned to “A” Flight along with First Lieutenants Lawrence Wyly, Walter Knox, Jesse O. Creech and Field Kindley. Lieutenant Kindley was assigned as the leader of “A” Flight as he had already seen combat with the RAF’s 65 Squadron and shot down the four victory Jasta 5 Commaner on 26 June 1918.

1LT Seibold immediately had problems crashing his first Camel on 9 July 1918 at the Dunkirk aerodrome but escaped without injury. Undaunted he was in the air the next day at 4 A.M. to fly a “line patrol” with fourteen other pilots of the Squadron to understand the surround area and the front lines. During that flight Lieutenant Seibold and nine other Squadron members were caught in heavy thunderstorm but all returned safely. The next day the Squadron continued “line patrols” and even began taking anti-aircraft fire as they crossed over the lines. These continued until the 1LT Kindley shot down a German Albatross D-3 on 13 July 1918 to get the Squadron’s first official victory. The 148th Aero Squadron was then determined to be a combat ready squadron and began active patrolling.

But Lieutenant Seibold’s continued to have problems. On 3 August 1918, 1LT Seibold was admitted to Queen Alexandria Hospital. The reason why isn’t exactly clear. But that same day, during a patrol an engagement ensued with a flight of enemy Fokker aircraft. During the air battle the “A” Flight Leader, 1LT Kindley, attacked an enemy aircraft that was shooting at one the members of his flight. Kindley was successful in shooting down the enemy Fokker and saved the life of one of the members of his flight. This in all probability was 1LT George V. Seibold as he was forced to crash his Camel, escaping with slight injuries. But the injuries were of such a nature it would cause him to spend five days in the hospital before returning to combat duty. Soon afterwards Lieutenant Seibold would enjoy more successful missions.

From 13 August 1918 to the end of his life on 26 August 1918, Lieutenant Seibold would shoot down four confirmed enemy aircraft and two unconfirmed. During the same period, he completed many dangerous ground strafing missions. Lieutenant Seibold would also be considered the pilot who ended the successful flying career of the younger brother of the “Red Baron” Manfred von Richthofen. Oberleutant Lothar Siegfried Freiherr von Richthofen the day before had shot down two Sopwith Camels to bring his score to 40 victories. Lothar von Richthofen was known to have been shot down by a 148th Aero Squadron pilot on 13 August 1918. Lieutenant Seibold was credited with shooting down an enemy Fokker that same day. In actuality it may have been the combined efforts of Lieutenant Seibold and Lieutenant Kindley that brought down the brother of the Red Baron.

Two days later, on 15 August 1918, Lieutenant George V. Seibold shot down another Fokker Biplane at 4:30 P.M. northwest of Chaulnes. Ten days after that, on his second mission of the day, Lieutenant Seibold shot down a German Hanover CLIII south of Halpincourt at 6:10 in the evening.

26 August 1918 would prove to be Lieutenant George V. Seibold’s final mission. Sergeant Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary entry on that day states “Allies on outskirts of Bapaume and slowly but surely making progress. Heavy rains today. No flying until evening. Ground strafeing (sic). LT. SEIBOLD WENT “WEST”.” Lieutenants Creech and Seibold, flying as a team, dropped their bombs northeast of Bapaume then turned to find other targets. Creech observed a large fight of eleven aircraft halfway between Bapaume and Cambrai. Then he watched as three Fokkers shot down a Camel west of Vaulx-Vraucourt. The Squadron’s written history states Creech and Seibold were surprised by Fokkers from above. Lieutenant Creech made his way home nursing a badly shot up Camel. Lieutenant Seibold did not return.

That day German attacks on ground strafing allied aircraft was intense. The 13th Wing Commander called out the 17th Aero Squadron to help protect the 148th Aero Squadron. At the time the 148th Aero Squadron were being attacked by a heavy force of German Fokkers along the Bapaume – Cambria Road. At about 5 P.M. First Lieutenant W.D. Tipton and 2LT R.M. Todd reported seeing a lone Camel “being attacked by 5 Fokkers . . . at about 57c.B. at 1000 feet.” Tipton and Todd were both shot down and captured after engaging another flight of Fokkers, but this lone Camel fighting off five Fokkers was most certainly George Seibold as is stated in the official history of the 17th Aero Squadron.

Witnessing from the ground was Lieutenant James B. Edwards, a South African pilot of 64 Squadron, Royal Air Force. He was there after his SE5a was hit by ground fire. The aircraft’s main petrol pipe was shot through, and he was forced to land within allied lines between Behagnies and Sapignies. This was just north of where Seibold’s Camel came down. In a letter dated 3 November 1918 he reported “After a short but sharp scrap one (1) Camel came down out of control, followed by the hun, who was firing the whole time. The Camel eventually crashed about 200 yards from me, being absolutely wrecked. I rushed out to see if I could aid the pilot in any way, but unfortunately, he was dead.” To identify the pilot, Lieutenant Edwards pulled a ring of the finger of the dead aviator to discover it was a wedding ring with George Seibold’s initials and his wife’s initials engraved on it. Seibold’s aircraft was upside down and Lieutenant Seibold was folded up inside the wreckage. Lieutenant Edwards could not get more access to Siebold’s pockets to find his identity papers. At the time Lieutenant Edwards stated the area was taking enemy artillery fire and he could not remain near the wrecked Camel long.

Two days later, on 15 August 1918, Lieutenant George V. Seibold shot down another Fokker Biplane at 4:30 P.M. northwest of Chaulnes. Ten days after that, on his second mission of the day, Lieutenant Seibold shot down a German Hanover CLIII south of Halpincourt at 6:10 in the evening.

26 August 1918 would prove to be Lieutenant George V. Seibold’s final mission. Sergeant Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary entry on that day states “Allies on outskirts of Bapaume and slowly but surely making progress. Heavy rains today. No flying until evening. Ground strafeing (sic). LT. SEIBOLD WENT “WEST”.” Lieutenants Creech and Seibold, flying as a team, dropped their bombs northeast of Bapaume then turned to find other targets. Creech observed a large fight of eleven aircraft halfway between Bapaume and Cambrai. Then he watched as three Fokkers shot down a Camel west of Vaulx-Vraucourt. The Squadron’s written history states Creech and Seibold were surprised by Fokkers from above. Lieutenant Creech made his way home nursing a badly shot up Camel. Lieutenant Seibold did not return.

That day German attacks on ground strafing allied aircraft was intense. The 13th Wing Commander called out the 17th Aero Squadron to help protect the 148th Aero Squadron. At the time the 148th Aero Squadron were being attacked by a heavy force of German Fokkers along the Bapaume – Cambria Road. At about 5 P.M. First Lieutenant W.D. Tipton and 2LT R.M. Todd reported seeing a lone Camel “being attacked by 5 Fokkers . . . at about 57c.B. at 1000 feet.” Tipton and Todd were both shot down and captured after engaging another flight of Fokkers, but this lone Camel fighting off five Fokkers was most certainly George Seibold as is stated in the official history of the 17th Aero Squadron.

Witnessing from the ground was Lieutenant James B. Edwards, a South African pilot of 64 Squadron, Royal Air Force. He was there after his SE5a was hit by ground fire. The aircraft’s main petrol pipe was shot through, and he was forced to land within allied lines between Behagnies and Sapignies. This was just north of where Seibold’s Camel came down. In a letter dated 3 November 1918 he reported “After a short but sharp scrap one (1) Camel came down out of control, followed by the hun, who was firing the whole time. The Camel eventually crashed about 200 yards from me, being absolutely wrecked. I rushed out to see if I could aid the pilot in any way, but unfortunately, he was dead.” To identify the pilot, Lieutenant Edwards pulled a ring of the finger of the dead aviator to discover it was a wedding ring with George Seibold’s initials and his wife’s initials engraved on it. Seibold’s aircraft was upside down and Lieutenant Seibold was folded up inside the wreckage. Lieutenant Edwards could not get more access to Siebold’s pockets to find his identity papers. At the time Lieutenant Edwards stated the area was taking enemy artillery fire and he could not remain near the wrecked Camel long.

Two months later, on 23 October 1918, Lieutenant Edwards was able to confirm the identity of the Squadron the Camel belonged to during a discussion with First Lieutenant Errol H. Zistel of the 148th Aero Squadron’s “C” Flight. Lieutenant Edwards then gave Seibold’s ring to Lieutenant Zistel to make sure it got back to the family. Lieutenant Zistel gave the ring to Captain George Dwyer, United States Air Service when he was later sent to England.

148th Aero Squadron members attempted to locate Lieutenant Seibold’s aircraft and remains flying over the area and later during personal search of the area on the ground by the Squadron Commander The search produced no trace of Lieutenant Seibold’s grave or the wreckage of his Camel. The day after the loss of Lieutenant Seibold the 148th Aero Squadron submitted a report to the RAF stating he was missing in action. The RAF headquarters wasted no time and sent a letter to the Chief of the Air Service, American Expeditionary Force in Tours, France stating as of 26 August 1918 First Lieutenant George V Seibold was officially missing. However, for some reason Lieutenant Seibold’s name was not officially struck off the Squadron’s rolls until 16 September 1918.

For some reason the immediate family of Lieutenant Seibold was not notified that he was missing in action. His wife Kathryn had received his last letter dated 24 August 1918, but it wasn’t until 11 October 1918 that she knew something was truly wrong. On that day she received a carboard container marked “Effects of deceased officer 1LT GV Seibold.” The box contained the personal belongs of the pilot left at the 148th Aero Squadron. She immediately wired her Washington D.C. in-laws about the box and the news.

Grace Darling Seibold, mother of George Vaughn Seibold. Image courtesy The Gold Star Mothers, Inc.

Lieutenant Seibold’s mother, Grace, began an immediate search of military hospitals in the Washington area in a hope of locating her son. Her efforts did not produce her son, only more questions. The concern and questions of the Seibold family went unanswered until as late as 30 November 1918. Senator Robert L. Owen of Oklahoma intervened on their behalf, producing an official notification that their son was indeed missing in action and was “last seen flying east of Bapaume.” On 13 December 1918 the family received a letter stating George had been officially reported as “Killed in Action” and was lost behind enemy lines.

Having official notification only mobilized the Seibold family’s resolve. Their entire purpose was to locate their son’s grave. The powerful reach of the Seibold family included Lieutenant Seibold’s uncle, Louis Seibold, a journalist in Paris for the New York World and his influential paternal grandfather Brigadier General Edward Washburn Whitaker. Lieutenant Seibold’s uncle contacted the United States Army Provost Marshal for assistance, while his grandfather wrote directly to the U.S. Secretary of War, Newton D. Baker, and General John J. Pershing admonishing them for the lack of information about his Grandson’s grave. Both, despite being high ranking American officials, felt the hard sting of a Civil War combat veteran and Medal of Honor awardee’s words. General Whitaker wrote, the “Red Cross having recently report that the Lieutenant fell inside of our lines the delay in the partial and conflicting reports is astounding to one like myself, who served from Bull Run to Appomattox, under officers of the Regular Army, and learned to admire their intelligence and strict enforcement of army regulations requiring the promptness and accuracy in reports from all branches of the service.”

Six months later General Whitaker again wrote the Secretary of War. This new letter was even less kind and biting as his grandson’s grave was still unknown. “It seems incredible that your great department with all the appropriations and organizations, has thus far failed to locate the grave of my grandson killed in action August 26, 1918, a year ago today! Will you now order an investigation and report?”

The search for Lieutenant Seibold’s grave did continue under such pressure. Yet still, a careful search of the Bapaume area and the records of the British Commonwealth Graves Commission yielded nothing leading to the whereabouts of George V. Seibold’s grave. Eventually Lieutenant Seibold’s father received a letter from the Cemeterial Division of the Quartermaster General Department stating they believed Lieutenant Seibold was buried in American Cemetery 176. Unfortunately, a check of Lieutenant Seibold’s dental records proved this assumption to be wrong as they matched no unknown remains. In 1922 Lieutenant Seibold’s dental records again proved an unknown aviator’s grave was not that of George V Seibold. Based on this last event Grace Seibold demanded more information of her son’s last day. For the first time the Seibold family learned of Lieutenant Zistal and Lieutenant Edwards’ meeting and of finding Lieutenant Seibold’s ring.

In early summer of 1923, another unknown aviator’s body was found. In a brazen attempt to appease the Seibold family and General Whitaker it was suggested in a series of memos that the remains be presented as Lieutenant Seibold’s. The remains were in such a state that at the time there was no positive way of being identified as Lieutenant Seibold’s. Despite the fact these remains were found near the suspected location of Lieutenant Seibold’s aircraft crash. The American Graves Registration Service officially gave up on ever finding Lieutenant Seibold’s grave on 19 April 1927. A memorandum declared “unless precise burial data is available or can be obtained, at this time it is believed further physical search should not be made until more definite information as to the grave location is furnished.”

In tribute to her son, Grace Seibold became one of the main driving forces behind the “Gold Star Mothers.” An organization of women who had lost sons and daughters in World War One. Her belief the symbol of the gold star was “the last full measure of devotion and pride of the family” and its sacrifice. She would become the first President of the influential organization who would go on to dedicate themselves to support U.S. war veterans and the families of fallen service men and women. Grace Seibold’s efforts and her friendship with President Coolidge’s family help lead the effort to have the government pay for the bereaved mothers to visit the graves of their sons in Europe.

Doughboy MIA has an Aviation Team dedicated to locating missing in action American Aviators of World War One. Lieutenant Sebold’s MIA case is actively being researched by this team with the goal of finding and repatriating his remains. Until accomplished, First Lieutenant George Vaughn Seibold is listed on the Tablets of the Missing, Somme American Military Cemetery.

Want to help? Make a donation today to Doughboy MIA! YOU can be part of the recovery efforts!

Sidebar Title

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur. Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident, sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum.

Sed ut perspiciatis unde omnis iste natus error sit voluptatem accusantium doloremque laudantium, totam rem aperiam, eaque ipsa quae ab illo inventore veritatis et quasi architecto beatae vitae dicta sunt explicabo. Nemo enim ipsam voluptatem quia voluptas.