Discovery of an Archival Photograph Results in an Unlikely Connection between a WWI Collier and a Destroyer

Published: 3 October 2025

By Marvin Barrash

Special to the Doughboy Foundation website

USS_Cyclops_in_Hudson_River_19111003

USS Cyclops on the Hudson River in 1911.

The Research

For more than a quarter century I’ve researched the U.S.S. Cyclops. When I began the quest to learn about the ship and her personnel, Internet web browsing was still in its infancy. It was full of promise, but it was not yet a reliable document source. I relied on actual visits to libraries and repositories and viewed original source materials such as paper documents and ships’ log books. Sometimes scratchy microfilms were the only alternative to paper originals. With the passage of time, the Internet grew in volume and in speed. Bigger and faster were not necessarily better. Online repositories began to appear, but few were dependable. The standards and formats for digital data, networks and systems constantly changed and evolved.

Once I knew that I would commit to write a history of the U.S.S. Cyclops, I needed to have frequent and easy access to the ship’s log books. It was not practical for me to make frequent trips to Washington, D.C. to study and make notes from those volumes at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), the repository for those and most U.S. Navy log books. Also, I wasn’t yet familiar with the types of entries or data that those log books contained. I opted to have the ship’s physical log book volumes copied. The only means made available to me by NARA was to have the pages microfilmed.

All of the ship’s log books fit on 5 reels of 35mm film. Since I didn’t have a microfilm reader and believed that the pages would be more useful through a desktop computer, I then had the films digitized. With full-time access to the most important data from the ship, a major hurdle was cleared.

My first volume, U.S.S. CYCLOPS [vol. 1] took 13 years to complete. Throughout its development. I welcomed the increase of online historical documents not only by NARA, the Library of Congress (LoC), and materials made available from other government and private organizations.

The weak link in the research was and continues to be how to zero in on just what I’ve needed. Unlike a physical library, one cannot simply browse the shelves. Search terms are essential. I’ve seen search engines come and go. Some were better than others; none have been perfect. I’m not only referring to the massive Google search tool, but to the catalogs that the aforementioned NARA and LoC make available through their websites. Sometimes those catalogs yielded some interesting and beneficial surprises.

Such was the case, five years ago. I happened to go on a renewed search through the NARA Catalog for unpublished images of the collier Cyclops. Nothing of substance resulted initially. After deleting the name “Cyclops” from the search, I inserted modifications of “navy yard” as search terms. Listings for some unusual photos of ships were revealed as available in digital form. The collier showed up in several photos that I’d not seen before. These images were taken over a period of several years at a couple of Navy yards. They were unusual in that the photographer did not intend to photograph the collier or other ships. These were actually glass-plate photos taken of facilities work by contractors at the yards to show the progress of their projects; the ships just happened to be in these views. These photographs were well-annotated with the date and location of each view.

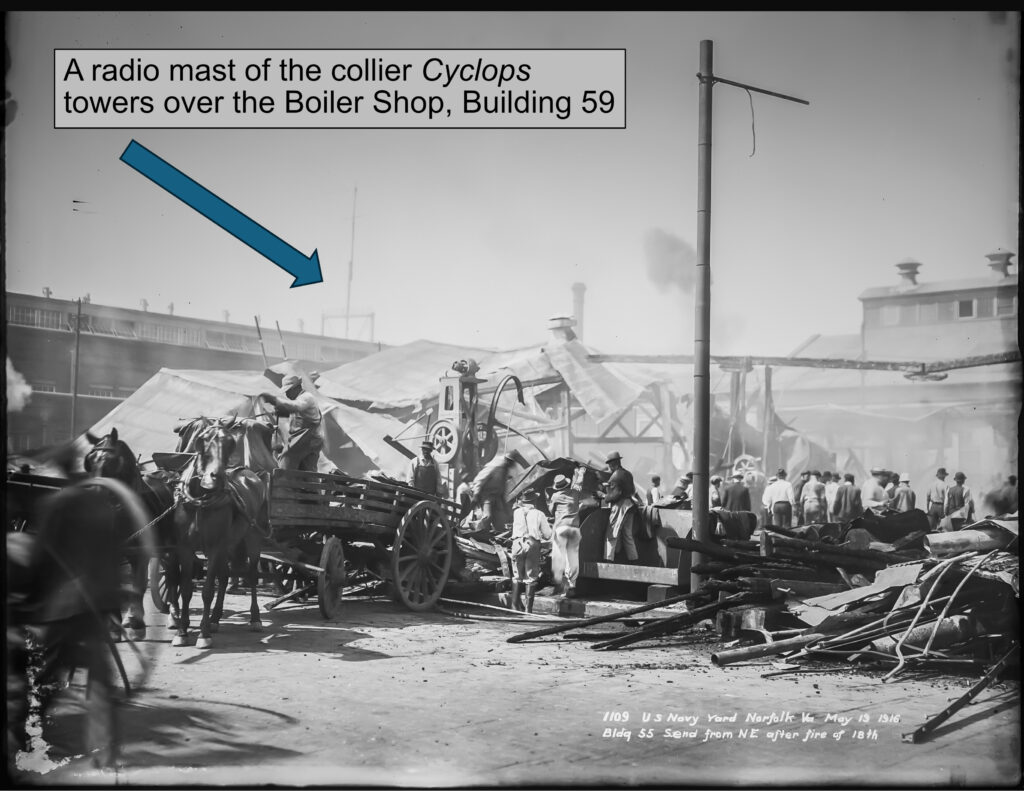

One of these photos resulted in the preparation of the article that you’re reading. It was difficult at first for me to realize that the collier Cyclops was actually in this series of unusual photographs taken at the Norfolk Navy Yard in 1916. The images on the original glass-plate negatives depict the aftermath of a disaster that took place at that navy yard. Only the top part of one of the Cyclops’ radio masts appeared in the photo as it towered over a building near the scene of the disaster. The collier’s log book entries confirmed her presence and location.

Yard workers remove debris from the remains of the shipfitter’s shop. A mast from the collier Cyclops peers over the boiler shop, building 59, to the left of the wreckage site. Debris is loaded on a horse-drawn wagon. Photo dated May 19, 1916. (NARA Record Group 181, Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments)

I should mention that after I began to prepare this article I returned to the NARA Catalog to see if there might be more views of the disaster that could be shared with you. The catalog indicated that yes, more images existed; however, they were not available. I then looked for the ones that I obtained six years earlier. Their listings appeared as before; however, they were no longer available either. (You may want to make a note for yourself, if you see it, download it. This is not the first instance where access to items in the NARA Catalog was removed.)

There’s another matter worth noting. The disaster involved the collier Cyclops and a Navy destroyer that was under construction. Neither the Cyclops nor the destroyer had much in common with each other aside from the events that took place at Norfolk in 1916.

The Disaster

The year was 1916. The war in Europe began nearly two years earlier. The collier Cyclops was in service and manned by civilians employed by the U.S. Naval Auxiliary Service. Her commanding officer was Master George W. Worley. While she was not constructed there, her ship’s home port was Norfolk. She would be placed in commission the following year.

On March 28, 1916 the collier Cyclops arrived at the Navy Yard, Norfolk, Virginia for repairs work by the yard force while berthed and in the dry dock. Most of her stay at Norfolk was uneventful.

1914 map depicts the relative locations of the collier Cyclops and building 55. (NARA Record Group 71, Records of the Bureau of Yards and Docks)

During her extended layover in port there were no coaling operations to occupy the men’s time. Instead, her civilian crew performed extensive, routine maintenance of their ship. They chipped, red-leaded and painted the ship’s sides, her smoke stacks, masts, and ventilators, the coaling booms and gear, and king posts. The men “slushed” down the coaling gear; that is, they used the grease from salt pork or boiled beef, to lubricate parts of the coaling equipment. They also chipped the deck after the starboard alley and painted the steering engine room and renewed the wheel ropes. The ship’s oil tanks were steamed out.

Mid-morning on April 28, 1916, an officer and crew of the Cyclops responded to a fire drill at the Navy Yard. That was followed by the resumption of the crew’s work about the ship for the next several days.

On May 10, 1916, the Cyclops was assisted by yard tugs from a dry dock to berth number 4 at the Navy Yard. She was all-fast in the berth at 4:50 p.m. Aside from a two-day inspection of the ship by the Supervisor of Naval Auxiliaries on May 15-16, 1916, it was maintenance as usual aboard the collier.

On May 18, 1916, at 6:05 p.m., a fire alarm in the Navy yard sounded. The nearby shipfitter’s shop, building 55, was ablaze. As soon as the fire was discovered the crews of the battleship Louisiana, the destroyers Balch and Nicholson, the collier Cyclops and the Navy Yard tugs were called to fire quarters.

Navy and civilian onlookers view the smoldering remains of the shipfitter’s shop, building 55, the day after the fire. The tall structure to the left rear is the plumber’s shop. A horse-drawn wagon is readied for removal of debris. Photo dated May 19, 1916. (NARA Record Group 181, Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments)

Second Officer Frederick J. Shaw of the collier Cyclops took a detail of men to the scene and reported to the captain of the yard. At 6:15 p.m., a hose connected to the Cyclops’ pump was run to the fire. A second line from the collier was run at 6:40 p.m. Both lines reportedly worked efficiently, maintaining 100-125 lbs. pressure. Captain Worley of the Cyclops personally directed the work of his civilian crew.

The engines of the local fire companies took positions and quickly had streams on the blaze from fire hydrants, while one fire engine was sent to the number one basin, where it pumped salt water through two lines of hose. Marines and sailors stationed at the yard assisted the regular firemen in completely surrounding the burning structure with hose streams and prevented a spread of the flames.

A detail of men from the U.S.S. Louisiana relieved the Cyclops’ men at 11:00 p.m. The hoses that streamed water to the fire maintained 120 lbs. pressure all night. The pumps were stopped at 8:15 a.m. the following day.

Yard workers clean up the remains of the shipfitter’s shop. Photo dated May 19, 1916. (NARA Record Group 181, Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments)

The fire was believed to have been caused by a short-circuited electric wire. The burned building was a one-story corrugated iron structure about 150 feet wide by 300 feet long extending between Wilkerson and Sloat Streets, on Warrington Avenue.

Naval Constructor R. M. Watt, industrial manager of the Navy Yard, placed an estimate of $100,000 damages on the fire, which he said would cause delay in the construction of the new destroyer, U.S.S. Craven.

The next day, a force of 300 men, with horse-drawn wagons, worked to clear away the wreckage of the twisted iron girders and corrugated iron shell, which was all that remained of building 55. There was a considerable salvage of the heavier tools, but all of the motors with which the machinery was operated were burned out. The more delicate tools were destroyed.

On the afternoon of May 20, 1916, with a pilot on board, the Cyclops cast off and headed to nearby coal pier no. 1 at Lamberts Point, Virginia. The collier remained in operation, to fuel the fleet, for nearly two more years. On what turned out to be her final mission, to transport a cargo of manganese ore from Brazil to the U.S., the ship was lost at sea, with all hands, in March 1918.

The shipfitter’s shop, building 55 being re-built. Photo dated November 28, 1916. (NARA Record Group 181, Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments)

The Destroyer Craven

The U.S.S. Craven (DD-70) was launched June 29, 1918 by the Norfolk Navy Yard. It was interesting to note that on the next day the Virginian Pilot newspaper published two articles, on page one, that brought the Cyclops and Craven together one more time. One described the launch of the destroyer Craven in detail. Immediately below that piece was an article titled, “Collier Cyclops is Given Up for Lost.”

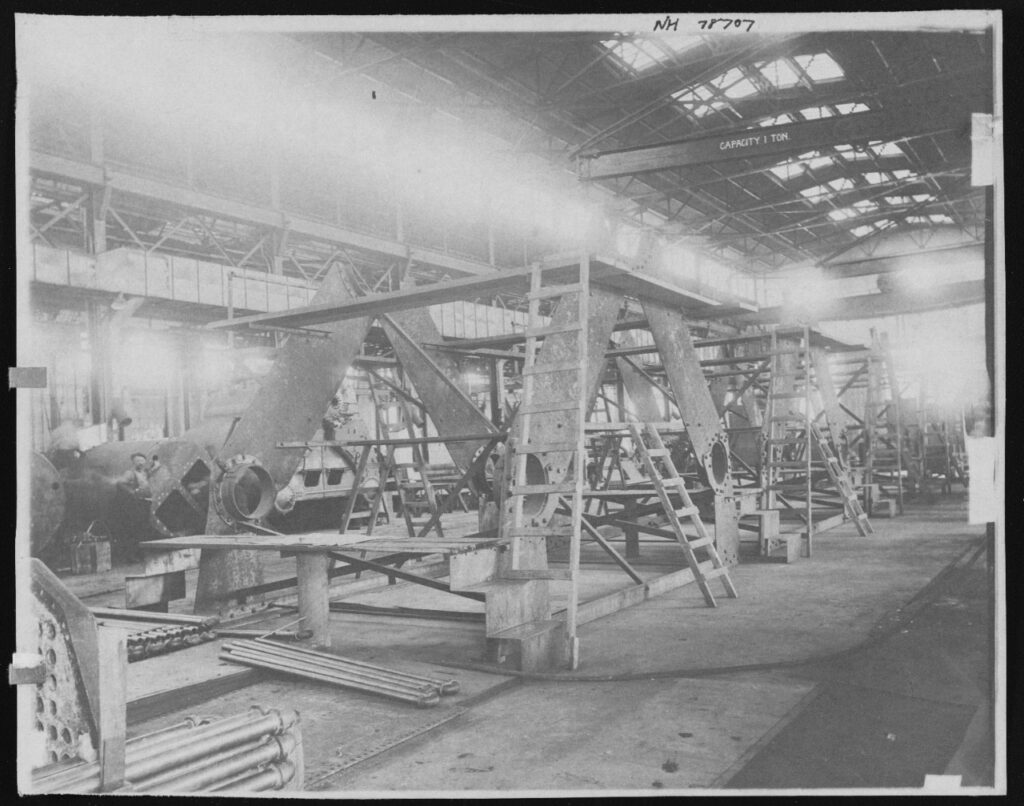

USS CRAVEN (DD-70) Construction of boilers for USS CRAVEN, at Norfolk Navy Yard, on 13 October 1917. (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. Catalog # NH 78707)

The U.S.S. Craven was commissioned on October 19, 1918. She initially operated on the U.S. east coast and in the Caribbean. On May 3, 1919 she headed from New York to Newfoundland where she served on a weather station. She was placed in reserve at Philadelphia on October 19, 1919.

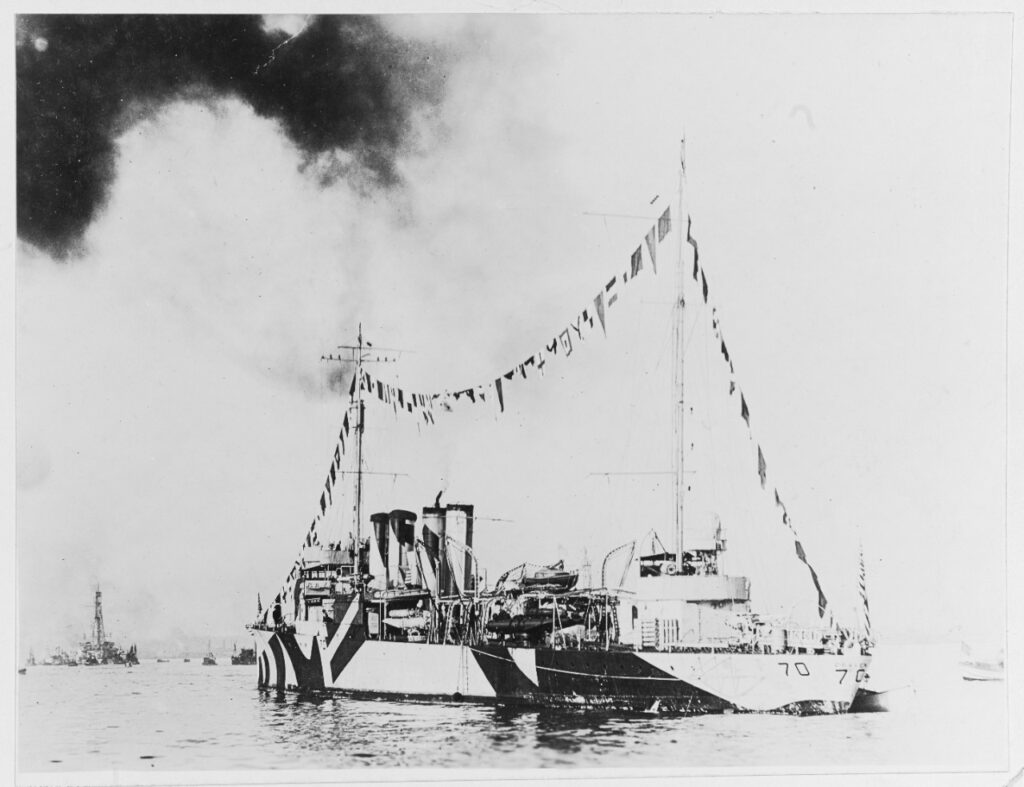

USS Craven (DD-70) Dressed with flags, circa late 1918, possibly in celebration of the 11 November 1918 Armistice. Note her dazzle camouflage. (U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph. Catalog # NH 771)

Still in reduced commission, the Craven arrived at Charleston, S.C., February 10, 1921. She transported liberty parties between Charleston and Jacksonville, Fla., and took part in the fleet maneuvers off Virginia and in Narragansett Bay. She was placed out of commission June 15, 1922. On November 12, 1939 she was renamed Conway.

Recommissioned on August 9, 1940, the Conway arrived at Halifax, Nova Scotia on October 17, 1940. She was decommissioned on October 23, 1940 and turned over to British authorities in the destroyers-for-bases deal. She was commissioned in the Royal Navy as H.M.S. Lewes the same day.

H.M.S. Lewes departed Halifax on November 1, 1940 and arrived at Belfast, Northern Ireland on November 9,1940. She was severely damaged in enemy air raids on April 21-22, 1941. She remained out of action until December 1941 when she joined the Home Fleet. In February 1942 she joined the Rosyth Escort Force and escorted convoys. On November 9-10, 1942 she engaged German E-boats which attacked her convoy. She continued operations through the remainder of World War II. On October 12, 1945 the destroyer was reported as no longer necessary to the fleet, and was ordered scrapped.

Marvin W. Barrash learned about the USS Cyclops as a child in his grandparents’ shop in Baltimore, and has been researching the fate of the vessel since 1997. He is the author of three books on the USS Cyclops mystery: U.S.S. CYCLOPS, Murder on the ABARENDA, and U.S.S. CYCLOPS Volume 2. He has appeared on a number of television programs about the USS Cyclops. His previous articles on the Doughboy Foundation website can be found here, here, here, and here.

Marvin W. Barrash learned about the USS Cyclops as a child in his grandparents’ shop in Baltimore, and has been researching the fate of the vessel since 1997. He is the author of three books on the USS Cyclops mystery: U.S.S. CYCLOPS, Murder on the ABARENDA, and U.S.S. CYCLOPS Volume 2. He has appeared on a number of television programs about the USS Cyclops. His previous articles on the Doughboy Foundation website can be found here, here, here, and here.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.