WWI Genealogy: One Family’s Research and Revelations

Published: 26 October 2022

By Chris Kolb

Special to the Doughboy Foundation web site

Since I retired, I have put a lot of effort in updating my genealogy, often wondering about many of the stories which my family members tell – how much is true and how much is an embellishment to honor my ancestors. I started researching much of the lore and wrote them down, but adding a genealogical basis for them.

In Genealogy in the Bottle: Volume 1 — Twenty-Eight Stories from Our Family Tree (2021), I tell the story of my 3rd great-grandfather, Private David Mulholland, who immigrates from Ireland in time to fight in a great Civil War. He enlisted in Company H, 97th Regiment of the Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry; engaged in trench warfare; wounded by exploding fragments; patched up; and returned to guard duty.

Undated photo of John V. Zink and his wife Anne (White) Zink (c. 1920); photo courtesy of Daniel Kolb; privately held by Daniel J Kolb in Montgomery County, Maryland.

Years later he is hospitalized as his wounds begin to take their toll. Years later he got a medical pass to visit his daughter and a new grandson he had never seen. On a train stop in Delaware, he is struck by a speeding train and dies, never meeting his eleventh grandchild, John Vincent Zink.

In Genealogy in the Bottle: Volume 2 — More Stories from Our Family Tree (2022) in two separate chapters I tell two stories related to my maternal grandfather, whom I never met, Corporal John Vincent Zink.

Mom used to tell me stories about the father whom she loved, but rarely saw. She would tell me that, “Grandpa Zink fought against the Germans in World War I. He lost two fingers when his rifle exploded and his lungs were burned with mustard gas. He was also bayoneted on the last day of the war.” Mom was really upset that he was never awarded a Purple Heart and made it her personal mission to get this awarded to him. Dad once said that the general was so annoyed at Mom’s persistence that he eventually took his own medal and “stuck it in the mail and sent it to your mother.”

So much to unpack, but I was able to cut through the lore and wrote what really happened.

The day before John turned 22 years old, the United States had officially joined the war against Germany. John Zink was a spinner for the Nice Woolen Company in Bridgeport, Pennsylvania, when he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917. He was inducted into the U.S. Army on November 2, 1917, and was assigned to Company L, 3rd Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment, United States Army. On November 21, 1917 the 30th Infantry Regiment was brought into the 3rd Army Division.

This is a government restrike of a Silver Victory Button, identical to the one given to Corporal John V. Zink, when he was honorably discharged in October 1919.

On April 2, 1918, he shipped off to France aboard the HMT (Hired Military Transport) Aquitania. The Aquitania arrived in Liverpool, England on 11 April 1918. From there the troops traveled to France.

Two months later, on June 2, 1918, John was promoted to the rank of corporal. He fought in a number of campaigns. His military record reflects that his unit fought in the following battles: The Marne, Vesle, Le Charmel, St. Mihiel, and Argonne Forest. However, there was no record of any metals, ribbons, or citations which he had received per his U.S. Army enlistment record, other than a “Silver Victory Button.” The victory button was designed to be worn on a lapel and was silver for veterans who were “wounded in action,” and bronze of all others returning home.

A new phase of the Great War began on September 26, 1918 with the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, as the American forces with the other Allies pushed through France against the German opposition. This was the largest offensive taken by the U.S. Army involving 1.2 million soldiers. Within forty-seven days over 26,000 Americans lost their lives and over 95,000 were wounded.

On October 7, 1918 orders were received by the Corps and Brigade commanders of unit and circulated. “The 3d Division was assigned the mission of cleaning up Bois de Cunel, and was ordered to capture the portion of Tranchee de la Mamelle within its zone of action. It was further ordered to occupy Cunel and Bois de la Pultiere, and to establish and maintain combat liaison with the 32d Division.” To accomplish this task, two Battalions from the 30th Infantry Regiment and two from the 38th Infantry Regiment would advance on October 9, 1918. John’s battalion was one of the two from the 30th Infantry Regiment advancing on October 9.

Soldiers unloading a patient at Field Hospital Number 28 at Varennes-en-Argonne, Meuse, France on 2 October 1918; source The United States World War I Centennial Commission www.worldwar1centennial.org ; public domain.

However, on October 7, 1918, the 6th Infantry Brigade was also directed to relieve the 5th Infantry Brigade during the night of October 7/8. The brigade was to be in place by daybreak on October 8. The 6th Infantry Brigade consisted of the 38th Infantry Regiment and the 30th Infantry Regiment (my grandfather’s regiment).

Unit reports show that the 30th and 38th Infantry regiments began relieving the 5th Infantry Brigade before midnight on October 7 and were in place by 3:30 a.m. on October 8 and began “to hold the line.” Early in the morning, the 38th Infantry Regiment encountered enemy troops holding a hill, but did not successfully repel them. Also, it was reported that one of the machine gun units was not able to disengage immediately. These factors suggest that there was an enemy presence in proximity to the position to where my grandfather’s regiment (30th Infantry Regiment) was moving on the evening of October 7 through the morning of October 8, 1918.

Also, since the attack plan called for a nineteen and one-half hour barrage against the suspected enemy positions before the advance which was planned to be launched at 8:30 a.m. on October 9, the barrage would have commenced midday on October 8, 1918.

It was at this time that John Zink was severely wounded and taken out of battle. Records obtained from Walter Reed Hospital document that John underwent surgery for a severe injury on October 8, 1918.

My grandmother and mother told the story that Grandpa Zink’s rifle had misfired and as result, he lost two of his fingers. This story became part of our family lore.

While I believe a misfiring rifle can cause a serious injury, the medical report seems to indicate that his wound was even more serious.

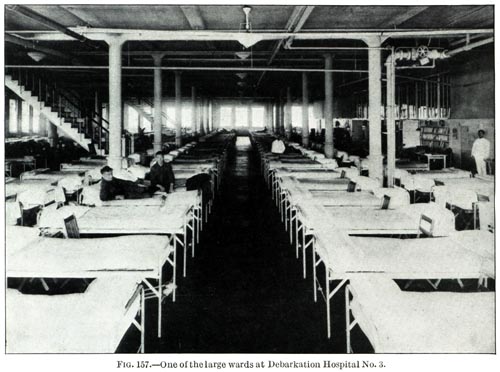

One of the large wards at Debarkation Hospital No. 3 in the Greenhut Bldg, New York City; source U.S. Army Medical Department Center of History & Heritage, https://achh.army.mil/ ; public domain.

It states that his wound was a result of a high explosive shell. My grandfather’s hand was severely injured, and a doctor had to amputate two fingers on his left hand to treat his injury.

While the specifics surrounding how his injury was sustained were not recorded, records support that he was in a hostile situation. While it is possible that he was hit by friendly-fire from the artillery barrage, I believe that is a remote possibility, as there would have been some documentation of that aberration. In my opinion, it is more likely that the two infantry regiments of the 6th Brigade were not sent to relieve units that were no longer being threatened; but that they required an active defense and John Zink was hit by pieces from a high explosive shrapnel shell or wounded from some other high explosive.

He was eventually taken to Field Hospital 28, where his surgery was performed. His battalion successfully moved forward on October 9 taking the targeted objectives; however, he was not present to witness their success.

John Zink recuperated in France for three months before he was eventually sent back to recover stateside, as it was not until January 21, 1919 that he arrived in New York aboard the USS George Washington. He was admitted to the Greenhut Building on Sixth Avenue in New York City. The Greenhut Building was the main hospital building of Debarkation Hospital Number 3, established in 1918. His medical records actually document that he was admitted to Greenhut Hospital in New York City.

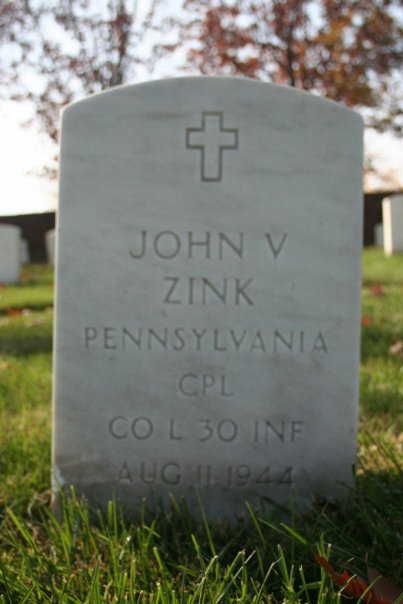

The gravestone of Corporal John Vincent Zink, CO L, 30th Infantry Regiment, US Army, in Arlington National Cemetery Section 17, Site 23169-1A; FindAGrave Memorial ID 34784620; His wife, Ann, is buried with him and her name is inscribed on the reverse of this gravestone.

Within a few weeks, John was sent to Walter Reed General Hospital in Washington, DC on February 5, 1919. John stayed at Walter Reed General Hospital until his discharge from the Army in October 29, 1919.

The next year was a happy one for my grandfather as he found the love of his life, Elizabeth “Ann” White. They married in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania on April 26, 1920 and had two girls, Mary “Shirley” Zink and my mom, Elizabeth “Jane” Zink before 1930.

After a number of years, John appeared to be showing some effects of the trauma from the war and was hospitalized at the U.S. Veteran’s Hospital at Perry Point, Maryland on July 16, 1929.

John’s death certificate shows that prior to his death, he had been diagnosed with dementia precox (a disused diagnostic term for Schizophrenia) as well as having been paranoid for over fifteen years. He never left the hospital and died on August 11, 1944 of a “coronary occlusion” due to arteriosclerosis and chronic kidney infection (Pyelonephritis).

He was buried on August 14, 1944 at Arlington National Cemetery, where I remembered my parents took us many times to visit Grandpa Zink.

My two chapters about my grandfather contain 71 endnotes supporting the facts and sources used.

For those of you who are interested in Naval trivia, I have added a few paragraphs of some interesting facts about the two ships which transported my Grandfather John Zink to and from the United States.

RMS (or HMT) Aquitania

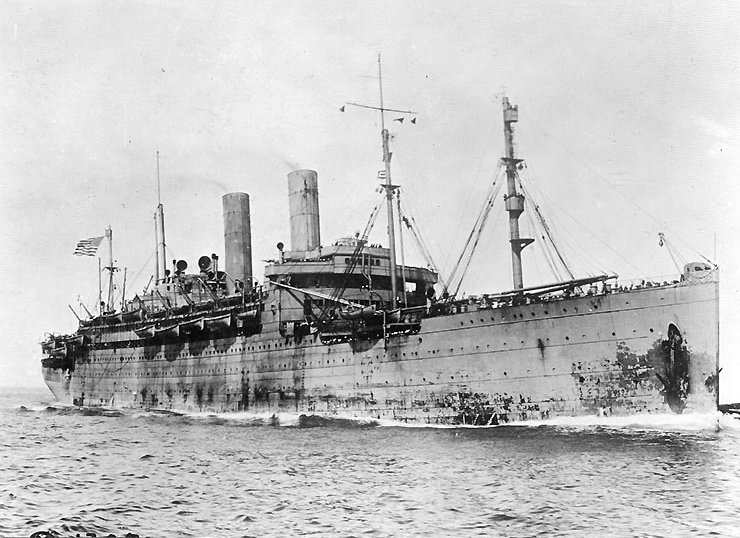

HMT Aquitania as a troop ship with naval camouflage (before 1918); Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/ ; public domain.

The HMT Aquitania was the ship which transported John Zink to Europe.

The Aquitania had an interesting history. She was built by the Cunard Lines as an ocean cruiser, and was registered as RMS Aquitania. She made her maiden voyage on May 30, 1914. She was built for speed as the third express cruiser for Cunard Lines. Incidentally, the first Cunard express cruiser was the RMS Lusitania. This is the same afore-mentioned Lusitania, which was torpedoed on May 7, 1915.

RMS Aquitania was built to carry 3,230 passengers with a crew of 972. However, on at least one occasion she carried substantially more. It has been reported that while she was a transport, she transported over 8,000 men and “transported approximately a total of 60,000 men.” Great Britain decided to use her as a troop transport ship, at which the ship’s prefix of RMS became HMT. After a few years as a troop transport ship, she was converted to a hospital ship. In 1920, more than a year after the war was over, she was returned to Cunard Lines, and resumed her service as an ocean cruiser.

USS George Washington

The USS George Washington, in United States Navy service in World War I; source https://commons.wikimedia.org ; public domain.

The USS George Washington was the ship which took John Zink back to the United States. It too has an interesting background. She was built in 1908 as an ocean liner for a Bremen Germany company and was named after George Washington, the first President of the United States. When she was built, she was the largest German-built steamship and the third-largest ship in the world. The ship was built to carry a total of 2,900 passengers, and made her maiden voyage in January 1909 to New York.

Shortly after entering the World War, the United States seized the SS George Washington and converted it to the United States troop transport ship, USS George Washington. In December 1917, she transported her first U.S. troops to Europe.

In total, she carried 48,000 passengers to France during the war, and returned 34,000 to the United States after the war had ended. The USS George Washington also carried President Woodrow Wilson to France twice for the Paris Peace Conference.

The USS George Washington was decommissioned on January 28, 1920 and handed over the United States Shipping Board (USSB), who repurposed her for transatlantic passenger and mail service.