World War I Veterans: Wounds, Opioids, and Addiction Treatment

Published: 16 November 2025

By Jordan McIntire

via the VA History website

WWI_Hospital

Wounded American servicemen at a French hospital during World War I. (Source: Library of Congress)

Often regarded as the first modern war, World War I was the first conflict to use machine guns, tanks, planes, and chemical warfare on a mass scale. This, coupled with the international nature of the conflict, led to unprecedented casualties on the battlefield. Morphine was a common drug of choice for military physicians hoping to provide pain management to injured soldiers, and it was especially effective for men who had been gassed or contracted tuberculosis.

The prescribed use of morphine during the war, however, often resulted in an addiction that followed Veterans when they returned home. While the American public generally praised World War Veterans for their service, Veteran drug addicts frequently struggled to reassimilate into a society that equated addicts with dangerous criminals. While modern medical science understands drug addiction as a chronic brain disorder, the actual and profound impact of these drugs on the brain was not widely understood in the years after World War I. At the time, addiction was instead viewed as a sign of moral and physical weakness on the part of the addict. New York Representative Lester Volk was among several advocates arguing that Veterans, since their addiction stemmed from their military service, did not deserve the “humiliation” that the public arbitrarily imposed on drug users.[1] Despite this, Veterans were not immune from the negative stigma. Contemporaneous newspaper articles referred to all addicts, Veterans or not, as “suspicious, untruthful, [and] deceptive,” and warned readers to “not keep company with any other person who is an addict…even if he is your own brother or a member of your family.”[2]

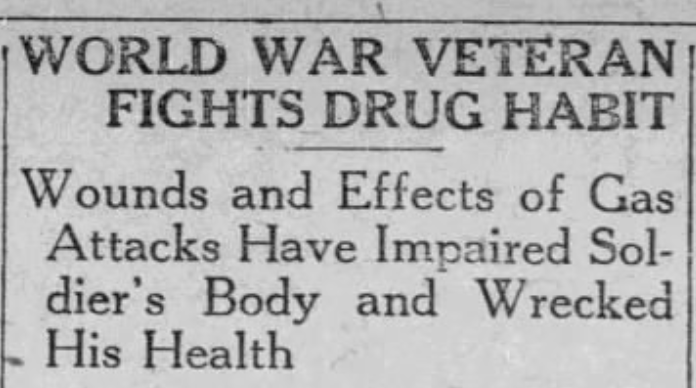

Postwar newspaper headlines, such as this one from 1922, often highlighted Veterans’ experiences with both drug addiction and the physical wounds of war.

Many Veterans sought to rid themselves of addiction in the years following World War I. While there was no guaranteed remedy for morphinism, suggested treatments ranged from a gradual reduction in morphine intake, a prescription of phenobarbital, or, simply, isolation. Some morphine addicts voluntarily committed themselves to local jails or state sanitoriums in an attempt to restrict their access to the drug. Others turned to local hospitals, which admitted hundreds of Veteran morphine addicts in the early 1920s. These hospitals often instituted the gradual withdrawal method for addiction until, in June 1921, they began administering the barbiturate phenobarbital. Veterans addicted to morphine were admitted to a closed ward where they received 2-3 daily doses of phenobarbital, which helped reduce withdrawal symptoms like restlessness, pain, and insomnia.[3] This treatment was also accompanied with warm baths, alcohol rubs, and doses of castor oil. However, J. B. Bauguss, head of the neuropsychiatric division of a Mississippi Veterans’ hospital, wrote that this treatment was not “a sure and unfailing cure for drug addiction,” and that “the majority of addicts relapse when returned to their old environment.”[4]

Major Alexander Lambert in 1918. Lambert was a recognized narcotics researcher and had extensively studied the impacts and potential treatments of morphinism. (Source: Library of Congress)

In 1921, the newly established Veterans Bureau began caring for addicted Veterans at their hospitals, many of which were transferred from the Public Health Service. These hospitals continued using the phenobarbital method to treat morphine addiction. Instances of addiction, however, continued to rise. In 1925, the American Legion announced that the Bureau Hospital in Palo Alto, California, was one of four hospitals nationwide that would be specifically tasked with caring for addicted World War Veterans. At the same time, the Bureau reached out to Dr. Alexander Lambert, a physician who had worked with the American Red Cross during World War I.[5] Lambert was a recognized narcotics researcher and had pioneered, in partnership with Charles B. Towns, the Towns-Lambert method of treating morphinism and alcoholism. Initially introduced in 1909, this method called for a gradual reduction in morphine intake combined with the administration of a mercury-based pill known as “blue mass” and a plant-based mixture of belladonna, Hyoscyamus, and zanthoxylum. Importantly, the treatment could be successfully completed in less than a month.[6] The Veterans Bureau thus began making plans for Dr. Lambert to teach this method to physicians treating Veteran drug addiction, and at least several Bureau doctors are known to have used this treatment in the late 1920s and early 1930s. [7]

Not all physicians advocated for the Towns-Lambert method, however. Dr. E. Connely, a neuropsychiatrist at the Veterans Bureau hospital in Algiers, Louisiana, published his concerns over the treatment in the Bureau’s 1926 Medical Bulletin. While he conceded that the Towns-Lambert method was often successful, he also argued that its reliance on toxic elements, namely belladonna, put patients at a severe risk of poisoning during treatment. Consequently, Connely’s proposed treatment substituted Lambert’s belladonna mixture with non-toxic Triticum.[8] According to Connely, his treatment was just as effective as the Towns-Lambert method and carried less risk to the patient. It is unclear, however, whether his treatment took hold in Veterans Bureau hospitals.

Despite evolving treatments, morphine addiction continued to plague many Veterans well after the war. In 1928, the rolls of the federal penitentiary in Atlanta listed dozens of morphine addicts. When asked how they had contracted their addiction, responses included “gassed in war,” “war wound,” “wounded Veteran,” and “wounded in France,” among other military-connected causes.[9] Even 10 years later, many Veterans still faced what was, in the words of one physician, “an affliction incomparably worse than the wounds received on the firing line.”[10]

⇒ Read the entire article on the VA History website.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.