Women Telephone Operators in World War I France

Published: 24 September 2024

By Jill Frahm

via the Center for Cryptologic History

Header Image

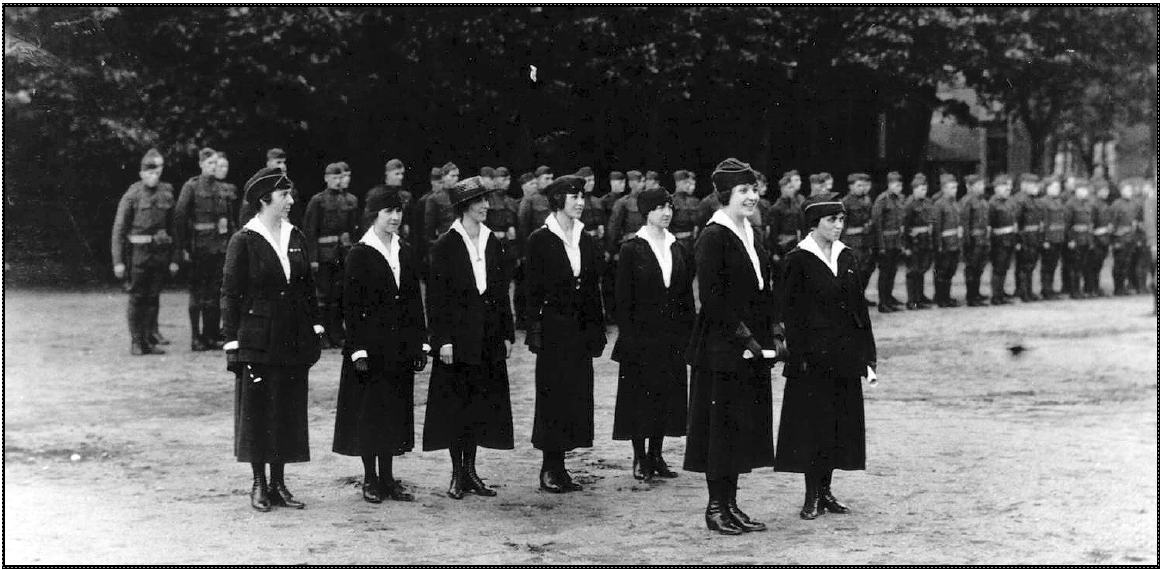

Grace Banker, front left, and some of her colleagues in the Signal Corp before receiving recognition for their work. U.S. Army, Malmstrom Air Force Base

On May 22, 1919, Grace Banker was awarded the U.S. Army’s Distinguished Service Medal for “exceptionally meritorious service to the Government in a duty of great responsibility in connection with the operations against an armed enemy of the United States.” (1) In his letter of recommendation for Banker to receive this award, Colonel Parker Hitt of the U.S. Army Signal Corps wrote, “Her untiring devotion to duty under trying conditions of service at these Headquarters has gone far to assure the success of the telephone service in the operations of the First Army against the St. Mihiel Salient and to the North of Ver- dun from September 10 to November 9, 1918.” (2)

Banker was a French-speaking telephone operator from Passaic, New Jersey. She was one of 223 operators hired by the U.S. Army to connect calls in France during World War I. (3) Originally, these operators were only expected to connect routine calls at the biggest telephone offices, far from the fighting. However, their efficiency, speed, bravery under fire, and devotion to duty so impressed their army superiors that these women became a trusted part of the military machine. They eventually advanced to the “fighting lines,” connecting even the most important calls at the First Army Headquarters near the front. Far from being insignificant, these women went on to receive many commendations for their work, including in Banker’s case, the Distinguished Service Medal. Without these women, telephone calls between major entities of the Allied effort might not have been possible.

Between the Civil War and World War I, women entered the paid civilian workforce in significant numbers, making many jobs their own, including telephone operating. By the time of World War I, they had replaced men as operators in the private sector. Although telephones and women telephone operators were an accepted part of the American business world in 1917, the U.S. Army remained unconvinced of women’s potential importance for military service. The army embraced the advantages of the telephone for military communications, but believed that enlisted men would be able to efficiently connect the calls. Further, some prominent officers continued to believe that women were emotionally unsuited to perform responsible jobs in combat situations. Thus, at the start of the war, the army did not even consider bringing female telephone operators to France.

That stance changed when enlisted men proved unable to do the job. Professional American female telephone operators were required. As a result, the operators eventually became the first American women to serve any sort of combat role with the U.S. military in an official capacity. (4) Once in that role, they proved themselves trustworthy partners to the men in battle. Yet, although they were trailblazers, the operators also remained firmly within expected gender roles. Telephone operating was “women’s work.” It was not the job the women did that proved revolutionary, but the role and location in which they did it. In the end, the bravery and excellence of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) operators’ work advanced the boundaries of acceptable wartime work for women and paved the way for the increased participation by women in World War II.

The Telephone in America

In the 20 years before World War I, the telephone was “transformed from a business tool and a luxury good to a common utility” in the United States. (5) The telephone was invented by Alexander Graham Bell in March 1876 and publicly demonstrated at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition that May. The first telephone customers initiated service the following year, and the first switchboard was operational in January 1878. Initially, the Bell Telephone Company only looked to businesses and physicians for customers, focusing on big cities at the expense of rural areas. However, after Bell’s telephone patents expired in 1893 and 1894, telephone use exploded across the United States. In the following years, Americans of all classes, all across the country, became familiar with telephones. More and more middle- and upper-class families decided to have one installed in their homes. Local shops, especially drug stores, installed telephones for the convenience of their customers, making them available to lower-income Americans. By the start of the war, the basic modern telephone system with its local and long-distance service was in place. (6) Telephones had become a common fixture in American society.

With the first switchboards came the first telephone operators. As a carryover from the related telegraph companies, boys were initially employed as switchboard workers. However, boys soon demonstrated “neither the discipline nor the deportment desired for the job.” (7) Customers complained that the boys were often rude and sometimes played jokes on them. As a solution to this problem, starting in the 1880s, telephone companies began to hire women to replace boys at the switchboards. Women were thought to be “more patient, docile, and agreeable than boys”—and, amazingly to modern readers, were cheaper to employ. (8) By 1917 operating had become a gendered occupation, with women accounting for approximately 99 percent of the more than 140,000 telephone operators in United States. (9)

Grace Banker, chief operator for the first unit of Signal Corps telephone operators to arrive in

France in March 1918. U.S. Army Women’s Museum

In principle, operating a telephone switchboard was a very simple job. An operator received a request from a customer for a connection. Using the switch- board, she merely plugged the caller’s line into the receiver’s line. But in practice, the process was far more complex. Operators had to learn to complete both local and long-distance calls, be available to assist other operators with heavy call loads, and respond appropriately to a wide variety of call situations, including delayed connections, wrong numbers, and emergency calls. Operators on large exchanges were expected to handle 250–350 calls per hour on one of three shifts: day, evening, or night. (10) Also, after connecting the calls, the operators had to disconnect the two parties as well, essentially doubling the required tasks.

Women and War

At the start of World War I, Americans were divided about what role women should play during the conflict. Many believed that women would be better off at home, safely away from the fighting. (11) However, during the American Revolution, civilian women traveled with the Continental Army and state regiments. Often the wives of soldiers, they provided support services vital to the well-being of the soldiers, including nursing, cooking, and washing. Their presence was often controversial, and they were usually not official members or employees of the armed forces. This began to change during the Civil War when the Union Army hired women to care for the sick and wounded when there were too few soldiers to do the job adequately. This lesson was forgotten until the Spanish-American War, when the lack of women nurses during the early part of the conflict cost many American lives. When epidemics of typhoid, yellow fever, and dysentery broke out, the U.S. Army had to scurry to hire professional, female nurses as contract employees to care for the sick soldiers. As a result, the U.S. Army Nurses Corps was established in 1901, and in 1916 army nurses were readily available to care for the sick and wounded during the conflict along the U.S.-Mexican border. Although the nurses lacked full army status and rank, when the United States entered World War I, they were sent to France as members of the AEF. However, further increasing the number of women workers in the war zone or around military camps seemed foolhardy to many people, especially if men could do the job. The War Department reported that “it was not yet convinced of ‘the desirability or feasibility of making this most radical departure in the conduct of our military affairs.’” (12) According to one government official, “[t]o place a small number of young women in the midst of a large population otherwise entirely of men will inevitably lead to complications that will produce a flood of adverse criticism directed against the war department.” (13) There were no plans to send any women other than nurses to France in support of the American effort during the early stages of American participation. However, necessities soon changed that plan. By the end of the conflict, women performed a variety of jobs in the war zone. They worked as nurses, occupational therapists, canteen workers, physical therapists, clerical workers, and telephone operators. It is estimated that approximately 25,000 American women worked in France during the Great War. (14) Although their contributions were significant, it would not be until World War II that women would become full members of the U.S. Army.

Bilingual Telephone Service in France

In spring 1917, as the U.S. Army began to organize the first American military contingent to go to France, it was quickly understood that it would be impossible to execute this massive operation without access to quality telephone service. The chief signal officer of the U.S. Army pointed out that “the importance of inter-communication in warfare cannot well be exaggerated. . . . Unity of command . . . can only reach its full value when the most perfect system of inter-communication is established and maintained.” (15) Telephones were the obvious answer. Major General James Harbord, chief of staff for the commander of the AEF, General John J. Pershing, recognized the need. Harbord claimed after the war that “[i]t was inevitable that the business and administrative conduct of our part of the war would be largely by telephone. … The government-owned French lines were generally so unreliable that it was necessary for the Signal Corps to put in new construction.” (16) As a result, one of the first American military units sent to France was a contingent of male telephone workers to build an American system to replace the French lines that had been shattered by three years of war. This unit included line-men, truck drivers, and other types of professional personnel employed by the Bell Telephone Company to build telephone systems in the United States. There was no thought at that point of bringing female operators to France to connect the calls. It was assumed that U.S. soldiers or local French operators could fill that role. That assumption, however, proved to be wrong.

Women operators at the switchboard in the Office of the Chief Signal Officer at the American Expeditionary Forces headquarters in Tours, France, October 17, 1918. U.S. Army Signal Museum, U.S. Army Women’s Museum

One problem was that American soldiers were not experienced operators. By 1917, telephone operating in the United States was women’s work, and few, if any, professional male operators existed. (17) Soldiers tried to serve as operators, but they were not motivated or skilled enough to work at the speed required by the army. Further, most U.S. soldiers did not speak French, which was vital since many calls went over French telephone lines. At the same time, the French operators hired by the AEF were no more successful. Many of the French women did not speak English well, and their work speed was much slower than that expected in the United States. (18) With the French telephone system chronically short of operators, these women probably had little more experience than the American soldiers. After a great deal of frustration, the U.S. Army realized that there was only one solution: bring French-speaking, professional American telephone operators to France to connect the calls.

General Pershing sent the official request for “women telephone operators speaking English and French equally well” to Washington, DC, on November 8, 1917. (19) There was apparently little resistance to his request. Within two days, the Office of the Chief Signal Officer was placing newspaper advertisements for operators in promising cities around the country. The New Orleans Times-Picayune, for example, was asked to give “the greatest publicity” to the Signal Corps’ “urgent need, for immediate service in France, of one hundred telephone operators who must be able to speak French and English.” (20) Thousands eagerly applied for this opportunity to go “over there,” and the AEF asked the American Telephone and Telegraph Company to sift through the applications and find the most qualified women for this work. The first operators were officially appointed in January 1918. The first contingent arrived in France in March 1918, and U.S. military personnel began to see improvement in the telephone service almost immediately, both in speed and efficiency. “These girls are going to astound the people over there by their efficiency,” predicted Captain E. J. Wesson, who recruited the women operators. “In Paris, it takes from 40 to 60 seconds to complete one call. Our girls are equipped to handle 300 calls in an hour.” (21) According to Colonel Parker Hitt, chief signal officer, First Army, “The remarkable change in the character and service at the General Headquarters and other points” in France was the result of the American women taking over. (22) One operator later recalled, “Oftentimes during the early days, after saying, ‘number please,’ there would be a silence broken by an awed, ‘Oh!’ Sometimes it would be, ‘Thank heaven you’re here at last!’ One man called for the American ambassador and added, ‘God bless you!’” (23)

Operators were assigned to large offices (toll centers) with the heaviest traffic, where their expertise was most needed. (24) The first group of operators was divided between telephone offices in Tours, Chaumont, and Paris. As the American telephone network in France continued to expand, additional telephone offices that also used the American operators were established in other cities, including Bordeaux, Le Havre, Neuf Chateau, and Toul. By the time the war ended in November 1918, a total of 223 American female operators had been sent to France and were connecting calls all across the country. (25)

Bravery under Fire

Beyond connecting calls in safe offices, some of these women ended up in dangerous situations and proved themselves reliable cogs in the military machine. The first contingent of operators sent to France was the first to be tested under fire. They arrived in Paris late on March 24, 1918, after a grueling trip across France, where their train had been forced to stop frequently to avoid German air raids. After settling into bed at the Hotel Ferras, where they were to be living, the operators were awakened by the sound of air raid sirens. They dashed to the safety of the basement bomb shelter. Cordelia Dupuis later recalled that they slid down the banisters in their nightgowns. (26) Cots had been placed down there for them, and many of the operators soon went back to sleep, too tired to do anything else. They did not take the bombing too seriously until the next morning when they saw the resulting damage. Within two days, all but ten of the original group were sent to offices outside of Paris. For those who stayed, the danger remained. (27)

Frequent bombings continued in Paris, as the ten operators bravely connected the calls at the American telephone exchange housed at the Élysée Palace Hotel. One of their most memorable adventures was provided by the German long-range gun “Big Bertha.” As one operator later recalled,

For several days on end she would visit us punctually every fifteen minutes. Places were struck all around us, but fortunately neither our office . . . nor our house . . . was touched. …At lunchtime, the operators would wait for a report from the big gun, and would hurry home as fast as they could, arriving there just ahead of Bertha’s next greeting. (28)

The German bombings of Paris continued into June. During one particularly dangerous evening, operators were asked to leave their positions to seek shelter. Suddenly, a window in the telephone office was smashed by a shell fragment. In spite of the ensuing confusion, the women calmly remained at their posts while the men sought cover. “We will stay until the last man leaves,” they said, and they were among the last to go to safety. This event was not lost on military officials. As one officer later reported, “This is the fibre [sic] of the enlisted sisters of our fighting men.” (29)

However, this was not the end of the bombings. As Parisians left their city in increasing numbers, the U.S. Army began to formulate plans to evacuate the operators if the Germans got too close to Paris. The operators were told “to have their bags packed and be within calling distance at all times.” (30) Army trucks were kept ready to evacuate the women. When the operators found out about these preparations, they were furious. As one operator put it,

When it was rumoured [sic] that there was a possibility of our having to leave, there was hearty protestation. The telephone business, we felt, had become well-nigh unmanageable on account of the drive going on, and it seemed to us that to put inexperienced boys in our places might prove disastrous. (31)

After listening to their arguments, the AEF postponed the operators’ evacuation for one more day. Fortunately for the operators, the Germans were pushed back the next day, and the operators never had to leave their positions.

Operators of the “Fighting Lines”

Over the summer of 1918, the operators’ responsibilities expanded and their reputations grew. As well as connecting calls on American lines and between French and American lines, the operators were “translating and routing extremely sensitive information regarding troop movements, supply, logistics, and ammunition between major allied commanders.” (32) According to operator Louise Barbour, “When Pershing can’t talk to Col. House or Lloyd George unless you make the connection, you naturally feel that you are helping a bit.” (33) In spite of the fact that new operators continued to arrive from the United States, there were never enough to completely replace the men. One operator recalled that women were on duty during the day when traffic was the heaviest, and men worked at night when the traffic was slow. (34) Some women worked at offices where codes and cover terms were used. Their work became more and more important to the Allied effort. It was even rumored that French commander Ferdinand Foch was so impressed by the American telephone service that he would drive miles out of his way to use an American telephone. (35)

The first unit of Signal Corps telephone operators to arrive in France in March 1918 poses with Signal Corps soldiers. The March 29 edition of the Stars and Stripes newspaper said: “They arrived just the other day, and like everything else that’s new and interesting in the Army—yes, they’re in it too—they were lined up before a Signal Corps camera and shot. Grouped about the base of a statue in a little Paris square, they presented a pleasing sight. (American girls always do.)” US Army Women’s Museum

August 1918, as the American forces prepared to take part in the major offensive near St. Mihiel, Colonel Hitt was determined to bring women operators along to support communications at General Pershing’s headquarters near the front lines. Hitt had been a strong supporter of bringing the operators to France from the start and, like everyone else, was impressed by their work. He wrote the Chief Signal Office, AEF, that “in order to obtain maximum efficiency of the telephone central … I desire to use women operators.” (36) His request was approved, and a call went out for volunteers among the American female operators in France. Almost every operator wanted to go; however, only six were selected: Grace Banker, Suzanne Prevot, Esther Fresnel, Helen Hill, Bertha Hunt, and Marie Lange. Once at First Army Head- quarters, the women worked in shifts—six hours on and six hours off—running the switchboards through the battle. Initially the women were supposed to only connect the lines handling routine calls, with male operators handling the “fighting lines”—those lines between officers at the front. According to operator Bertha Hunt, “Every order for an infantry advance, a barrage preparatory to the taking of a new objective, and, in fact, for every troop movement, came over these ‘fighting lines.’” (37) The fighting lines had both French- and English-speaking male operators. When a call came in, a male operator would pick it up, and if he could not understand the language, he would hand it off to another male operator who could. This system proved highly inefficient, especially with bilingual female operators seated nearby. With their language skills and efficiency, the women soon replaced the men on these key lines.

Further, the women could also translate messages between French and American officers and might even relay messages from one unit to another if direct connections were impossible. The work at First Army Headquarters required the use of many code words and cover terms. For example, “Toul” might be “Podunk” one day and “Wabash” another. The 4th Corps was, at one point, “Nemo.” Years later, Grace Banker remembered that to the uninitiated, messages sounded like something out of the mad tea party in Alice in Wonderland, especially on the day when one operator had to explain to a caller why she could not get “Jam.” (38) The operators remained with the First Army through the remainder of the war, although additional operators later joined them when the workload grew too much for the original group.

Not surprisingly, these operators were very dedicated to their duty. When the telephone office caught fire during one of the First Army operations, the operators refused to leave their positions up until they were threatened with court martial. An hour later, when the building was declared safe to enter, the operators were back at their switchboards. Although two-thirds of the wires had been destroyed, the women continued to connect calls with the lines that remained. The operators even impressed veteran war correspondent Don Martin of the New York Herald, who claimed that the efficiency of the American Army switchboard was

as complete as that of a financial institution in Wall Street. There is no delay. In dozens of instances during the severest fighting, in which officers called up headquarters miles away, they got a reply immediately—never a delay. The efficiency of American business methods, which it was hoped would be gradually developed in the war machine, even in the midst of such excitement, has been realized, and that is one of the reasons why the operations went through so quickly and cleanly. (39)

Conclusion

Female telephone operators became an important part of the American effort in France during World War I. They made telephone calls possible, even during battle. They served bravely under fire and were dedicated to their duty. According to Parker Hitt, the success of First Army communications through the last battles of the war was largely due to the abilities of the operators. (40) These women had skills that were not found anywhere else. Had bilingual male operators been available, the army would have used them. However they were not, and time and time again, the women proved that they could do the job far better than the men, so much so that AEF communications would probably have suffered without them. And as noted, fast, efficient communications are vital in modern warfare. The women repeatedly proved that they were professional and dedicated, even under fire. They remained calm, stayed at their posts even in dangerous situations, and continued connecting the calls, particularly in Paris and with the First Army. The praise and recognition in operator Marie Belanger’s commendation could have applied to all the operators: “You personally have been of material assistance in proving the success of the experiment of utilizing skilled telephone women with the Army at war.” (41)

Although operating a switchboard in a war zone challenged the idea of the proper role of women during wartime, it should also be noted that the work itself did not otherwise challenge gender roles. The public generally believed that telephone operators, like nurses, were supposed to be female and that women performed that job better than men (a popular perception was that women’s fingers were nimbler than men’s, for example). Men who were assigned to serve as telephone operators were resistant to the job and often fought to be reassigned. They would not and could not fill the role as well as the women. In the United States almost all telephone operators were women, and men were accustomed to women filling this role in the business world. The fact that a female voice greeted them when making a telephone call was an ordinary occurrence. When the army needed skilled, professional operators, it naturally turned to women, following the prevailing customs of the day.

At the same time, the operators were trailblazers for women in the military. They were the first to serve in any sort of combat role on a regular basis. Certainly women had served in limited combat roles before, but never in any sort of official capacity with so much responsibility. The AEF telephone operators thus established a precedent and paved the way for the enlistment of women during World War II.

At the same time, the operators were trailblazers for women in the military. They were the first to serve in any sort of combat role on a regular basis. Certainly women had served in limited combat roles before, but never in any sort of official capacity with so much responsibility. The AEF telephone operators thus established a precedent and paved the way for the enlistment of women during World War II.

The telephone operators also helped pave the way for women to become full members of the U.S. Army. The operators were contract employees. Unfortunately, due to army mismanagement, the women were led to believe that they were regular members of the army until after the war. They were stunned to find out that after their outstanding work and dedication, they would be denied recognition as veterans. The operators, led by Merle Egan Anderson, fought for decades to right this injustice. The surviving women finally received their official army discharges in 1979. It was this ongoing battle that helped convince some members of Congress, like Edith Nourse Rogers (R-MA), that women should be made regular members of the U.S. Army.

In the years between the two world wars, military and government leaders debated the feasibility of forming a women’s service organization attached to the army. Although no plan was in place when World War II started in Europe, it had become clear that women would be necessary for successful military operations in any future war. General George C. Marshall, a supporter of a woman’s corps, pointed out in summer 1941 that it was “foolish and uneconomical” to train men to do jobs that women typically performed, and performed well, in civilian life. For example, Marshall continued, “the Army’s telephone service [has] always had a reputation for being bad in spite of superior equipment, and women could . . . end all that.” (42) When the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was formed in May 1942, telephone operating was one of the first jobs authorized for the women. Although the Signal Corps was hesitant to employ WAACs because of concerns about their “auxiliary” status, when the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) was established in 1943 making women full members of the army, it was the first of the Army Service Forces’ agencies to request these women. Historian Mattie Treadwell credits the excellent work of the World War I operators for inspiring this enthusiasm. (43) WAC telephone operators went on to serve in all the major theaters of the war as well as at the various conferences held by the Allied leaders. World War I success helped pave the way for the use of operators and other women workers in positions of responsibility during World War II.

The female telephone operators who served in France during World War I made fast, efficient telephone communications possible. Without their work, information vital to the success of battle might not have made it to the right place on time. Their professionalism, dedication to duty, and bravery showed that women could be an important part of the American military and provide vital support to American military operations. As operator Oleda Joure put it, “A fast and effective communications system was of paramount importance in the war effort for victory, and I feel our telephone operators contributed immeasurably toward this end.” (44)

Jill Frahm teaches history at Dakota County Technical College in Rosemount, Minnesota. She holds a B.A. and M.A. in history from the University of Maryland and a Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota. She is a former senior historian at the Center for Cryptologic History, where her research focused on women in cryptology and SIGINT during the Korean War. Her current research focuses on unconventional women during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. She would like to thank Benjamin Guterman and William Williams for their assistance with this article.

Notes

- “Distinguished Service Medal,” Military Personnel (201) Folder of Grace Banker; National Personnel Records Center, St. Louis (hereinafter NPRC).

- “Recommendation for Distinguished Service Med- al for Chief Operator Grace Banker, Signal Corps,” Personnel (201) Folder of Grace Banker; NPRC.

- The AEF telephone operators in France are often referred to as the “Hello Girls.” In the early 20th century, “hello girl” was common slang for a telephone operator. Although it was used in connection with the AEF operators in the press, it was never used in official army documents and rarely used by the women themselves. I chose to follow the official records and do not use the term in this paper.

- Although nurses were the first women in the U.S. military and made very significant contributions, they were not involved with the actual fighting. The operators were.

- Claude S. Fisher, America Calling: A Social History of the Telephone to 1940 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 50.

- Ibid., 42.

- Kenneth Lipartito, “When Women Were Switches: Technology, Work, and Gender in the Tele- phone Industry, 1890–1920,” American Historical Review 99, no. 4 (October 1994): 1082.

- Maurine Weiner Greenwald, Women, War, and Work: The Impact of World War I on Women Workers in the United States (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1990), 190.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 199.

- Susan Zeiger, In Uncle Sam’s Service, Women Workers with the American Expeditionary Force (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999), 17.

- As quoted in Mattie E. Treadwell, United States Army in World War II Special Studies: The Women’s Army Corps (Washington, DC: Department of the Army, 1954), 7.

- “A Study of the Service of Woman Telephone Switchboard Operators of the A.E.F.,” 231.3 – (WW) Overseas Telephone Operators; Study Made by War Plans and Training; Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, Record Group (RG) 111, Box 400, Entry 45; National Archives and Records Administration at College Park, MD (hereinafter NACP), 4.

- Dorothy and Carl J. Schneider, Into the Breach: American Women Overseas in World War I (New York: Viking, 1991), 11–12.

- As quoted in A. Lincoln Lavine, Circuits of Victory (Garden City, NJ: Country Life Press, 1921), xx.

- As quoted in “The Army’s Forgotten Women,” World War I Survey, Archives, U.S. Army Military Institute, Carlisle Barracks, PA, 1.

- Lipartito, “When Women Were Switches,” 1082; Michèle Martin, “Feminisation of the Labor Process in the Communication Industry: The Case of the Telephone Operators, 1876–1904,” Labor/ Le Travail 22 (Fall 1988): 139.

- “Extract From Narrative of Captain A. L. Hart, S.C., Assistant to Signal Officer in Paris,” Study Made by War Plans and Training Division; 231.3 Telephone Operator (Overseas) Legislation and Status – 231.4 Draftsmen; Office of the Chief Signal Corps Correspondence, 1917–1940, RG 111; NACP, 1350.

- Cablegram titled “Headquarters American Expeditionary Forces, Office of the Chief Signal Officer,” Study Made by War Plans and Training Division; 231.3 Telephone Operator (Overseas) Legislation and Status – 231.4 Draftsmen; Office of the Chief Signal Corps Correspondence, 1917–1940, RG 111; NACP, 1331.

- Office of the Chief Signal Officer to the Editor, New Orleans Times Picayune, New Orleans, LA, November 10, 1917; Office of the Chief Signal Corps Officer Correspondence, Box 396, Entry 45, RG 111, NACP.

- “Girls Do Good Work,” The Bourbon News (Paris, KY), July 16, 1918.

- Report of Chief Signal Officer (Washington, DC, 1919), 540.

- Lavine, Circuits of Victory, 279.

- Report of Chief Signal Officer, 540.

- A significant number of operators were also in training in the United States when the war ended and were discharged shortly after the armistice. The army hired a total of 377 female telephone operators.

- Lettie Gavin, American Women in World War I (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 1999), 81.

- Lavine, Circuits of Victory, 277–278.

- Ibid., 278.

- Isaac F. Marcosson, S.O.S. America’s Miracle in France (New York: John Lane, 1919), 116.

- Lavine, Circuits of Victory, 359.

- Ibid.

- Carla Wiegers, “The Hello Girls of the Great War,” The Banner XIV, no. 1 (Winter 2000): 5.

- Louise Barbour to “Darling Mother,” November 24, 1918. MC 219, folder 3: Louise Barbour Papers, 1917–1939; Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

- Michelle A. Christides, “Women Veterans of the Great War: Oral Histories Collected by Michelle Christides,” Minerva: Quarterly Report on Women and the Military (Summer 1985): 109.

- Wiegers, “The Hello Girls of the Great War,” 5.

- Lavine, Circuits of Victory, 491.

- As quoted in Lavine, Circuits of Victory, 565.

- Grace Banker, “I was a ‘Hello Girl,’” Yankee Magazine (March 1974): 71.

- Lavine, Circuits of Victory, 490–1.

- “A Study of the Service of Woman Telephone Switchboard Operators of the A.E.F.,” 231.3, RG 111, NACP, 26.

- Personnel (201) folder of Marie Belanger; NPRC.

- Treadwell, United States Army in World War II Special Studies, 20.

- Ibid., 309.

- Christides, “Women Veterans of the Great War,” 112.

♦ Center for Cryptologic History, 2016 ♦

Read and download the entire article on the defense.gov website here:

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.