Winterberg – How a Long-Forgotten World War I Tragedy Ended Up in My Book

Published: 28 December 2025

By David Wessel

Special to the Doughboy Foundation website

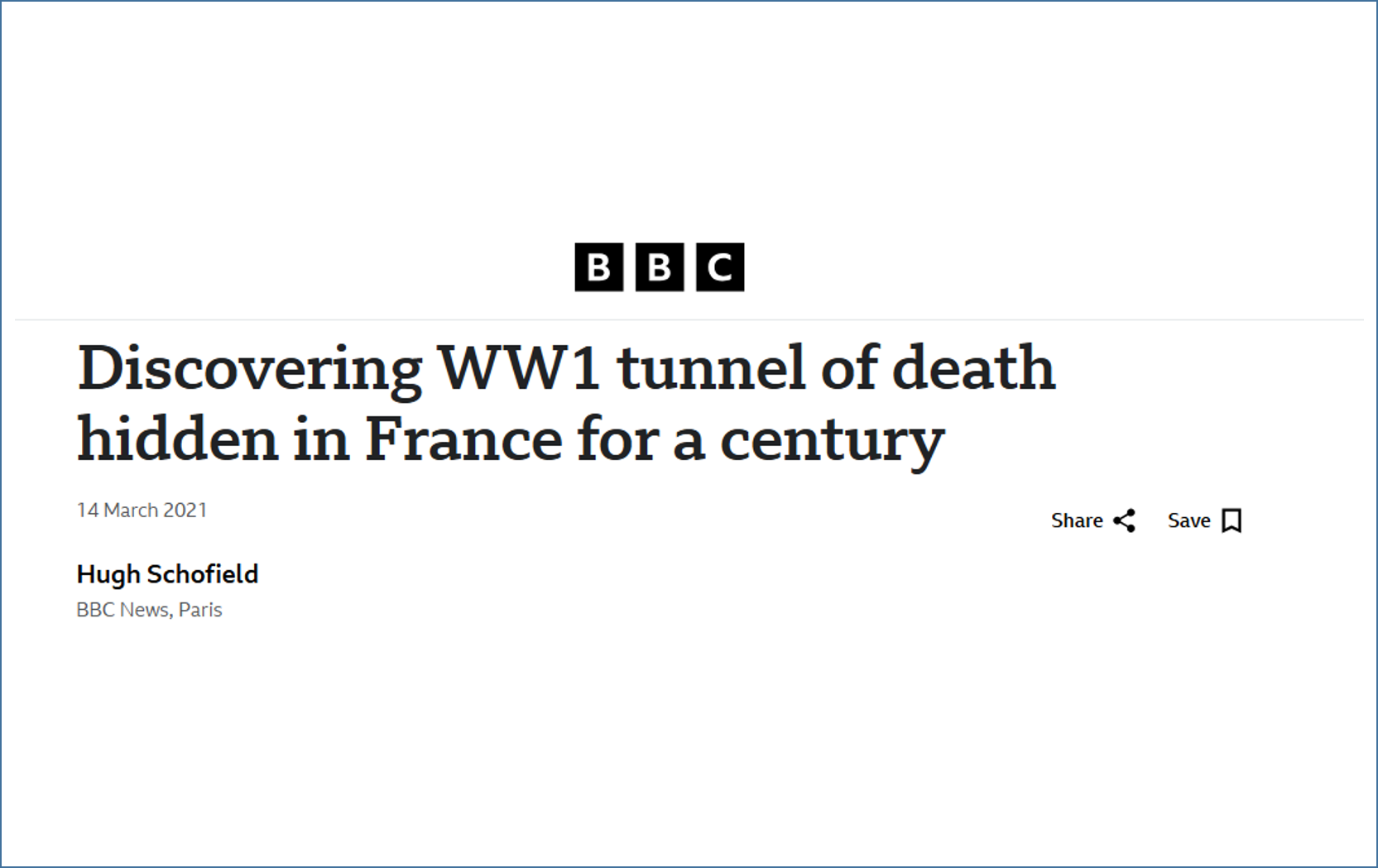

BBC screenshot framed

This is a screen-shot of the BBC article that drew my wife’s attention.

I recall the moment, late one afternoon in the winter of 2021, that my wife brought “The Tunnel of Death” to my attention. I had been at my desk for several hours, working on the first draft of a historical novel, when she interrupted my concentration to show me an article she’d just read on her laptop. She wondered if the story, on the BBC website, might be something to include in the novel. She knew I had been working on a chapter relating the miseries my German grandfather had experienced fighting in the trenches of the First World War.

The headline read: Discovering WW1 Tunnel of Death Hidden in France for a Century.[i] (BBC News; 14 March 2021; Hugh Schofield; BBC News, Paris) The first paragraph told me that a father-son team of historians had discovered the entrance to a long-forgotten tunnel in the woods near the city of Reims, where over 270 German soldiers had suffered most horrific deaths. My first thought was that this may or may not fit into my book, but was certainly an interesting story in and of itself.

In the next second, I changed my mind. There were photographs of three soldiers who had died in the tunnel. One of them leapt off the screen as I read the name: Wessel, Albert, Non-Commissioned Officer. This poor soul and I shared a common family name! Because it was printed in an old-style, German gothic font and used the German esszett symbol rather than two s-letters, my wife had not caught that part.

Photographs from the BBC article of three soldiers who had died in the Winterberg tunnel. One of them is named Albert Wessel.

So, yes, I knew right away, I must include the story of the Winterberg Tunnel in my novel. I did not know the names of all my grandfather’s six brothers, but decided then and there that Albert might very well have been one of them. And since I was writing historical fiction, inspired by true events, Albert became part of my family and the family-based novel I was writing. To make sure I got the story right, I just had to spend some time researching the history behind the Tunnel of Death.

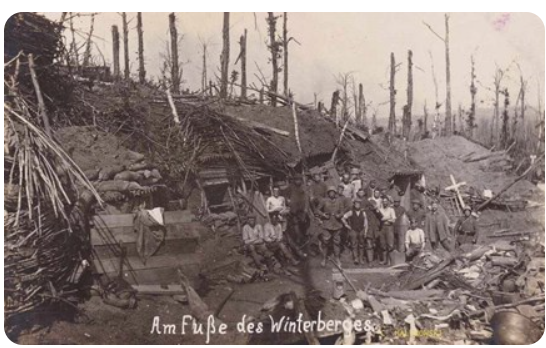

It seems the German army had dug in near a ridge outside of Reims that had for years been quarried for stone, leaving a labyrinth of caves and tunnels. They used one such tunnel, running almost 1000 feet long under a hill they called Winterberg. to get supplies to the front-line trenches without going up and then back down the steep terrain. It was a faster, safer way of transporting food and munitions – and provided the German army with a cool, dry space for their stores of weapons and explosives.

But one day in May 1917 the French launched an artillery bombardment and succeeded in sealing first one end, and then the other, of the tunnel – with a regiment of German soldiers still inside. Some of them fled the explosions at the two entrances, running into toxic fumes deeper inside the tunnel. Some stayed near the entrances, praying for rescue. Three lucky men were indeed rescued, but heavy shelling and a French attack on the hill, prevented the others from being saved; they would die of poison gas, suffocation and/or starvation. The French troops took the ridge and, concerned with other matters, made no attempt to rescue members of the enemy forces. By the time the Germans later reclaimed Winterberg, it was too late to look for survivors or recover the bodies of those who had perished. So the tunnel remained sealed.

Photo of an entrance to the Winterberg Tunnel. A Fench bombardment in May 1917 sealed both ends of the tunnel with a regiment of German soldiers still inside.

I incorporated the Tunnel of Death into my novel in the form of a letter written by one of the Winterberg survivors, sending word about the event to Albert’s parents. It is all quite fictitious, but reflects something that very well could have happened.

The letter reads:

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Wessel,

I am so sorry, so very sorry to write this letter, but I must tell you that I have served with Albert for the last six months and have come to think of him as my brother. He has helped me deal with so many troubles here on the front and I do not know if or how I would have survived without him.

But I am writing to tell you that he has been killed here in Reims, in a most heroic manner. I cannot be sure if the Reich’s Army will provide you with any details, but since I was there with him, I feel if is my duty to tell you what has happened. One day, when this is all over, I will visit to provide more details. But for now, let me tell you that your son save my life and I will forever keep him in my heart.

We had been using an underground passage to get supplies from our camp out to the men in the trenches, rather than go up and over a steep hillock called Winterberg. I made many trips with Albert and our fellow supply-men through the Winterberg Tunnel. But on our last trip, 4 May, the French had an observation balloon above the hill and managed to launch an aerial bombardment on both ends of the passage. Usually their bombs fell well off target. But this day they were formidably accurate.

One shell, fired from a nearby cannon, hit an ammunition supply we had staged at the eastern end of the tunnel. A thick cloud of smoke and fumes came rushing in, just after Albert and I had entered. We scurried like crazy to get back to the western end so we could exit. As we got to the opening we heard the screaming whistle of incoming artillery. Your son gave me a push from behind – just as a bomb exploded on the hillside above us. That push propelled me through the exit, but the bomb started a landslide that sealed the tunnel closed.

Several of us dug, as long and hard as we were able, to clear out the entrance, using our helmets, our hands, tree branches, anything we could find. We knew hundreds of men, Albert included, were still inside. We dug furiously; but after about twenty minutes, French troops came over the ridge and we were forced to retreat. The enemy troops did not know there were men trapped in the passage and probably would not have cared even if they did.

And so the battle for Winterberg was lost – and so too was my colleague, my friend, the bravest man I have ever known; your son – Albert.

Yours most sadly … Corporal Josef Romelzek

In my book, Choosing Sides, the letter is used fictitiously. There was no Corporal Romelzek, there was no letter home to Albert’s parents, and there is no proof that the Albert Wessel who died in the Tunnel of Death was in fact my grandfather’s brother. But I have used the letter as a vehicle to present an historical event in an honest fashion, hoping to portray to the reader a sense of what it felt like to live through a terrible event in world history. The book is focused on a family (my own) torn apart by Hitler’s Germany. It features my grandfather, who became a pacifist after the First World War and subsequently took his family out of Germany before the start of the Second. And it features my father, who at the age of eighteen was a German citizen living in the United States when FDR declared that we were entering the fray. My dad was faced with returning to Germany to fight in the Wehrmacht or joining the U.S. Army, which would give him American citizenship. He was an enemy alien living on American soil and found himself Choosing Sides.

In my book, Choosing Sides, the letter is used fictitiously. There was no Corporal Romelzek, there was no letter home to Albert’s parents, and there is no proof that the Albert Wessel who died in the Tunnel of Death was in fact my grandfather’s brother. But I have used the letter as a vehicle to present an historical event in an honest fashion, hoping to portray to the reader a sense of what it felt like to live through a terrible event in world history. The book is focused on a family (my own) torn apart by Hitler’s Germany. It features my grandfather, who became a pacifist after the First World War and subsequently took his family out of Germany before the start of the Second. And it features my father, who at the age of eighteen was a German citizen living in the United States when FDR declared that we were entering the fray. My dad was faced with returning to Germany to fight in the Wehrmacht or joining the U.S. Army, which would give him American citizenship. He was an enemy alien living on American soil and found himself Choosing Sides.

But, getting back to the Tunnel of Death and the discovery of its location. After World War I, the area around Winterberg was allowed to return to nature. It has become a popular place for nature hikes and dog walking but is undeveloped. The exact location of the tunnel entrances was unknown until 2009, when Alain Malinowski, who was obsessed with finding it, discovered a map of its location. He and his son, Pierre, then spent another decade searching for one of its entrances. They knew one end was in France and the other in Germany but receive no cooperation in their search efforts from either country.

Frustrated by this, in January 2020 Malinowski excavated a suspected French site, using a crane on public land, despite the potential legal issues that might follow. There he found a few artifacts that provided evidence he had located the correct site – and again waited for action on the part of the French government. Months later, again frustrated by the slowness of any official response, he went public with the news of his discovery. He told the French newspaper, LeMonde, about his find, sparking an international debate on what should be done.

Finally, in 2021 French and German organizations decided to open up the tunnel with the idea of giving a proper burial to the soldiers who had died over 100 years earlier. In March of that year, the bodies of some of those unfortunate German World War I soldiers were found; nine of them identified by their dog-tags as being part of the 111th Regiment. Further efforts to excavate the site and relocate the remains have proven very difficult. This is in part because the site is situated in a nature reserve, partly because the ground is very sandy, and partly because the land was still contaminated with ammunition that might still be live.

In 2022 a Franco-German team managed to see as far as 210 feet (64 meters) down the tunnel. They were able to retrieve some artifacts, but reported they found no other remains. In 2023 it was decided that the peace those soldiers had in death was not to be disturbed by further efforts to relocate remains. The site was declared a war memorial in February of that year with representatives of both France and Germany emphasizing the importance of this French-German cooperation. They expressed hope the memorial could be inaugurated in 2024; but a recent Google search revealed that the Winterberg Tunnel War Memorial has not yet been built.

In the meantime, it is hoped that the men who perished in the Winterberg Tunnel, including my adopted great-uncle Albert, are resting in peace.

[i] BBC; 14 March 2021; Hugh Scofield, BBC News – Paris; accessed 26 December 2025; https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-56370510

David K. Wessel is a retired U.S. diplomat and lifelong amateur historian with an interest in German history between the two world wars. He has published non-fiction articles in American Historical Association’s Perspective magazine as well as the Foreign Service Journal. His first book, Choosing Sides, is a work of historical fiction that relates world events to his own family’s history and portrays how ordinary families dealt with the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party in the 1920s and 30s.

David K. Wessel is a retired U.S. diplomat and lifelong amateur historian with an interest in German history between the two world wars. He has published non-fiction articles in American Historical Association’s Perspective magazine as well as the Foreign Service Journal. His first book, Choosing Sides, is a work of historical fiction that relates world events to his own family’s history and portrays how ordinary families dealt with the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party in the 1920s and 30s.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.