Why America Builds Monuments

Published: 18 April 2025

By Sabin Howard

via the Modern Age website

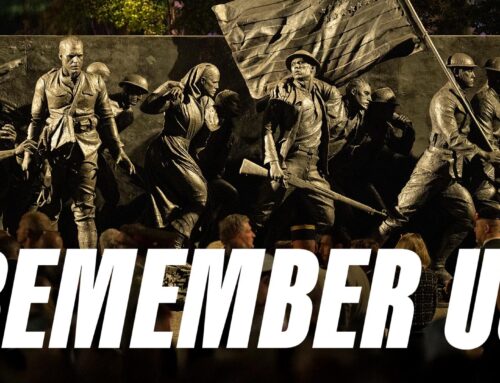

wwi-again-e1744923005927

Detail from Sabin Howard's sculpture at The National World War I Memorial in Washington, D.C. (National Park Service)

Throughout the history of the United States, when our nation faltered—when wounds ran deep and identities fractured—Americans did not retreat into silence. We built monuments: not merely to commemorate, but to repair and restore our American spirit.

After the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln stood at Gettysburg not just to consecrate the dead but to awaken the living. His words, “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom,” redefined American unity. That moment was not about closure; it was about becoming whole again.

Decades later, Theodore Roosevelt commissioned Mount Rushmore, carving into the granite of South Dakota the faces of four presidents who had shaped a fledgling republic into a confident nation. Mount Rushmore was not nostalgia. It was ambition etched in stone—vast, defiant, hopeful.

Then came World War II. While tyranny threatened the globe, Franklin Roosevelt oversaw the construction of the Jefferson Memorial. Even as war raged, he engraved “all men are created equal” into the heart of our capital—a reminder that America was not just fighting a war, it was defending a promise.

And in 1986, after the upheavals of Vietnam, Watergate, and inflation, Ronald Reagan led the restoration of the Statue of Liberty. He did not merely preserve a monument, he rekindled it—ensuring Lady Liberty’s flame would still shine for the enduring dream of America.

Each of these moments shared a conviction that monuments matter: that when we forget who we are, we must build something that reminds us of our spirit.

At this moment in our national story, we are again in need of such a reminder.

I have seen what happens when people forget what they are capable of. I have seen what happens when people tear down history. Tearing down history not only destroys the moral fabric of society, it creates a vacuum that is then filled with a false identity.

In 1982, I was nineteen years old, a woodworker in South Philadelphia. My life was built on repetition—honest labor, yes, but I felt trapped. I was going nowhere, fast.

Then, at 4:00 p.m. on October 21st, I stopped. And at 4:01, I stepped off that path. I quit my job, walked to a payphone, called the Philadelphia School of Art. No portfolio, no training, no certainty, just a pull—a hunger—to create something that revealed the human spirit.

That moment set the course of my life.

My nineteen-year-old self could not articulate it then, but I wanted to sculpt form and meaning back together, to restore what had been severed, to bring back a language embodied in that art—a language of resilience, order, beauty, and soul.

So I went back to the greats: Michaelangelo, DaVinci, Raphael. And that lost language was restored in the World War I Memorial.

It took nine years from beginning to end, and it was inaugurated on November 2024 at 7:19 pm, at sunset. There is nothing like it in the U.S.

→ Read the entire article on the Modern Age website here:

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.