Who Was the Most Decorated U.S. Serviceman of WWI?

Published: 1 September 2022

Most_Decorated

If someone were to ask “Who earned the most prestigious U.S. medals in WWI?” the answer most people might give is Sgt. Alvin York. The exploit that earned him the Medal of Honor (MOH) is legendary, and his name became synonymous with WWI. Having Gary

Cooper play his life on the silver screen in the 1941 flick Sergeant York helped a little, too.

Still, was he the one? There were 124 MOHs awarded for WWI, and a number of other candidates seem more likely. VFW magazine set out to answer this question. What we found might surprise you and at the same time lay to rest a few myths.

Criteria: The Medals

Our determination for the most decorated serviceman is based on the highest number of prestigious medals awarded, rather than sheer total numbers. For a fair assessment, only U.S. medals are counted. Many vets received foreign awards, but because

these were acts of valor by Americans, only U.S. awards will be considered here. It’s worthy to note that one of the candidates, Pfc. Charles D. Barger, received as many as 18 foreign medals.

To begin, one must first understand the hierarchy of the awards.

the medal and the quantity each man received. The Medal of Honor naturally heads the list as the U.S. military’s highest award. Its origins trace back to the Civil War. On Feb. 17, 1862, Congress authorized the president to present the Army’s

version.

The Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) falls next in line and was created by Congress on July 9. 1918. Then, for WWI only, comes from the Navy Cross. It was created on Feb 4, 1919, and was originally the third highest Navy decoration. An act of

Congress on Aug. 7. 1942, made it a combat award only. Today, it is the Navy’s second highest award.

The next award is the Silver Star, though it did not come about until Aug. 8, 1932. Its predecessor was the “citation star,” which was created by Congress on July 9, 1918. It was a small emblem warn on a campaign medal and awarded for “gallantry in

action,” a phrase open to broad interpretation.

After the Silver Star medal was created, with more stringent requirements, actions for citation stars were reviewed. Some were upgraded to the new Silver Star.

In all, the creation of these new medals allowed servicemen to be recognized more than once. The Medal of Honor is limited to just one award per wartime period by a service.

The additional medals also addressed the notion among WWI fighting men that the MOH had diminished in importance due to its over-distribution prior to WWI, particularly during the Civil War and the Indian Campaigns.

According to Warren Hastings Miller in his book, The Boys of 1917, MOHs awarded “during the war between the states were often for ‘valor in action,’ or taking a flag from the enemy.”

Miller goes on to say that servicemen felt a more characteristic award should be given that would be “in a class by itself,” hence the DSC. He also said that after the DSC’s creation, many preferred to receive it rather than the MOH.

Aside from these valor medals, one has to take into account the Purple Heart. For those who put themselves in the line of fire and were wounded, the medal should carry considerable weight. Barger, who served as a machine gunner and stretcher bearer,

heads that list with a phenomenal 10 “Hearts.”

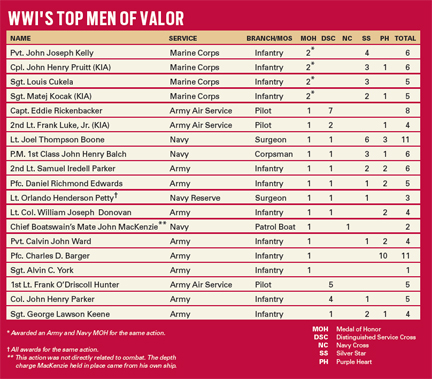

Top Men of Valor

Four Marines have the unusual distinction of being awarded both an Army and Navy MOH. However, the medals were presented for performing the same action. Marine units served under the Army’s 2nd Infantry Division. In a similar fashion, Navy personnel

during WWI received Silver Stars, then an Army award. One of these MOH recipients, Marine Pvt. John Joseph Kelly, earned four Silver Stars, topping the entire list.

The next eight recipients received both the MOH and DSC. One soldier, Pfc. Daniel R. Edwards, was nominated twice for the MOH. But as stated earlier, only one MOH could be awarded, so he received a DSC for one of the acts.

Because the Distinguished Flying Cross was not created until July 2, 1926, the Army had only the DSC to award for bracery in the air. Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker of the 94th Aero Squadron dominates this category with seven DSCs. He actually received

eight, but one was later upgraded to an MOH.

Rickenbacker was a fearless aviator, sometimes taking to the air without orders, and engaging enemy planes whenever he could. His war record of 26 air victories stood untouched until WWII.

Another flier, Lt. Frank Luke Jr., of the 27th Aero Squadron, received the MOH and two DSCs. The 21-year-old Phoenix native became known as the “Arizona balloon buster.” Luke racked up 18 air victories in eight days of flying. He destroyed a total of

14 German observation balloons before being killed on Sept. 29, 1918.

Perhaps the most fascinating discoveries for the most decorated were the Navy’s Lt. Joel Thompson Boone and Pharmacist’s Mate 1st Class John Henry Balch.

Boone was a Navy surgeon with the Marines. During the attack at Soissons in northern France on July 19, 1918, the 28-year-old dashed onto the battlefield to administer aid to wounded Marines. Twice he returned to the trenches for more dressings,

weaving through a fire-swept battlefield on a motorcycle.

Balch, attached to the 3rd Bn,. 6th Marines, also put himself in the line of fire when he created a forward dressing station on July 19, 1918, at Vierzy, France. He then repeated the act three months later on Oct. 5, 1918, at Somme Py, France. The

Edgerton, Kan., native administered aid for 16 hours straight at Vierzy.

Another relative unknown is 2nd Lt. Samuel Iredell Parker, of K Co., 28th Inf. Regt., 1st Div. over a period of two days, Parker led his platoon twice to plug a gap in Allied lines.

During the first day, his unit captured six machine guns and took 40 prisoners. On the second day, a German shell shot away the bottom part of his foot. He refused evacuation and continued to lead his platoon by crawling on his hands and knees.

Pfc. Daniel Edwards served with C Co., Machine Fun Bn, 1st Div. A man of brute strength at the age of 20, Edwards could carry a machine fun on his shoulders.

Edwards was recovering from wounds suffered at the Battle of Cantigny when he learned his unit was going back in battle. Without permission, he left the hospital, rejoined it in a trench at Soissons on July 18, 1918.

In the battle, a shell shattered his right arm and left him dangling from the trench wall. Hearing Germans approaching, he freed himself by severing his arm in order to fight them. He killed four of the enemy before the other four surrendered. On the

way back to his lines, a shell exploded nearby, severely wounding one leg and killing one of his prisoners.

Lt. Orlando Henderson Petty was a Naval Reserve surgeon. He received the MOH, DSC and Silver Star all for the same action.

On June 11, 1918, Petty was tending to the wounded when he was knocked to the ground by an exploding gas shell that tore his mask. He discarded his mask and continued treated the wounded. When the dressing stations was destroyed he helped a wounded

captain through the shellfire to safety.

Lt. Col. William Joseph Donovan, future “Father of American Intelligence,” served as commander of the 1st Bn., 165th Inf. Regt., 42nd Div. Known as “Wild Bill,” a moniker he earned as a football player at Columbia University, Donovan performed his

MOH act on Oct. 14-15, 1918, near Landres-et-St. George, France.

He led the battalion (originally designated as New York’s “Fighting 69th”) in the first wave of an assault against a well-organized enemy position. During the push, he gave his men constant encouragement, reorganized decimated platoons and

accompanied them in attacks. He was wounded in the leg and refused evacuation.

Setting the Record Straight

Not all MOH claims proved true. This was the unfortunate case for Sgt. George Lawson Keene. Highly recered after his death for receiving an MOH, research shows he is missing from the rolls.

Keene, a Crockett, Texas, native, graduated from high school at the age of 16 and planned to attend Texas A&M College, but entered the service instead. He was stationed overseas with K Co., 28th Inf. Regt., 1st Div., for 26 months, including

occupation duty. During the war, he suffered several wounds and was gassed.

On July 18-19, 1918, at Soissons, Keene rated a DSC when he led his troops in storming an enemy position, hurling grenades and capturing a German officer. That officer possessed maps showing the enemy’s positions. On the second day, Keene took over

command of the company when his captain was wounded and successfully led the attack.

But what about the MOH? The Baytown Sun (Texas) edition of July 19, 1981, claims Keene received one. Other prominent sources tout this claim, as well as a number of websites and blogs.

However, according to Laura Lowdy, archivist at the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, Keene never received the Medal of Honor.

“General Order No. 5, 1937, presented Keene with the DSC, not the MOH,” she said. “This is the same general order that is cited when people say he received the MOH.”

Sgt. Alvin York is another war hero whose fame was fanned by the pen of a reporter, namely George Pattullo of the Saturday Evening Post. York received an MOH, but no other awards, more was he wounded.

According to Dr. Michael Birdwell, archivist of York’s papers, and associate professor of history at Tennessee Technological University, Pattullo “focused on the religio-partriotic nature of York’s feat.” His portrayal of a Tennessee backwoodsman

performing a single-handed feat on the front lines is Europe conjured up images of Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone in the public’s eye.

York served with G Co., 328th Inf. Regt., 82nd Div. On Oct. 18, 1918, near Chatel-Chehery, he and 16 men came under machine gun fire that killed nine of them. York was ordered to silence the gun, so he put to use his hunter skills as a sharpshooter

and turkey hunter. At one point, six Germans rushed York, but he took them all out. In the end, the Germans surrendered and York and eight other men who survived the attack marched 132 prisoners back to the lines.

Even today, some accounts are still blown out of proportion, stating as many as 35 machine guns were blazing that day. According to Birdwell, “York always said that one gun was captured.”

“York never claimed that he acted alone, nor was he proud of what he did,” Birdwell wrote. “Twenty-five Germans lay dead, and by his accounting, York was responsible for at least nine of the deaths.”

York was a humble man who never craved the limelight, but who was thrust into it by journalistic exaggeration.

A Final Determination

Now to answer the questions of who was the most decorated serviceman of WWI. Because the top four were awarded two MOHs each for a single action, it’s hard to give them double credit. As noted, Kelly deserved special attention for his four Silver

Stars, six awards in all.

Yet two vets on the list seem more likely candidates for that distinction – Rickenbacker and Boone. Rickenbacker holds eight top medals to Boone’s two. However, one must consider Boone’s six Silver Stars and three Purple Hearts, 11 awards in all.

Rickenbacker and no other awards and no Purple Hearts.

One question to ask, though, is if the Distinguished Flying Cross was available during WWI, would the number of DSCs awarded to Rickenbacker be less?

Also, if we were ranking by sheer numbers, there is Barger to consider. He was wounded 10 times, plus was awarded an MOH. But he had no DSC or Silver Star. Boone’s awards top Barger’s in that respect.

Still, it is hard to ignore the fact that only one man hold the MOH along with seven of the nation’s second highest medal. With all due respect to Boone, our determination is that Rickenbacker holds more prestigious medals. Therefore, he should be

known as the most decorated serviceman of WWI.

What do you think?

This article is featured in the April 2017 issue of VFW magazine and was written by Robert Widener, former art director for VFW magazine.