Wars, Sedition, and Defining a ‘Clear and Present Danger’

Published: 11 October 2025

By Dustin Bass

via the Epoch Times BRIGHT website

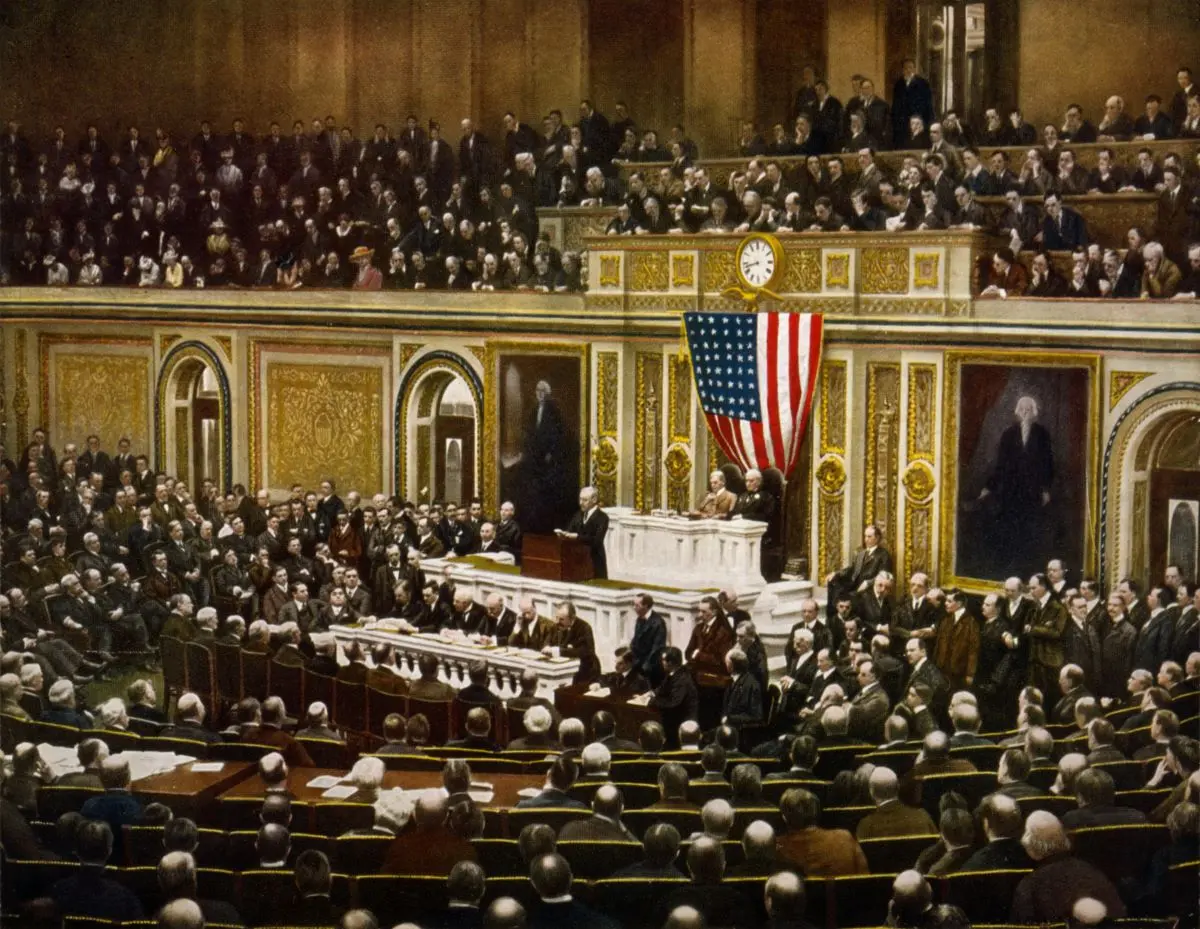

President_Woodrow_Wilson_asking_Congress_to_declare_war_on_Germany_2_April_1917

President Woodrow Wilson asking Congress to declare war on Germany on April 2, 1917. Library of Congress. (Public Domain)

In ‘This Week in History,’ subversives attempt to refute war legislation, forcing the U.S. court system to redefine the parameters of free speech.

On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson stood before a joint session of Congress requesting a declaration of war against Imperial Germany. Citing Germany returning to unrestricted submarine warfare and its attempt to ally Mexico against America, the president, who had recently won his second term on the campaign slogan “He Kept Us Out of War,” now found himself asking America to enter it.

“But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts—for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own Governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free.”

Two days later on April 4, the Senate passed its resolution to enter World War I by a vote of 82 to 6. In the early morning hours of April 6, the House of Representatives voted in favor of the resolution 373 to 50. War with Germany had begun.

Recruiting Soldiers

At the moment of declaration, the United States had a standing army just north of 125,000. The numbers paled in comparison to the major European powers involved in the war. The United States needed more soldiers.

Violators faced a fine of “not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both.”

‘A Clear and Present Danger’

Two months later, on Aug. 13, the Executive Committee of the Socialist Party in Philadelphia authorized the printing of 15,000 leaflets arguing that the Selective Service Act was an infringement on the 13th Amendment, which prohibited involuntary servitude. The leaflets were received and delivered a week later to men who had recently been drafted.

Charles Schenck, the general secretary of the Socialist Party, and Elizabeth Baer, who had taken the minutes for the party’s Aug. 13 leaflet resolution, were arrested. The two claimed their First Amendment rights had been breached, but the courts found them guilty of conspiracy to violate the Espionage Act, conspiracy to commit an offence against the United States, and unlawful use of the mail system.

→ Read the entire article on the Epoch Times BRIGHT website here:

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.