Lord of the Rings and World War I

Published: 1 September 2022

LRYPREScombine_images

Left, shot from the film, The Lord of the Rings. Right, photo taken at the Battle of Passchendaele, 1917.

By Rachel Kambury

The Lord of the Rings is a war story.

It borrows heavily from that grandest of traditions set forth by works like Beowulf and The Wanderer—Old English warrior poetry, by turns heartbreaking and bloody, meant to be spoken—and its author was steeped in the same fetid

waters that brewed the most famous novels to come out of the Great War in which he fought: All Quiet on the Western Front, Parade’s End, A Farewell to Arms…

Looking past the Elves, Dwarves, Hobbits, kings, and Istari, past the natural and unnatural magic, past the One Ring and its maker, war rests firmly at the heart of The Lord of the Rings.

So why, in all the years since its publication, has J.R.R. Tolkien’s epic never found its way onto any “Best-Of” lists of war literature? Why, in spite of the overwhelming number of parallels, has it never been counted among the greatest novels to

emerge from the events of World War I?

How could it not?

The roots of The Lord of the Rings broke ground during the war: there was 2nd Lt. John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, Battalion Signaling Officer to the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers, seeking relief—however temporary—from boredom, chaos, and

brutality with pen strokes and scraps of paper, writing “in grimy canteens, at lectures in cold fogs, in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candle light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire.”

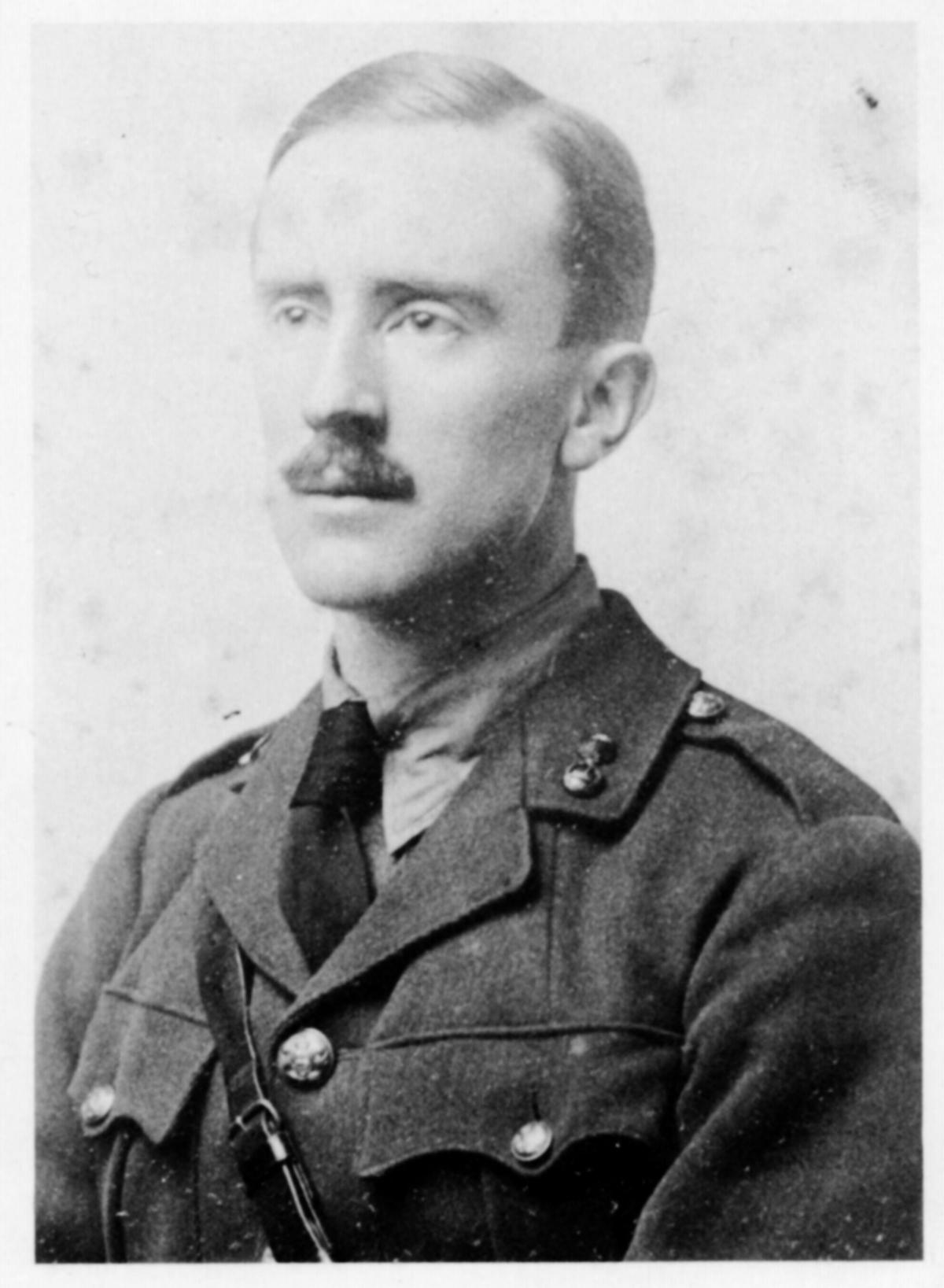

J.R.R. Tolkien in WWI Uniform. Image source: The Tolkien Trust

It was in between his duties as officer that Tolkien began to lay the narrative foundations of what would become Middle-earth. They were “fairy-stories,” so-called: little vignettes, concerning gnomes and sprites and elf-like creatures, the kinds of

stories with which Tolkien had been loosely enamored “since I learned to read.” It wasn’t until he was invalided back to England with trench fever during the Battle of the Somme—where two of Tolkien’s closest friends were killed—that “Tolkien wrote

out…the haunting epic of Gondolin, a city of high culture which is destroyed in a hammerblow by a nightmarish army.”

More stories followed shortly after, snippets of a larger world beyond the scope of any fairy-story Tolkien would have encountered in his childhood, but which would eventually become the grand mythos of Middle-earth, itself. That mythos would not be

called the The Silmarillion until the book’s publication in 1977, four years after Tolkien’s death, but its disparate pieces were brought to life both in the midst and in the aftermath of the Great War: Morgoth and the fall of Gondolin; Eä

and the Undying Lands; Ainulindalë and the War of Wrath.

There is a distinct causality between Tolkien’s experiences in combat and the literature he would write (and re-write, and revise, and re-write again) over the fifty-seven years that ensued. War was a catalyst for Tolkien: it was an unprecedented

experience that galvanized him to write stories unlike anything the world had ever seen before. “A real taste for fairy-stories,” Tolkien once explained, “was wakened by philology on the threshold of manhood, and quickened to full life by war.”

“This business,” he wrote in another letter, “began so far back that it might be said to have begun at birth…But the mythology (and associated languages) first began to take shape during the 1914-18 war…The kernel of the mythology, the matter

of Lúthien Tinúviel and Beren, arose from a small woodland glade filled with ‘hemlocks’ (or other white umbellifers) near Roos on the Holderness peninsula—to which I occasionally went when free from regimental duties while in the

Humber Garrison in 1918.”

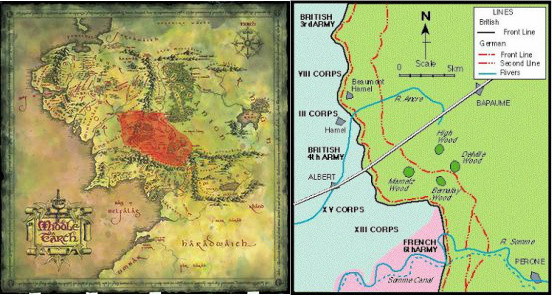

Left, map of Middle Earth from The Lord of the Rings film. Right, map of the Battle of the Somme.

I often think about places like the Somme, once a quagmire of a battlefield, and how it looks now—a liminal space between past and present where one can hear souls cry out if one listens hard enough; where the scars in the earth are as deep as they

were when they were first dug and blasted but are now covered over with grass; a place where, in a single day, more men died or were wounded than any other in the history of the British Army.

“On either side and in front wide fens and mires now lay, stretching away southward and eastward into the dim half-light. Mists curled and smoked from dark and noisome pools. The reek of them hung stifling in the still air.”

“[Sam] fell and came heavily on his hands, which sank deep into sticky ooze, so that his face was brought close to the surface of the dark mere. There was a faint hiss, and a noisome smell went up, the lights flickered and danced and swirled. For a

moment the water below him looked like some window, glazed with grimy glass, through which he was peering. Wrenching his hands out of the bog, he sprang back with a cry. ‘There are dead things, dead faces in the water,’ he said with horror. ‘Dead

faces!’”

Left, Dead Marshes. Source: Tolkien Gateway. Right, the author walking in the remnants of trenches at the Somme. Image courtesy of Rachel Kambury.

The Dead Marshes are impossible not to recognize by anyone at all familiar with trench warfare, at the Somme or elsewhere; pits and pools and the ghastly faces of the dead appearing from the mud, a site of horror barely concealed by the growth of

weeds and grasses over a long period of time…The Somme was Tolkien’s first experience of combat, the beginning of a years-long experience that would take the lives of almost all of his closest friends and return him—and many others of his

generation—to England forever changed.

But for all of the parallels between Tolkien’s lived experiences and the details in his works, he always maintained one thing: Middle-earth—its stories, its mythology, the journeys undertaken by its inhabitants—is not an allegory.

In a letter to his publisher written in the waning days of 1938, while Hitler in his seat of unimpeachable power stoked furor and the fires of future war, Tolkien wrote: “The darkness of the present days has had some effect on [The Hobbit].

Though it is not an ‘allegory.’”

Later, in 1944, a little more than a week before the Allied invasion of Normandy took place, he wrote: “’Romance’ has grown out of ‘allegory,’ and its wars are still derived from the ‘inner war’ of allegory in which good is on one side and various

modes of badness on the other. In real (exterior) life men are on both sides.”

And again, in a letter to one Mr. Straight in 1956, he pressed again the non-allegorical nature of his works: “I hope that you have enjoyed The Lord of the Rings? Enjoyed is the key-word. For it was written to amuse (in the

highest sense): to be readable. There is no ‘allegory’, moral, political, or contemporary in the work at all…I think that [the] fairy story has its own mode of reflecting ‘truth’, different from allegory, or (sustained) satire, or ‘realism’,

and in some ways more powerful. I did not foresee that before the tale was published we should enter a dark age in which the technique of torture and disruption of personality would rival that of Mordor and the Ring and present us with the practical

problem of honest men of good will broken down into apostates and traitors.”

Taking Tolkien’s adamant refusal of all things allegorical and The Lord of the Rings together pushes our understanding of the novel (and it is a single novel—don’t let the separate volumes fool you) into an interesting place—one that rejects

simplification and generalization in favor of something more dynamic. Tolkien wrote The Lord of the Rings for many reasons, chief among them to build a house for his created languages, and to provide Britain with a mythology beyond the

well-worn lore of King Arthur and his Knights. It was written with a mind toward realism—as real as Elves and Orcs and Nazgûl and Hobbits can be—and the sense that magic is less an external force that defies nature but is in fact of nature,

itself. Trees communicate through their roots; flowers bloom even in the most scorched earth; the sea consumes entire cities and creates new land; love is a powerful force as much as evil.

So if not an allegory for anything, what might we classify The Lord of the Rings as?

Why not a war story?

Tolkien as a young soldier. Image source: middleearthnews.com

I think of the Nazgûl as depicted in Peter Jackson’s films, mounted on Fell Beasts and scouring the Dead Marshes for the Ring: wheeling and arching over a wretched, pocked landscape, determined to seek out and destroy its intended target, unleashing

that unholy shriek which makes the blood run cold, and I wonder if Tolkien writing The Lord of the Rings had in mind the artillery shells that blasted those dank holes in the first place, at the Somme and elsewhere during the Great War. An

enemy that is heard before it is seen, that makes such an inhuman sound it immobilizes men, makes them panic and collapse in fear…how can it not be a war story?

I think of Frodo Baggins, returning home to a Shire he doesn’t recognize: a bucolic, green corner of the world rendered grey and flat and grim by industry and greed and hardship, and I wonder how does anyone not recognize a young man returning to his

home after a devastating world war, one that saw the almost immediate overthrow of agrarian life for industrialization and the loss of a generation? To say nothing of the feelings Frodo shares with Gandalf and Samwise at the end of his journey, which

are as blatant as anything expressed in a book that is explicitly about war and trauma:

“Alas! There are some wounds that cannot be wholly cured,” said Gandalf.

“I fear it may be so with mine,” said Frodo. “There is no real going back. Though I may come to the Shire, it will not seem the same; for I shall not be the same.”

“Where are you going, Master?” cried Sam, though at last he understood what was happening.

“To the Havens, Sam,” said Frodo.

“And I can’t come.”

“No, Sam. Not yet anyway, not further than the Havens…”

“But…I thought you were going to enjoy the Shire too, for years and years, after all you have done.”

“So I thought too, once. But I have been too deeply hurt, Sam. I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: some one has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep

them.”

The Lord of the Rings is not an allegory for World War I. But it doesn’t have to be to be of that war—born from it and in spite of it. And one needn’t strip away the fantasy elements to make it a war novel. The presence of magic does not

diminish its right to sit on the shelf next to Remarque and Ford and Hemingway. The Lord of the Rings is a complex investigation of war and trauma, nature and industrialization, comradeship and loss. Poplar or willow, Nazgûl or artillery

shell, marsh or trench, The Lord of the Rings occupies a unique place in literature, a cross-roads where Tolkien’s war and Middle-earth meet.

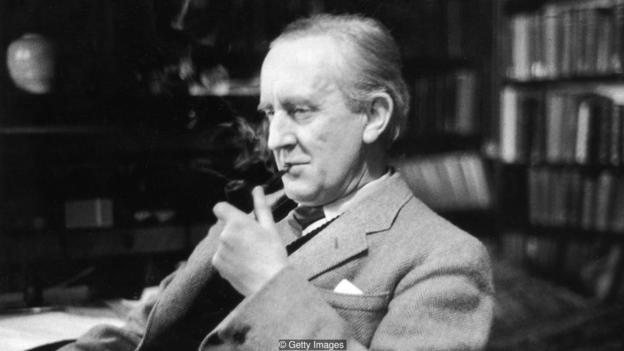

Tolkien many years after the war in 1955. Image source: Getty images

For more on Tolkien and the influence of WWI, see the BBC series, “How Was The Lord of the Rings Influenced by World War One?”

Author’s bio

literature and history. Rachel self-published her first work of WWII historical fiction, GRAVEL, in 2009, two months before she graduated high school.She

earned a BA in literature from Eugene Lang College in 2013 and studied war history at the American University of Paris. Her work has been published in The Wrath-Bearing Tree, Consequence Magazine, Quivering Pen, NYC Veterans Alliance, and Medium.com. She is editor for the online journal The

Wrath-Bearing Tree, an online journal established and maintained by combat veterans, The Wrath-Bearing Tree publishes essays, reviews, fiction, and poetry

on military, economic, and social violence written by those who have experienced military, economic, and/or social violence. She lives and works in New York City, where she is a volunteer at the NYC Veterans Alliance. To see more about her writing, see her website here and follow her on Twitter: @rkambury