The Road to America’s War in Europe

Published: 5 September 2022

HEADER_Cincinatti1910Shorpy_1000x500 (1)

The United States in the 19th Century

NOTE: The following summary focuses on context and background for World War I.

The United States began the 19th century as a new nation, little different from the original thirteen colonies along the east coast. Over the next hundred years, it vastly increased in size and population, and developed into the world’s largest agricultural and industrial economy. For most of this period, the U.S. focused on internal economic, political and social issues, but near the end of the century, it acquired overseas interests that involved it with international affairs.

In the first half of the century, the United States established itself as a viable nation and the dominant power in North America. The U.S. victory over the British in the War of 1812 firmly secured its independence. The Louisiana Purchase (1803) and victory in the Mexican American War (1846-48) expanded its territory across the continent. Protected by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, the U.S. avoided involvement in international politics. Through the Monroe Doctrine (1823), the U.S. claimed its status as the primary power in the Western Hemisphere while reaffirming its policy of remaining out of European affairs. During this period, the nation’s population grew rapidly, from 5 million in 1800 to 23 million by 1850.

The middle part of the century was dominated by debate and conflict over slavery, culminating in the American Civil War. The Union’s victory over the seceding states of the Confederacy ensured that the United States would continue as a single, unified nation. However, divisions and resentments between Northern and Southern states remained. Furthermore, although the Civil War ended slavery, black Americans were not integrated into American society, and were forced to embark on a struggle for equal rights and opportunities that continues to this day.

In the latter part of the century, the United States transformed from an inwardly-focused nation of small farmers and merchants to an industrial society with overseas interests.

Settlement and development of the West drove much of this economic growth. Military action and coercive treaties pushed American Indian tribes from their lands, opening up territory for settlement. Drawn by free land granted by the Homestead Acts, settlers cleared and cultivated millions of acres for farming. The discovery and development of oil fields and major metal deposits fueled industrial production. Innovations in manufacturing led factories to spring up in cities and towns across America. Railroads transported resources and goods throughout the country, and to coastal ports for overseas trade. The first modern corporations were formed from the consolidation of railroad, oil, and steel companies, and major banks arose to invest in the new industrial economy.

The U.S. population continued to grow, reaching over 90 million by 1910. This growth was fueled in part by a surge in immigration between 1880 and 1910. 17 million immigrants, attracted by the promise of free land and better wages, expanded the size of the American workforce while increasing the diversity of American society. At the same time, the expansion of industrial production and increased mechanization of farming led millions of Americans to move from the countryside into cities. In 1860 just one in five Americans lived in a city; by 1910, nearly half the population were city-dwellers.

Industrialization and urbanization came at a cost. Conditions in factories were dangerous and often unsanitary. The rapid, unplanned growth of cities resulted in unsafe and unhealthy living conditions in working class neighborhoods. Child labor was widespread. Immigrant laborers with limited English faced exploitation and discrimination. Political machines controlled cities through bribery and corruption. Unregulated corporations and banks created monopolies that controlled entire industries and were able to manipulate prices and wages.

The Progressive movement arose in response to these problems. Labor activists and unions fought for improved conditions, fairer wages, and shorter work weeks. Journalists exposed abuses and corruption by politicians and corporations. Legislatures passed laws restricting child labor and creating new schools and compulsory education. Other legislation regulated the activities of corporations and banks. The Women’s Suffrage movement gained new momentum thanks to a series of victories that gave women the vote in many western states. The era marked the beginning of broader government intervention on behalf of American citizens.

Near very end of the 19th century, the United States acquired significant overseas interests for the first time. Its victory over Spain in the Spanish-American War (1898) gave it control of nearby Cuba and Puerto Rico as well as the far-off Philippine Islands and Guam. These acquisitions spurred the U.S. to annex Hawaii, American Samoa, and other Pacific Islands in order to support its new possessions.

Thus, by 1914, the United States was the world’s leading agricultural producer and industrial power. Its population was larger than any European nation except Russia. Most Americans remained hesitant to become involved in international issues. However, the nation’s multicultural population, increased trade and financial ties with Europe, and new overseas territories made it more connected than ever before to global affairs.

The Debate over Intervention

When war broke out in Europe, the United States immediately declared its neutrality. President Woodrow Wilson stated that America must be “impartial in thought as well as in action.”

For a century, the U.S. had stayed out of European affairs. Most Americans preferred to continue this policy. The country was growing into its potential, and had emerged as the world’s largest agricultural and industrial producer. It was in the midst of a shift from a rural to an urban society, which created both opportunities and challenges. Americans were focused on issues at home, rather than conflicts overseas.

On the other hand, most Americans had European roots. The majority leaned toward the Allies, thanks to a shared language and heritage with Britain and ties with France going back to the American Revolution. At the same time, a large population of German-Americans sympathized with their mother country, and many Irish-Americans held strong anti-British feelings.

Germany’s violation of Belgium’s neutrality further tilted U.S. public opinion toward the Allies. Allied propaganda exaggerated German brutality, but there was truth behind the claims — German troops had burned down the medieval library at Louvain and had shot Belgian civilians and Allied sympathizers, including the British nurse Edith Cavell.

The war at sea also shaped U.S. opinion. Britain’s naval blockade was unpopular, as it prevented neutral nations from trading freely with both sides. At the same time, because of the blockade, the Allies were able to purchase far more U.S. goods and supplies than the Central Powers, often with loans from American financial institutions. This imbalance gave American businesses a vested interest in an Allied victory.

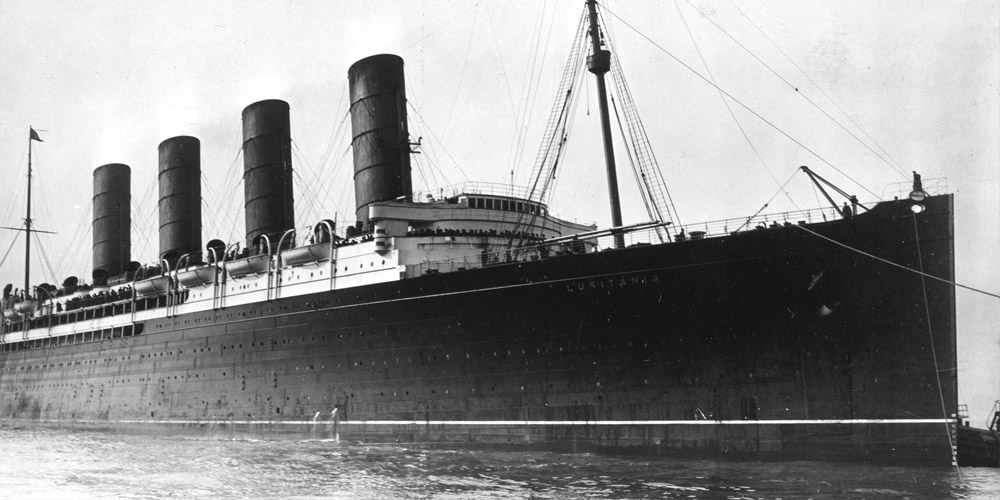

Also, although the British blockade was controversial, it was far less damaging than Germany’s policy of unrestricted submarine warfare. In early 1915, German U-boats began sinking all merchant ships going to or from Great Britain without warning. U.S. protests escalated until a German submarine sank the passenger liner Lusitania on May 7, killing 1,198 people, including 128 Americans. U.S. outrage exploded, and Germany halted unrestricted sinkings.

By this point, U.S. public opinion was firmly against Germany. A “preparedness” movement arose that argued the U.S. needed to build up its military in case it was pulled into the war. Preparedness was backed by many prominent Americans, including former president Theodore Roosevelt. It also gave rise to the Plattsburg Movement, a series of summer camps that taught attendees basic military skills.

However, there was still no widespread support for the war. In the end, preparedness advocates were able to achieve only a small increase in the U.S. Army and Navy. In November 1916, President Wilson’s peace position was validated as he won re-election with the slogan “He kept us out of war.” Yet less than four months later, he would ask the U.S. Congress for a declaration of war.

Relief Efforts and Volunteers

Although the United States was officially neutral, American organizations and individuals found ways to get involved in the war, through fundraising, aid efforts and volunteerism behind the lines and in combat.

Feeding a nation

Immediately after the war began, Belgium faced a food crisis. The country imported most of its food, but it was now isolated by the German occupation and the British blockade.

An American-led group founded the Commission for the Relief of Belgium (CRB). Headed by future U.S. president Herbert Hoover, the all-volunteer effort raised funds, collected food supplies, chartered cargo ships, and organized distribution efforts. All the while, it navigated its way through a complex web of diplomatic and military considerations in order to ensure that food reached Belgian civilians.

The CRB fed 7.3 million Belgian and 2 million French civilians between 1914 and 1919. It demonstrated that humanitarian relief could be successfully delivered into an active war zone, and set a standard followed by aid organizations to this day.

Saving lives

When war broke out, Americans living in Paris organized a field hospital and ambulances to help the French Army. This effort evolved into the American Ambulance Field Service (later the American Field Service, or AFS) through which volunteer drivers helped save the lives of thousands of wounded French soldiers. Other organizations raised ambulance units in France and on other fronts. Ernest Hemingway famously drove for the Red Cross in Italy. Most volunteers paid their own way to Europe, and covered their own expenses.

American women played a large role in providing medical support to Allies. A number drove ambulances, many more were nurses, and some wealthy women funded and ran hospitals. One newlywed bride and her husband even spent their honeymoon volunteering in France in 1915.

Joining the fight

Despite U.S. neutrality, many young American men were eager to join the action, especially on the Allied side. Thousands crossed into Canada to join the British war effort. Others, including the poet Alan Seeger, served with the French Foreign Legion.

Some American volunteers flew with the Lafayette Flying Corps or the Lafayette Escadrille, attached to the French Air Force. Many of these orig- inally volunteered with the American Field Service. Others came from the Foreign Legion, including Eugene Bullard, the first black fighter pilot.

When America entered the war, most of these volunteers were transferred to U.S. command. Bullard was denied a position in the U.S. Army Air Service, due to his race. Yet he, like many other American volunteers, received numerous honors and decorations from the French government.