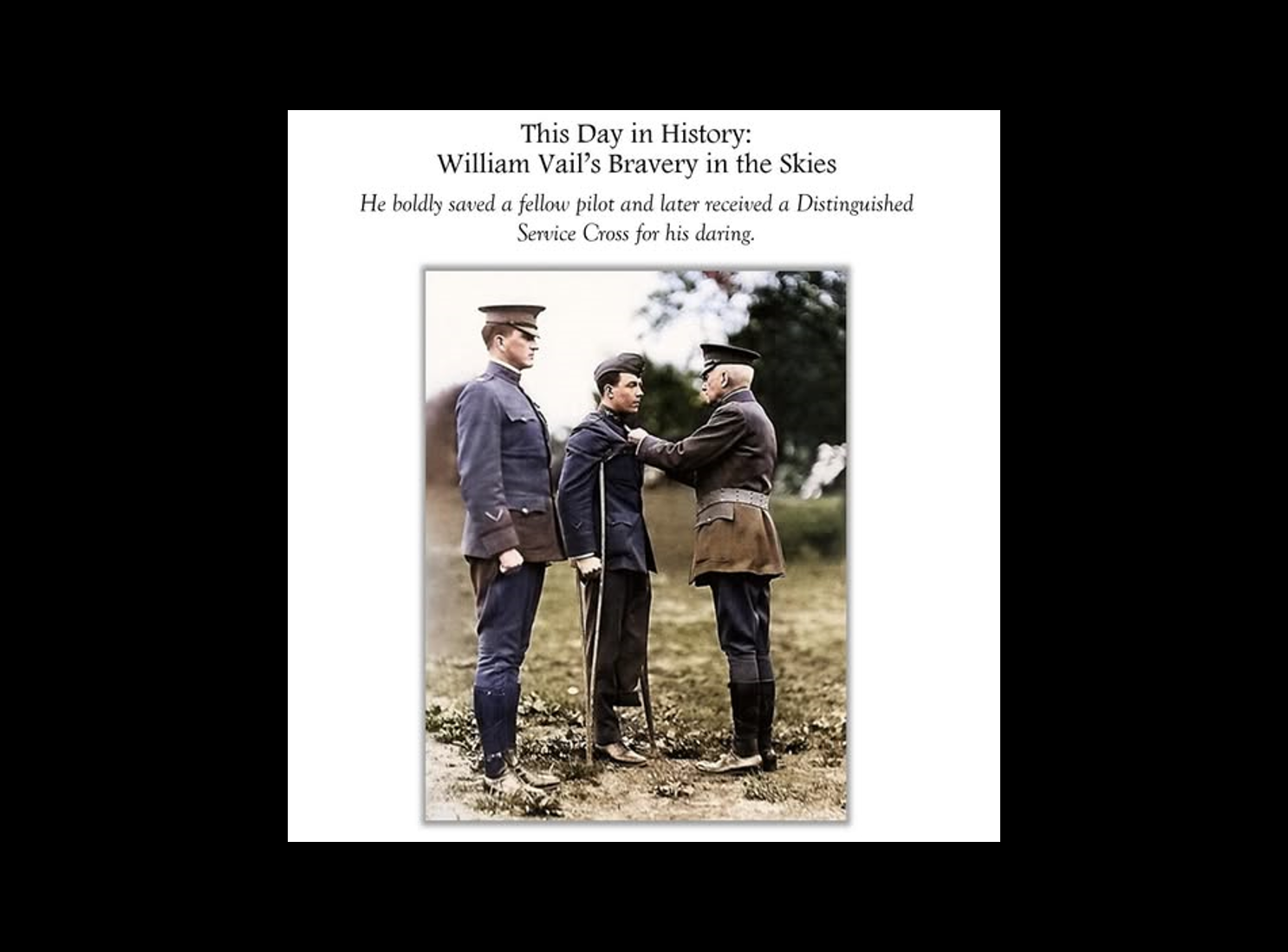

This Day in History: World War I Hero Lt Vail’s Courageous Actions

Published: 6 November 2025

By Tara Ross

via the This Day in History Facebook page

William Vail award framed

His action was one of the final aerial battles of World War I.

What must it have been like for those early pilots, flying in open-air biplanes, even as they fought off German fighters?

First Lt. Vail was on patrol with another pilot that day. He and Lt. Josiah Pegues were flying near the Argonne Forest, with Pegues in the lead.

Suddenly, the two pilots spotted a German observation plane. Pegues dove toward it, since he was in the lead. Neither pilot at first saw that more enemy were directly overhead. Now those enemy had set their sights on Pegues as he rushed forward.

Vail was the first to recognize what was happening.

“I then had three options,” he later wrote author Charles Woolley, who was writing a book about World War I fighter pilots, “to go with Pegues and let the outnumbering enemy strike at us from above; to put my nose down and retreat with every ounce of speed in my Spad . . . or to pull up the nose of my Spad and meet the nine [four first sighted, then five more appeared] down-diving enemy planes head on.”

Pegues had not yet seen the danger, so Vail chose the latter option: He would engage the enemy planes currently pursuing Pegues.

“Odds of nine to one were not odds,” Woolley concludes in Echoes of Eagles. “It was a death sentence.”

Nevertheless, the battle between the single American pilot and nine German Fokkers was joined.

Nevertheless, the battle between the single American pilot and nine German Fokkers was joined.

“Bill shot at anything that passed in front of his machine gun ring sight,” Vail’s son Gregory reports, citing his mother’s description. “One after another, the German aviators pulled alongside Bill as if his Spad were standing still. Bill could see his adversaries close up, their eyes blinking behind their goggles.”

One estimate has Vail being shot at 150 times.

“I seemed to have been surrounded by all of the enemy planes,” Vail later wrote his parents. “They were all shooting at me. Of course, I was shooting, too, but I knew I was greatly outnumbered.”

His plane was getting cut up by enemy fire, but two final hits did him in: First, his left leg took a hit. Then, his engine took a hit. He was going down, with the enemy firing at him the whole way.

“I went into the earth in practically a vertical dive,” he wrote Woolley. “Having no engine power and the soft mud of France there in the Argonne saved me from death.”

He was trapped in the plane, with his face pressing into the mud. He’d managed to turn his head just enough to breathe, yet he likely wouldn’t have survived but for a few Americans who witnessed the crash.

Together, those soldiers managed to get him out of the wreckage. Amazingly, they also managed to evacuate the (by now unconscious) Vail when the enemy began firing on rescue efforts. For about 90 minutes, they half carried, half dragged him to a first-aid station, “each step through the cratered, muddy field suctioning their boots into the muck,” Gregory writes, “bullets flying around them . . . .”

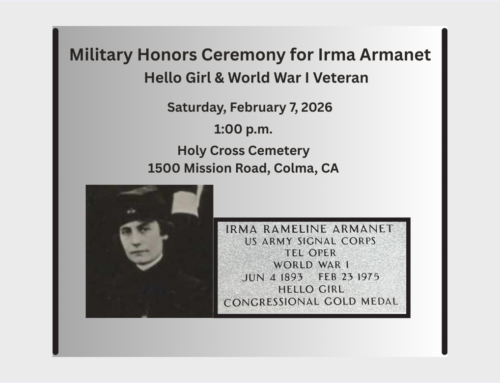

Vail would survive, although he lost his left leg. He was recommended for a Medal of Honor but received a Distinguished Service Cross instead.

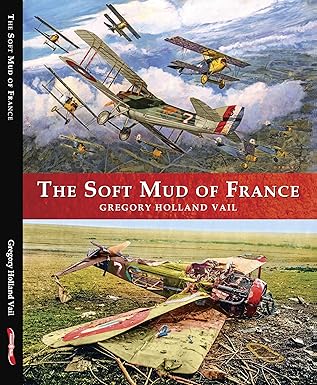

Much of his story might have been lost to history but for Gregory’s work in finding and preserving his father’s letters and other battlefield accounts documenting the action. His book, The Soft Mud of France, was written to honor his father. But he also hopes to get his father’s Cross upgraded to a Medal of Honor.

He acknowledges the high standards for Medal recipients, concluding “Bill Vail met that standard without question.”

⇒ Read the entire article on the This Day in History Facebook page.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.