The “Maryland 400” in the Great War

Published: 13 December 2025

By Dianne Smith

Special to the Doughboy Foundation website

115th Infantry Regiment

Company H, 115th Infantry Regiment

Sometimes in wartime, new units are formed. For example, the US Army saw fit to post the four permanent African American regiments (9th, 10th, 24th and 25th) elsewhere, form two entirely new divisions (the 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions), and send them to Europe as part of the American Expeditionary Force. But in other cases, units with military heritages dating even before the Revolution, which had been reorganized as National Guard units, were sent overseas under Pershing. Such is the case of the 1st Maryland Regiment, the “Maryland 400,” which had transitioned and played a role in World War I. It is the seventh oldest regiment in the U.S. Army (predating the U.S. Army by seven-and-a-half-months), and it is one of only 30 units in the Army and Army National Guard today that can claim colonial-era lineage.

The origins of the unit lie in the Baltimore Independent Cadets, formed on 3 December 1774 and led by Captain Mordecai Gist. The Maryland Assembly sent its first regiment to the Continental Army on 1 January 1776. The unit began as “Smallwood’s Battalion, “authorized by Maryland on 14 January 1776. It comprised of three companies recruited from Baltimore and six from Annapolis under the command of Colonel William Smallwood, a veteran of the French and Indian War. Following the Declaration of Independence, the regiment was transferred to the Continental Army on 6 July and placed under Lord Sterling’s Brigade. The unit saw action in New York and New Jersey during 1776. In January 1777, the battalion was redesignated the 1st Maryland Regiment and subsequently engaged in all the major northern campaigns (Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth) although it wintered in Wilmington, Delaware, not Valley Forge. In April 1780, the regiment was transferred to Nathaniel Greene’s Southern Department where it fought at Camden, Cowpens, Guilford Court House – and Combahee Ferry, South Carolina, ten months after Yorktown. Eventually Smallwood’s unit grew into seven different Maryland regiments, known collectively as “The Maryland Line.”

The regiment earned the title “The Maryland 400” (or “Washington’s Immortals”) for its performance at the Battle of Long Island (Marylanders prefer to call it The Battle of Brooklyn), by single handedly holding off superior British and Hessian forces as the Continental Army retreated to save itself from destruction. Unlike other early units, the initial battalion was well trained, well equipped (including bayonets) and well led; that reputation for steady competence followed with its expansion. With Smallwood absent that day, Stirling was in command. When 2,000 British and Hessian forces under Cornwallis surprised and encircled the Americans, Stirling ordered all forces, other than the four companies of the 1st Maryland and a few Delawareans, to escape.

The Marylanders, who were outside the fortified position on Brooklyn Heights, engaged the British, who were massed around the “Old Stone House,” a thick-walled field stone and brick de facto fortification filled with British soldiers who had a cannon on the second floor. Lord Stirling and the “Maryland 400” did the unexpected. They charged towards the Old Stone House with their muskets and bayonets, where (according to a survivor), the British “infantry poured volleys of musket balls in almost solid sheets of lead” at the attackers. Six times the Marylanders charged in fierce fighting, twice actually managing to eject the British from the house. As British reinforcements poured in and American casualties mounted, the survivors were force to withdraw; regiment is a misnomer as few reached American forces. Two hundred fifty-six lay dead on the field and around 100, including Stirling, were captured. Many of those prisoners died in captivity in the prison hulks in New York harbor. Their sacrifice allowed the rest of Washington’s army to escape disaster, enabling the retreat from Brooklyn to Manhattan Island and ultimately into New Jersey, thus preserving the fledgling American Army. Not yet two months after the Declaration of Independence, the collapse and destruction of the Continental Army that day would assuredly have resulted in the collapse of further military operations and the very continuance of a fight for independence. Following a well-worn pattern, defeat would be followed by the brutal execution of Washington and the other “traitorous rebels.”

When the Maryland Militia was reorganized 11 years after the Revolution, several Baltimore volunteer militia companies – including many ex-members of the Maryland Line- established the 5th Regiment of Militia, which fought gallantly at the Battle of North Point in September 1814, but the unit broke up in 1861 when most members went south to fight for the Confederacy as the 1st Maryland, C.S.A. The 5th Regiment was reborn two years after the end of the Civil War, under the new Maryland flag which consolidated the Confederate flag with the traditional orange/black flag flown by Union Maryland units. That unit served in the Maryland National Guard.

The 5th Regiment was federalized in August 1917 and attached to the newly established 29th “Blue and Gray” Division, so named because it consolidated National Guard units from “northern (blue)” and “southern (grey)” states. The 5th Regiment was consolidated with the 1st and 4th Maryland to form the 115th Infantry. The new colors for the 115th included the Maryland state colors, the “Rally Round the Flag” motto, showing white for infantry, a clover (Spanish-American War service), and a cactus (1916 Mexican border duty), alongside the Maryland crest’s Cross Bottony (a cross with trefoil ends).

Maryland contributed the 115th Infantry Regiment (Company H shown above) and the 110th Artillery Regiment and Virginia contributed the 116th Infantry Regiment to constitute the 58th Infantry Brigade. New Jersey provided two infantry regiments that formed the 57th Infantry Brigade. Just under 6,900 Maryland national guardsmen mobilized to serve in the 29th Division and deployed to Camp McClellan, Alabama, for pre-deployment training. In November 1917, 1,000 draftees from Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, and the District of Columbia joined the division, while in January 1918, the 1st Delaware Infantry separated to form the separate 59th Pioneer Infantry Regiment. In May 1918, remaining vacancies were filled by 5,000 more draftees from New York, New England, and the Midwest.

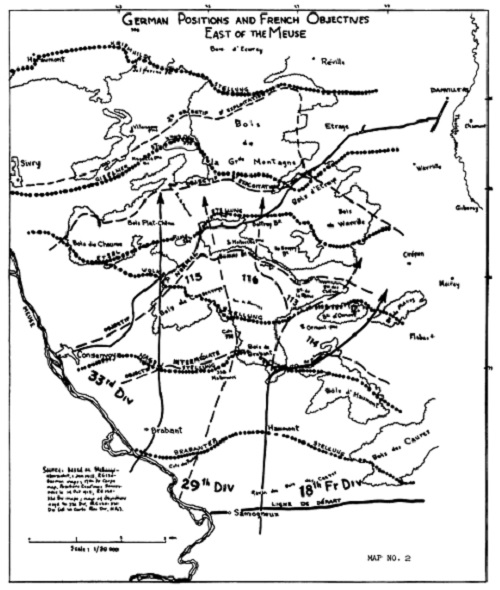

The division, led by Major General Charles G. Morton (right), departed for France in June 1918; its advance detachment reached Brest, France, on 8 June. When the rest of the division arrived later that month, they initially took up defensive positions in Haute, Alsace. In October 1918, the 29th Division engaged German forces in the great Meuse-Argonne offensive, the largest land battle in American history. When the broader Meuse-Argonne campaign began on 26 September 1918, the 29th Division was initially held in the Army reserve. On 8 October, the division launched its first major engagement. Alongside the 33rd Division, they were ordered to cross the Meuse River and clear the enemy from the heights east of the river to stop flanking fire that was stalling the general Allied advance and neutralize German artillery positions that were inflicting heavy casualties on Allied troops from these vantage points. The division advanced toward key areas, including Dead Man’s Hill (“Le Mort Homme” was a pair of small hills (Côte 295 and Côte 265) northwest of Verdun that became infamous during the 1916 battle due to the horrific, sustained combat and massive loss of life there). Two years later Maryland’s 115th and Virginia’s 116th Regiments led key attacks uphill, successfully capturing enemy strongpoints.

The division faced constant gas and high-explosive fire from German artillery. Sergeant Clyde Anderson of the 324th Artillery Battalion argued that the fighting there was “the hardest place on the whole front” with the constant shelling:

“We went from the Forest of Mers to Verdun….We took up a position near Dead Man’s Hill and talk about artillery, both sides had enough there to blow up hell! Everything from a one pounder to a sixteen-inch-rifle. There was a battery of British on a railroad just back of our picket line. The German planes came over and located them and in about a half an hour they were just shooting the hell out of things. The shells which Fritz [Germans] shot at them when they struck in the soft ground they would make a hole large enough to put the hen house in and have it all below the level, and they also made noise enough to scare the devil.”

Progress was often measured in meters due to heavy enemy resistance and a persistent gas atmosphere maintained by German forces. [See U. S. Army Chemical Corps Historical Studies Gas Warfare in the World War The 29th Division in the Dies de Neuse in October 1918 for a detailed study. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA955198.pdf).

Despite thorough gas defense training, the division suffered almost three times as many gas casualties as all other battle casualties combined. Initially, the division was slow to recognize the cumulative effects of persistent gas as a major threat, being more familiar with sharp, high-casualty gas concentrations rather than prolonged, low-level exposure which proved highly effective at producing casualties over time.

Over 21 days of continuous combat, the division advanced seven kilometers into the Hindenburg Line, captured more than 2,148 prisoners, and destroyed over 250 enemy machine guns and artillery pieces. However, it was at the cost of 5,691 men killed or wounded, including 170 officers and 5,521 enlisted men – a casualty rate over 30 %. Three men were awarded the Medal of Honor: Private Henry Costin, Sergeant Earl Gregory, and 2nd Lt Patrick Regan.

After the war, the 5th Maryland was reorganized in Baltimore. Just prior to the 115th Regiment’s activation in February 1941, the War Department assigned it a new designation: the “175th Infantry,” the title it holds today. Its unit crest encircles the number 5 to honor its predecessor. That iteration of the Maryland 400 found ever greater glory on D-Day, landing with the first wave on Omaha Beach. But that’s another story…..

Supporters of the 1st Maryland have initiated a program to fund a unit tribute for the “Maryland 400” at the National Museum of the US Army in time for Memorial Day 2026. All contributions are tax deductible. For information or to donate (any amount is appreciated), scan this QR code:

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.