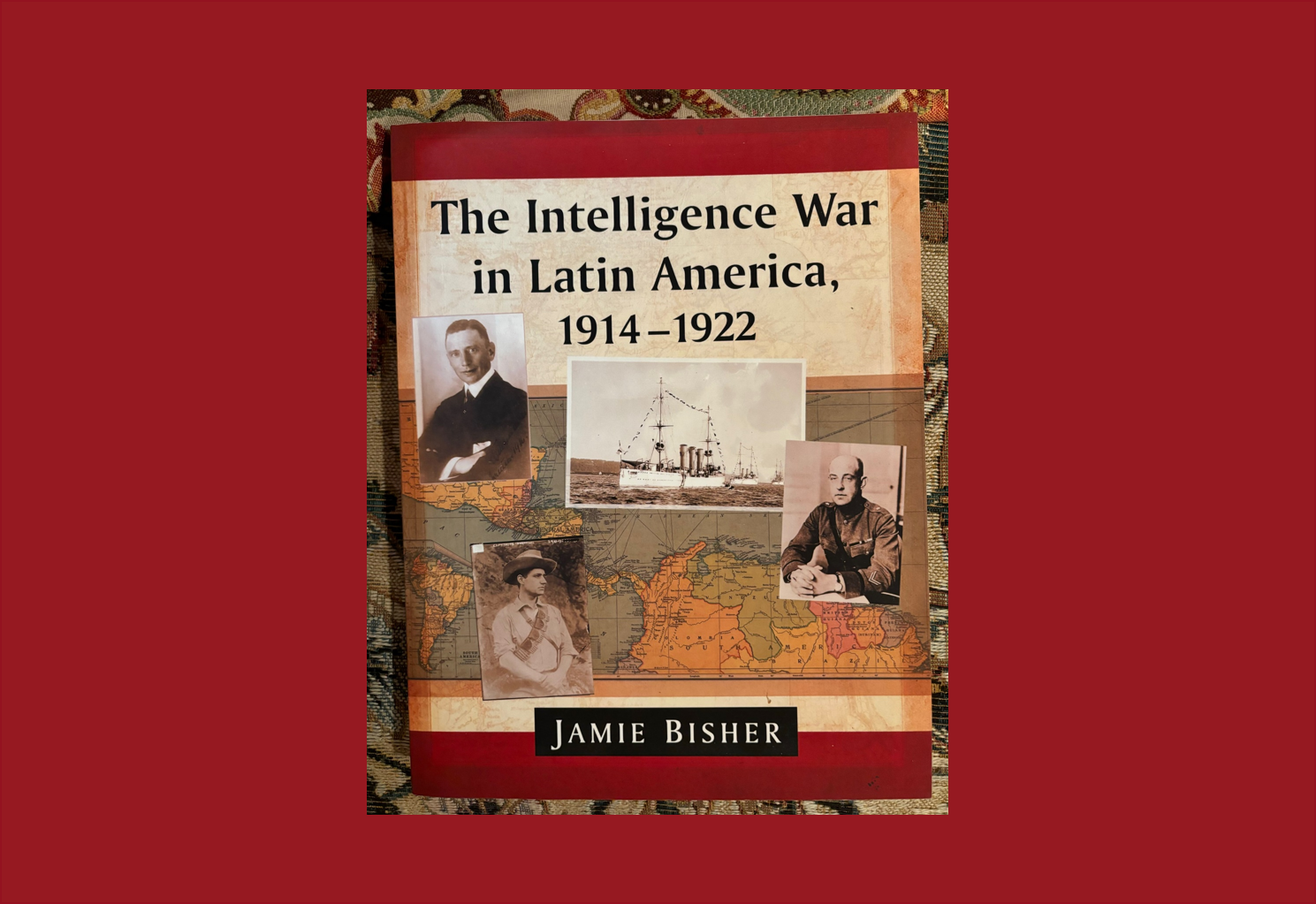

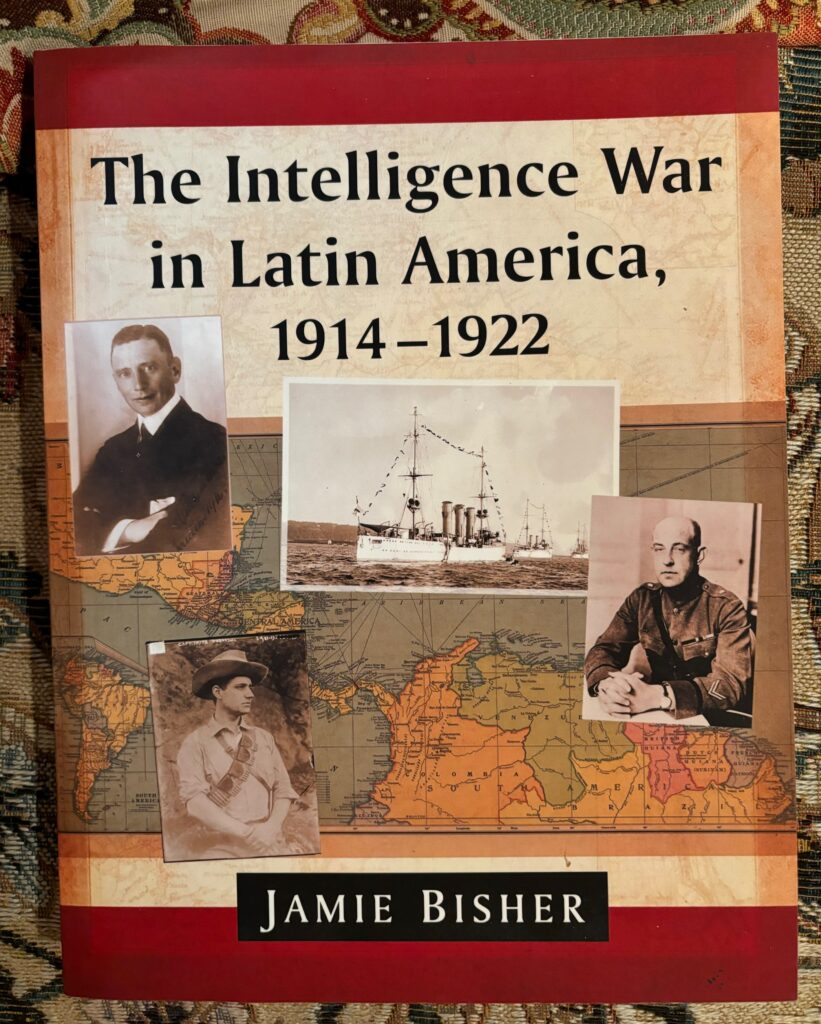

The Making of “The Intelligence War in Latin America 1914-1922”

Published: 24 July 2025

By Jamie Bisher

Special to the Doughboy Foundation website

Cover framed

How the Book and Website Came to Be

To a child, a dented French Adrian helmet, a crusty German pickelhaube, a deformed leather gas mask and a rusty bayonet were enchanting icons. They silently testified to Uncle Harvey’s culinary baptism as an Army cook in the American Expeditionary Force in France. The mementoes adorned the walls of his raucous restaurant on the outskirts of Atlanta, where Harvey Hester’s gastronomic mastery was embellished with his adventurous tales of the Western Front. We children of the late 1960s learned about the Great War from aging veterans like Uncle Harvey and through the chivalrous rivalry of Snoopy and The Red Baron in comic strips and spectacular TV specials. In the American memory, the First World War was largely confined to the mud and gore of trenches snaking through Belgium and France. In fifth grade, I was surprised when my history paper about the Versailles Treaty became controversial because I pondered if it had planted the seeds of the next world war. The offended teacher gave me a “C” on the paper, but I was intrigued that a 1919 treaty could arouse such emotions in 1967.

Movies of The Great War beyond the trenches fascinated me. “Lawrence of Arabia,” “The African Queen,” “Gallipoli” and “Doctor Zhivago” inspired me to read about campaigns in the Middle East, Africa and the Far East. When I began researching family history in the nearby National Archives, I was increasingly distracted by the diplomatic and intelligence reports of the World War from obscure corners of the globe. A folder of secret communications about Japanese intelligence officers meeting with their German opponents in Argentina and Peru in 1918 piqued my interest, and I was hooked. Why was our Japanese ally cavorting with the enemy? I soon realized that the Great War was much more complicated than the Snoopy versus Red Baron meme.

A box of US Army Signal Corps photos from an obscure 1918 campaign in the Far East inspired me to research and write “White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian.” My book recounted the amazing tale of the American Expeditionary Force-Siberia (AEFS) that had hunted rogue bands of escaped Austro-Hungarian POWs across the taiga in August 1918. The AEFS doughboys remained to secure the Trans-Siberian Railway for the repatriation of the Czechoslovak Legion, and found themselves in conflict with extremist Russian factions from both far left and far right. Our Japanese ally sided with the latter to contest the US presence in the Russian Far East and Manchuria—sometimes at gunpoint. This volatile chemistry between US and Japanese forces led me to the other side of the Pacific, where Washington and Tokyo vied to fill the vacuum left by the warring European powers in Latin America in 1914.

A box of US Army Signal Corps photos from an obscure 1918 campaign in the Far East inspired me to research and write “White Terror: Cossack Warlords of the Trans-Siberian.” My book recounted the amazing tale of the American Expeditionary Force-Siberia (AEFS) that had hunted rogue bands of escaped Austro-Hungarian POWs across the taiga in August 1918. The AEFS doughboys remained to secure the Trans-Siberian Railway for the repatriation of the Czechoslovak Legion, and found themselves in conflict with extremist Russian factions from both far left and far right. Our Japanese ally sided with the latter to contest the US presence in the Russian Far East and Manchuria—sometimes at gunpoint. This volatile chemistry between US and Japanese forces led me to the other side of the Pacific, where Washington and Tokyo vied to fill the vacuum left by the warring European powers in Latin America in 1914.

“The Intelligence War in Latin America 1914-1922,” published in 2016 by McFarland Books, was the result of my 25-year obsession to define the First World War south of our borders. Much history of The Great War had gone unwritten because many documents in the US National Archives remained classified until the 1980s. I felt compelled to reveal the wartime events that had remained in the shadows for three generations. Eventually, I created a website to make Latin America’s WWI history accessible to everyone.

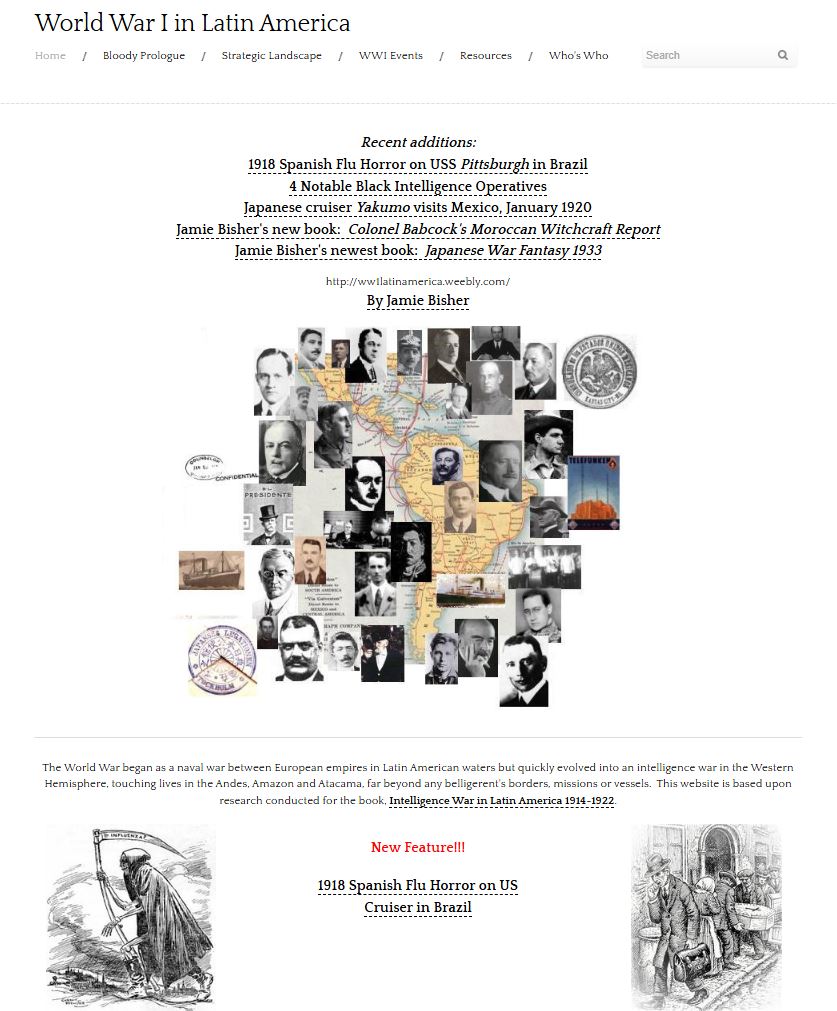

My website “World War I in Latin America” (https://ww1latinamerica.weebly.com) is a commercial-free, public website hosted on Weebly. The core of the website is the year-by-year chronology of intelligence-related events from 1914 into the mid-1920s, telling intriguing stories through dozens of photos, maps and documents. Supplementary webpages describe the background of spying and intelligence in Latin America, the strategic political landscape in 1914, and the reluctant metamorphosis of most nations from neutrality to polarized partisanship for either the Allies or the Central Powers. Special features examine topics like WWI in Belize, the Spanish Flu in Brazil, a who’s who of prominent figures, and a list of recommended books and websites.

My website “World War I in Latin America” (https://ww1latinamerica.weebly.com) is a commercial-free, public website hosted on Weebly. The core of the website is the year-by-year chronology of intelligence-related events from 1914 into the mid-1920s, telling intriguing stories through dozens of photos, maps and documents. Supplementary webpages describe the background of spying and intelligence in Latin America, the strategic political landscape in 1914, and the reluctant metamorphosis of most nations from neutrality to polarized partisanship for either the Allies or the Central Powers. Special features examine topics like WWI in Belize, the Spanish Flu in Brazil, a who’s who of prominent figures, and a list of recommended books and websites.

Why does the chronology extend beyond 1918? The war in the trenches may have ended with the Armistice, but the intelligence war did not. German consular bureaus in the Western Hemisphere did not even receive orders to burn sensitive documents until January 1919, and operations against pro-Allied governments and institutions continued for months. The eddies of intrigue would take years to subside.

What I Learned

As soon as I began poring through boxes at the National Archives, I was amazed at how deeply and quickly the First World War permeated the neutral Americas. Neutrality did not insulate any country from the affects of the global crisis.

The First World War was truly a global conflict. Off the West African coast, trans-Atlantic cables were hauled out of the sea and severed. German agents traversing the Gobi Desert were hunted down by mercenaries paid by the Chinese government. Japanese warships lay claim to Germany’s Samoan island possessions. Swedish saboteurs fighting for Finnish independence with secret German support planted anthrax at Russian Army outposts. Indian nationalists in California smuggled arms and propaganda on Mexican-flagged vessels through the Dutch East Indies. The European bloodbath had spawned a cascading series of uprisings, revolutions and political turbulence.

Even though the United States was neutral in the early years, the Americas—both North and South—had been entangled in the mess from the start in July 1914. Old country heritage, family ties, trade, finance, ideology, faith and loyalties of all shades tethered American communities to Europe and her colonial empires. Allied Canada, a staunch Commonwealth member, loomed above our northern border, British and French outposts dotted the Caribbean, while revolutionary Mexico and a number of Latin American governments cultivated diplomatic, military and commercial relations with London, Paris and Berlin. Every unfrozen continent except the Americas was dominated by colonial forces of the European empires, thus the fragile Latin American republics offered an open playing field, vulnerable to economic pressure and brute force, Uncle Sam’s pretentious Monroe Doctrine be damned. Latin America tantalized the belligerents with her natural resources, expatriate manpower, safe ports, and political and diplomatic support.

Cap Trafalgar (left) and HMS Carmania engaged in a furious shoot-out with artillery and machine guns on September 14, 1914. About 25 men were killed on both sides and dozens were wounded. (1923 painting by Charles Dixon, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich)

The war at sea had begun immediately in American waters in August 1914. German cruisers appeared and quickly vanished off California and the Mexican Pacific and in the Caribbean. A bloody artillery duel erupted in Brazilian waters between hastily converted luxury liners Carmania and Cap Trafalgar; the British suffered defeat at Coronel, Chile; the Germans endured defeat at the Falklands; and the Royal Navy’s frantic hunt for SMS Dresden involved Japanese and French warships on both sides of the Straits of Magellan before the smoldering maritime war devolved into blockades and forced boardings by Allied navies, and smuggling and sabotage by the Germans and their allies.

From April 1915 until the Armistice, the war in the Americas was a secret war. It was spearheaded by diplomats, intelligence officers and propagandists, avidly assisted by financiers, expatriate businessmen, mercenaries, stranded mariners, assorted revolutionaries and rebels, and a cornucopia of other colorful characters. Germany had anticipated a global conflict and began allocating resources to intelligence operations in the Americas many months before the declarations of war. Germany’s Etappendienst, an underground logistics and information-gathering organization, established outposts in every major port in the neutral Americas, from New York to Punta Arenas. The network surreptitiously arranged funds, fuel and supplies for German warships in American waters until their destruction in April 1915, then nimbly adapted to smuggling, sabotage, intelligence gathering, influence peddling and other dark arts. Allied intelligence frantically ramped up to contest the Germans, and many neutral nations exerted themselves to keep abreast of the combatants’ nefarious activities with their own secret police and budding intelligence agencies.

Lessons about WWI & Latin America

Modern warfare’s insatiable appetites and unexpected shocks can reverberate quickly around a planet interconnected by commerce, trade, finance and migration. Europe’s advanced war machines were sustained by vast amounts of money, material and men, drawn from every corner of the great empires and beyond.

Accordingly, expatriate communities throughout the neutral American republics were immediately mobilized in August 1914. Thousands of Austro-Hungarian, English, French and German military reservists and volunteers abruptly quit their jobs and boarded trans-Atlantic ships to report for duty. Mass departures in Lima, Buenos Aires and other Latin American cities rode swells of exuberant fanfare, with undulating flags, throbbing bands and frenzied mobs of expat patriots, all certain of exhilarating adventures, quick victories and joyful homecomings. International contracts were severed or cast in doubt, maritime insurance skyrocketed, economic sanctions strangled trade, global supply lines shuffled chaotically, and trans-oceanic cables were cut or rerouted. Every aspect of international business and finance was affected. I was astounded by the World War’s sudden and persistent impact upon neutral American republics. I was even more astounded by how history seemed to have forgotten the world war’s dark shadow over Latin America.

Pre-war planning and preparedness gave the Germans an early advantage the first nine months of the war. They also proved nimble at evading Allied sanctions and blockades, moving men, material, and money across the oceans—albeit with increasing effort and risk—until the Armistice. The physical damage caused by German sabotage, bombings and biological warfare was real but impossible to calculate. On the other hand, the public revelations about German outrages cast a villainous spotlight upon Germany, undermining overt support for Berlin.

USS Cyclops is last heard from before disappearing into the sea with 293 people. It remains the largest US Navy vessel to vanish without explanation, however, evidence suggests that German saboteurs may have been responsible.

The United States government was slow to react to the violent storm building around the hemisphere. In early 1917, naval intelligence suddenly had to determine if rumors of U-boats and secret German bases in Mexico were true. Military intelligence and the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation (BOI) awakened to facts and fears of German saboteurs and spies operating freely across borders north and south only after suspicious fires and explosions killed dozens of Americans, destroyed scores of industrial facilities and sank merchant ships. Geography—more than trust—compelled the Allies to rely on US intelligence to track and counter Germany’s extensive web of secret operators in Latin America.

The most amazing lesson that I learned was that the endgame of the intelligence war was open-ended. Soldiers from most armies gladly trudged home, demobilized and found peaceful pursuits soon after the eleventh month of 1918. Similarly, many intelligence services downsized drastically or shut down entirely. However, their operatives’ skills, networks and experience were in great demand in a chaotic world of redrawn borders, disputed territories, waxing and waning ideologies, and precious resources up for grabs. Intrigue, coups, revolutions and counter-revolutions flickered across Latin America throughout the interwar years, often aided and abetted by veterans of the secret war.

The chaos of the endgame makes it harder to analyze. As funds from Berlin dwindled, many German operatives found new employers with intelligence services of Mexico, Chile, Argentina and other secret non-state institutions skulking about the Latin American republics. Japan recruited both German and British intelligence veterans. At post-war international conferences in Paris and Washington, former Allies keenly spied on each other and tried to seduce Latin American delegations for nefarious purposes.

Why Should People Care

History that is neglected or flippantly discarded bears lessons that will have to be painfully relearned. The lessons’ cost in blood, sweat and tears is incalculable.

The First World War rattled the political landscape of Latin America. Competing cliques of pro-Allied and pro-German sympathizers polarized centers of power. At one end of the spectrum, Mexico, Venezuela and Chile opened their arms to the Germans; at the other end, Cuba, Panama and Brazil embraced US influence. Every other country felt the dizzying sway of elite factions wooed by one side or the other. Similar political and economic contests would repeat during WWII and the Cold War.

The First World War in Latin America forced changes that were both good and bad. Intelligence services were pushed to modernize and expand. Analysts in Washington and New York fine-tuned new methods of financial intelligence to track diplomatic payoffs, smuggling and contraband, sanctions evasion, blockade running, biological warfare alchemy and other nefarious activities. Propaganda and disinformation evolved into sophisticated endeavors. Eavesdropping and steaming open letters progressed to radio detection- codebreaking, signals intelligence and cryptanalysis. Biological warfare and poison gasses posed diabolical new threats. Governments realized that a capable intelligence agency could be an extra line of defense or a force multiplier.

The legacy of misinterpretations and distortions of history still haunt us today. Animosity between the US and Mexico traces its roots to the borderland troubles during and after the Great War, when German and Japanese operatives collaborated with Mexican intelligence against US targets. Indeed the rivalry between the US and Japan for influence in the Pacific revved up in Latin America from 1914 until 1941. As far-fetched as the Zimmermann Telegram sounds today, the idea of a German-Japanese-Mexican pact was not at all fantasy. US meddling in Central and South American politics intensified during the world war, driven by paranoia of German infiltration.

Most heroes—and villains—of the intelligence war in Latin America went largely unrecognized after the Armistice. Scores of men and women on all sides sacrificed their fortunes, careers, families and lives to serve distant homelands or vague ideologies. Likewise, many villains of the intelligence war escaped without consequences after destroying fortunes, careers, families and lives. Of course, one side’s hero may be an opposing side’s villain. My website “World War I in Latin America” aims to illuminate the deeds of both heroes and villains.

As a child in Atlanta, Jamie Bisher cultivated penpals in Russia and finagled visits to the Soviet Embassy in Washington. In his youth, he trekked through war-torn Central America after graduation from the Air Force Academy. He now works on international projects for an engineering firm in Maryland, but his passion is mining old intelligence files in the National Archives to grind out gritty, untold histories. His latest full-length book describes the spies, saboteurs, assassins and other intelligence operatives who brought World War I to the Americas. “The Intelligence War in Latin America, 1914-1922” has received positive reviews in the American Intelligence Journal, International Affairs (journal of Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs), CIA Studies in Intelligence, Latin American Politics and Society, First World War Studies and others. Bisher is the only feature writer to have ever published in both Soldier of Fortune and Cat Fancy. His features and articles have appeared in Air&Space, Atlanta History, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Belizean Studies (Belize), Bowie Blade, CEO, Class, Foreign Intelligence Literary Scene, HiTechNews Network (Russia), Honolulu Magazine, International Journal of Intelligence & Counterintelligence, Logistics Spectrum, Military History, Military History Online, Military Illustrated (UK), Naval History, Pets Today (Canada), Proceso (Mexico), Revolutionary Russia (UK), Sankei Shimbun (Japan), Submarine Review, The Intelligencer: The Journal of US Intelligence Studies and others.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.