The Legacy of WWI Photography: Influences on Modern War Journalism and Visual Storytelling

Published: 30 December 2025

By Shelby Lofgren

Special to the Doughboy Foundation website

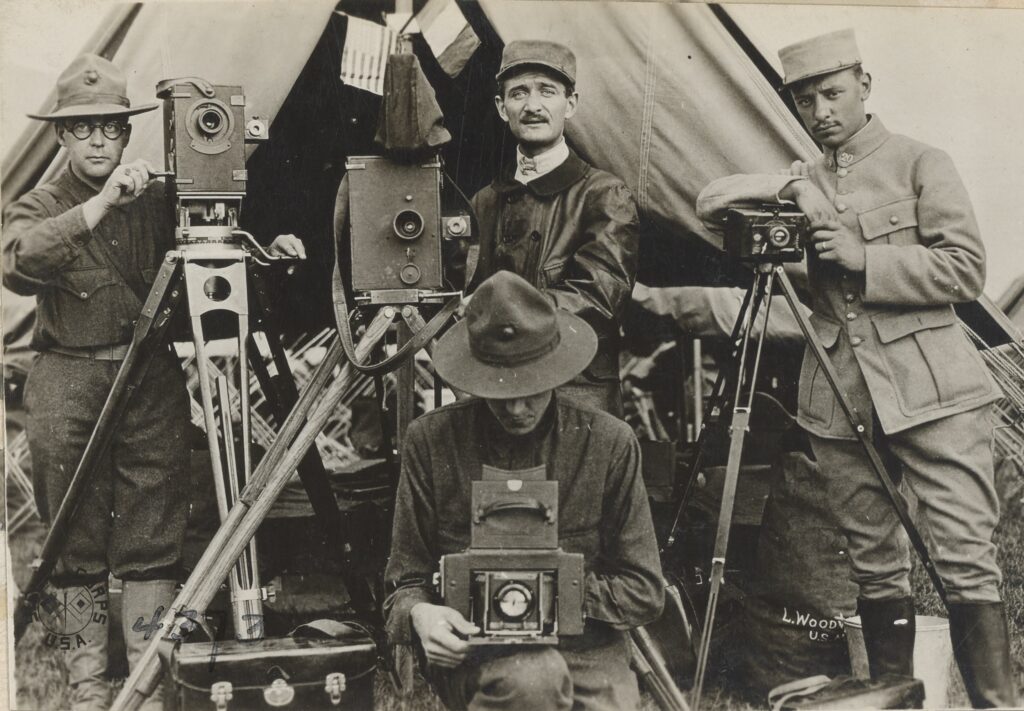

165-ww-103-00d-009-s

World War I U,.S. Army Signal Corps soldiers demonstrated various cameras used in training.

The advent of photography in warfare marked a pivotal moment in how the public perceived conflict. In 1914, cameras followed armies into mud, smoke, and broken towns, and the public saw war with new clarity. WWI photography turned distant fighting into shared sight, and it pushed readers to feel what reports could only describe. This shift changed how people judged sacrifice, strategy, and leadership, because an image could stay in the mind long after a headline faded.

The WWI Moment: When War Became Widely Seen

The Great War arrived during a media boom, with newspapers hungry for visuals and readers ready to believe what they could see. Photographs moved fast for the era, and they spread through prints, postcards, and public displays. In turn, images helped set the emotional tone of coverage, from pride and resolve to grief and disbelief.

Just as important, the camera changed who counted as a witness. Some images came from trained professionals, yet many came from soldiers with access that outsiders could not match. Also, families at home learned to read the war by faces, uniforms, and landscapes of damage. As a result, the camera became part of the war’s memory system, not just a tool for record keeping.

Why These Images Outlast the Headlines

Many WWI images began as proof, proof of victories, losses, and conditions at the front. Yet over time, they gained new roles as artifacts that carried personal and cultural meaning. Then, archives, museums, and family collections turned photographs into long-term references for teaching, mourning, and public commemoration. This is how images became more than historical records in the history of the world’s oldest photographs. Even today, we can see why WWI photographs still matter as objects of memory, craft, and interpretation. Next, this broader value helps explain why viewers return to the same frames across decades, searching for details that earlier audiences missed. Also, the act of revisiting can change meaning, because later viewers bring new knowledge, new ethics, and new questions.

That influence shows up in modern visual storytelling. Photo essays, documentary projects, and curated timelines often echo WWI methods, such as sequencing images to build a narrative and pairing pictures with precise captions. As a result, the Great War’s archive functions as a toolkit for how we make public memory through images.

Cameras, Film, and the Front Line

The technological limitations of early cameras greatly influenced what could be captured during wartime. Early twentieth-century camera design demanded planning. Film sensitivity was limited, lenses had constraints, and long exposures could blur motion. So photographers often captured what stood still, such as trenches, artillery positions, ruined streets, and posed groups. Over time, these limits shaped the look of war for generations, because the archive favored certain moments over others.

Access shaped content as much as technology did. The front line was dangerous, and movement was restricted, so photographers worked where they were allowed to stand. Also, many images came from staging areas, hospitals, rail lines, and camps, where the story of war was still real, yet easier to frame. In turn, modern conflict coverage still reflects this rule: what the camera can reach becomes what the audience thinks the war is.

Propaganda and Official Narratives

Governments quickly learned to manage images as carefully as words. Military authorities set rules on what could be photographed, what could be published, and what had to stay hidden. However, control rarely looked the same everywhere, and it changed over time, as morale, politics, and public pressure shifted.

Official releases often favored themes that supported the home front. Photographs could highlight discipline, camaraderie, and clean order, even when conditions were extremely harsh for soldiers. Also, images could be cropped, captioned, or paired with text that guided interpretation. WWI photography, therefore, offers an early lesson in media literacy: the frame is a choice, and the caption is powerful.

Alongside the official stream, private photos created a parallel archive. Soldiers photographed friends, camp routines, and moments of rest that official outlets ignored. Then, decades later, these personal collections helped historians fill gaps left by censorship. As a result, the Great War shows how archives can correct public narratives, but only if they survive and become accessible.

Visual Grammar That WWI Popularized

Under pressure, WWI photographers developed a visual language with lasting impact. Wide shots showed scale, trenches stretching into haze, craters cutting through fields, towns reduced to stone. Then, these images taught audiences to read devastation as a sign of modern war’s reach.

Portraits created another grammar. A face could carry fatigue, fear, pride, and loss, all in one frame. Also, group photos marked bonds, rank, and routine, and they helped families locate their loved ones inside the machinery of war. Meanwhile, images of gear, guns, masks, and vehicles gave the conflict a signature look, where humans often seemed small beside metal.

Quickly, the symbolism became essential. Mud became a shorthand for suffering, wire for danger, and ruins for rupture. So modern war photography often repeats these cues, even with new equipment and new publishing speeds, because the audience already knows how to decode them.

Modern War Journalism

Today’s conflict coverage moves faster, but the core problems remain. Verification matters, context matters, and access still shapes what gets shown. Then, social platforms add pressure, because images can spread before reporters confirm the place, time, and source.

Captions and metadata now carry more weight. A misleading label can turn a real image into false evidence, and that error can travel far. Also, editors face tougher choices about graphic content because audiences vary, and harm can be real. So many newsrooms rely on clear standards: explain what is known, avoid glamor, and center human dignity.

Embedded reporting brings familiar tradeoffs. It can offer proximity and detail, yet it can also limit perspective, since movement depends on military rules. WWI photography offers a steady reminder that proximity does not guarantee truth, and distance does not mean irrelevance, because both positions have blind spots.

WWI photography serves as a constant reminder that being close to a situation doesn’t always ensure accuracy. American and French Army photographers in World War I.

Readers and viewers carry responsibility too. Slow looking helps, because quick reactions often miss context, and they can reward outrage over accuracy. When audiences ask good questions, such as “Who made this image?” and “Why was it published now?”, visual storytelling becomes more truthful.

The Legacy, the Risk, and the Responsibility

The Great War taught the modern world to expect images alongside war reporting, and that expectation never left. Then, each new conflict renews the same tensions: access versus independence, impact versus harm, speed versus verification. WWI photography still matters because it shows how images can inform, persuade, mislead, and endure, all at once, and it pushes journalists and audiences to treat every frame as a claim that deserves context.

Shelby Lofgren is a content writer with a deep passion for people. She admires the art of “telling the story” and is dedicated to making a difference in people’s lives and approaches her work with fearless determination. She currently enjoys helping families relive their stories through her role at YesVideo, where her focus is on creating meaningful and engaging content.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.