The Assault on Free Speech in America

Published: 10 December 2025

By David Celley

via the dmcelleyauthor.com website

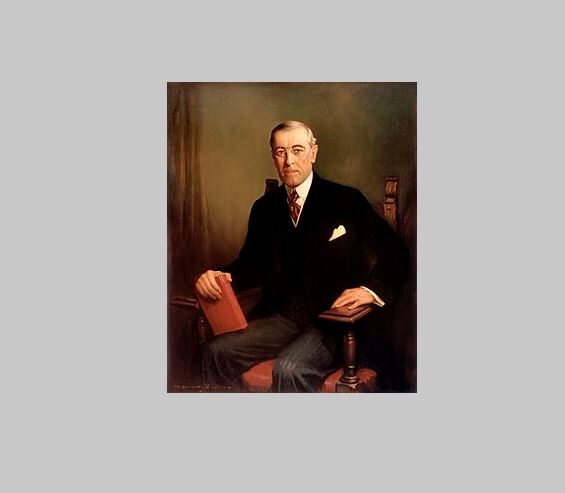

Woodrow_Wilson framed

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees all persons the right to free speech, among other things. At various times in our history this right has come under fire by actions taken by the government itself. One such time existed at a point in our history when you may not have expected it—the entry into World War I in 1917.

The United States Enters World War I: President Woodrow Wilson was elected to a second term in 1916 by campaigning to keep the U.S. out of the war in Europe. However, a few months after the election he received a message from the German government that announced Germany’s return to unrestricted submarine warfare. This was a dramatic turnaround for the policy that had been in place after the sinking of the RMS Lusitania by a German submarine in 1915 that killed over 1,000 including 128 Americans. Freedom of the seas was an important pillar of the U.S. economy, and the return to unrestricted submarine warfare pushed Wilson to ask Congress for War against Germany. War was declared on April 6, 1917, and a huge outcry in opposition to the war immediately arose. To stifle criticism of war Wilson pressed congress to pass the Espionage Act on June 15, 1917.

The Espionage Act and the Sedition Act Amendment: Under the new law the following became a crime: spreading information with the intent to “interfere with the operation or success of the armed forces of the United States or to promote its enemies’ success” and to make false reports or statements with the intent to “interfere with the operation or success of the military or naval forces of the United States or to promote the success of its enemies when the United States is at war, to cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, refusal of duty, in the military or naval forces of the United States, or to willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment service of the United States.” The penalties ranged from up to thirty years in prison to death. The enforcement of the Act was left largely to the U.S. Attorney General, but an ample amount of authority went to the Postmaster General, who could impound or refuse to forward through the mail any publication that violated the statute. The Act stopped short of censorship of the press, although Wilson believed that censorship of the press should have been included, and said so as he signed it. The Act was amended several times after passage, but the most significant amendment was the Sedition Act of 1918. In the year that followed the Espionage Act, it became apparent that the stringent restrictions to free speech would be difficult to enforce, as wartime violence by various groups arose pitting an attempt by one faction of the population to suppress the free speech of another by taking the law into their own hands. Therefore, the Sedition Act was passed as a virtual amendment to the Espionage Act and forbade “the use of disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the United States government, its flag, or its armed forces or that caused others to view the American government or its institutions with contempt.” This amendment amounted to a vicious assault on the principles of free speech. However, owing to the fact that the war was nearly over when the virtual amendment was passed, there were few prosecutions in its duration, and it was repealed December 13, 1920.

The “Clear and Present Danger” Test: Needless-to-say the law went through many court decisions and a number of them made it to the Supreme Court upon appeal. Prior to the year 1900 most restrictions on free speech were created as a matter of prior restraint, or prohibition in advance. The test the courts generally used at the time was known as the “bad tendency” test, meaning that the speech had the sole tendency to incite or cause illegal activity. In a landmark case, Schenck vs United States, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. in writing the unanimous opinion said that by distributing flyers to draft aged men to refuse induction, Schenck and others, were not protected by the First Amendment free speech rights as their actions were in direct violation of the Espionage Act. In this process Holmes also created what became known as the “clear and present danger” test to be applied to outlawed speech by stating that “the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” The difference arises in that the defendant’s actions took place during wartime and not during more normal times of peace. Holmes and fellow Justice Louis Brandeis dissented in the case of Abrams vs United States, as they believed that the clear and present danger test was not properly applied. But for many years it was used in free speech cases and became the standard until the case of Brandenburg vs Ohio in 1969. Brandenburg was a Ku Klux Klan leader in Ohio who in 1964 invited a newspaper reporter to a rally where incendiary speeches were made about the forced deportation of black Americans and Jews among others. The court ruled that the government cannot punish inflammatory speech unless the speech is “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” In that nothing directly came of the threats, the court overturned Brandenburg’s arrest and conviction in Ohio and the words “imminent lawless action” supplanted “clear and present danger” as the vital test of freedom of speech.

⇒ Read the entire article on the dmcelleyauthor.com website here:

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.