The American Woman Who Reported on Japan’s Entry Into World War I

Published: 8 August 2023

By Diana Parsell

Special to the Doughboy Foundation website

Scidmore_ERS_PhotoShootJapan

A woman thought to be Eliza Scidmore, at a photo shoot in Japan. (National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Archives)

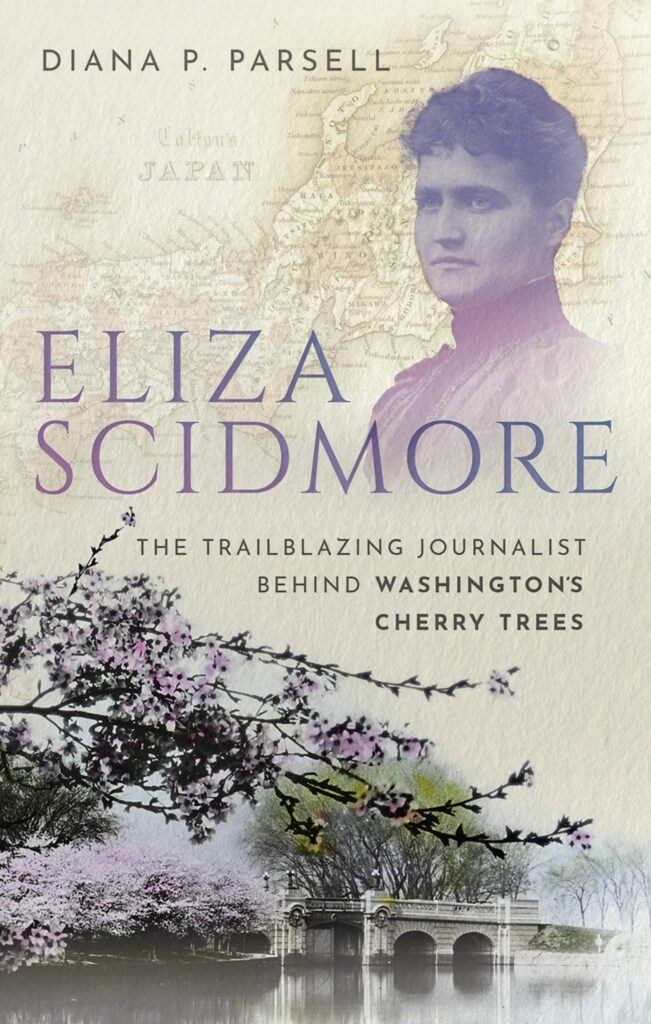

Journalist Eliza Scidmore was also the visionary behind Washington, DC’s famous cherry trees.

Eliza Scidmore, an American journalist and travel writer, was in Yokohama in the summer of 1914 when World War I broke out. Though the United States vowed to remain neutral, Japan joined almost at once. In late August, Japan became a partner of Great Britain and the Allies to help route German battleships from Pacific waters.

Scidmore hustled to write about the developments for The Outlook, an American magazine.[1] Her December 23 article describes the lead-up to Japan’s entry into the war and its early military operations.

Nearly sixty at the time, Scidmore was still splitting her time between America and Asia. For three decades her brother’s U.S. consular work had given her a part-time home in Japan, and a base for reporting on people and places across the region.

Nearly sixty at the time, Scidmore was still splitting her time between America and Asia. For three decades her brother’s U.S. consular work had given her a part-time home in Japan, and a base for reporting on people and places across the region.

Her published work included hundreds of newspaper and magazine articles; popular books on Alaska, Japan, Java, China and India; and a novel based on her visits to POW camps in Japan during the Russo-Japanese War. For twenty-five years she was closely affiliated with National Geographic as a writer, photographer and its first female board member.

Over the years Scidmore developed a deep affection and admiration for Japan and its people. Her best-known book, Jinrikisha Days in Japan (1891), made her a well-respected interpreter of Japanese affairs during the Meiji period, when the tiny Asian country was modernizing itself at every level of society to become an equal of the great “civilized” countries of the West.

I first stumbled onto Scidmore years ago through her 1897 travelogue Java, the Garden of the East, which I read after living in Indonesia. In an online search of the author, I was stunned to discover that she was the earliest champion of Japanese cherry blossoms in Washington, D.C. I had lived in the D.C. area for ages and went every year to see the trees in bloom. Yet I had never heard of Scidmore. So began my decade-long project to write her biography, published in March 2023 by Oxford University Press.[2]

Scidmore’s 1914 Outlook article turned up during my research. It’s reprinted in Elizabeth Foxwell’s In Their Own Words, an anthology of writings by women who served in World War I.[3] In contrast to her usual travel and cultural stories, the article has a strong editorial slant that clearly reveals her sympathies toward Japan. Despite the obvious biases, the piece offers a fascinating closeup look at an early, little-known phase of World War I that took place in the Pacific, far from the main events in Europe.

Soon after declaring war on Germany on August 23, Japan mobilized its navy and began seizing German-held territory in the region. The operations included what became a highly controversial move. That fall, Japanese-led forces invaded China’s coastal Shantung Peninsula and mounted a two-month siege that forced the surrender of Tsingtao, a seaport leased by the Germans.

Diana Parsell

Japan’s actions made Americans uneasy. Long-friendly relations had grown strained in recent years amid growing fears about Japan’s military might and imperialistic ambitions. Japan went to war against China in 1894-5, then Russia in 1904-5. Its shocking victories in both conflicts altered the balance of power in East Asia and made Japan a major player on the world’s geopolitical stage.

Japan’s expansionist aims in China were well known. Now, observers asked, did Japan enter the unfolding conflict in Europe and seize Shantung—an apparent flouting of the U.S.-brokered “open-door” policy in China—as part of a strategy to draw America into a war over supremacy in the Pacific?

Scidmore dismissed the concerns in a robust defense of Japan’s integrity and honorable intentions. Japan entered the war “deliberately, [but] reluctantly,” she wrote. Most Japanese dreaded the entanglement. They were tired of war and saw no need for their young men to die for a European cause. Nor did they harbor any real animosity toward Germans, whose institutions inspired many of the reforms Japan adopted in its sweeping program of modernization.

Japan got involved, she explained, out of its obligations under a decade-old defense alliance with Great Britain. As for the seizure of Shantung, it was “a duty, and it was performed with thoroughness and efficiency,” as well as in accordance with Hague conventions. Japan promised to return Shantung to China after the war.

With Japan proving itself a strong and loyal ally in the broader war game involving European countries, she wrote vehemently, “let us hope that we have been done with those senseless catch-words ‘the Yellow Peril.’ ”

Ensuing events made her faith in Japan and its good intentions seem naive. As scholars would reveal, Japan had jumped quickly into the war as an opportunity to acquire former German possessions and expand its empire.

Eliza Scidmore

That winter, only a few weeks after Scidmore’s Outlook article appeared, news leaked that Japan had secretly issued an ultimatum to China. The so-called Twenty-One Demands called for territorial concessions and special privileges in Shantung and other areas that would give Japan enormous control over China. In the face of protests by the United States and other countries, Japan moderated its demands. But the damage was done. Though Japan would remain a partner of the Allies, the incident provoked ill-will and mistrust that would linger for years.

As Patricia O’Toole writes in The Moralist, her biography of Woodrow Wilson, the question of returning Shantung to China later surfaced as one of the thorniest diplomatic issues in final negotiations at the Paris peace talks in 1919.[4] Among the fallout, she notes, the ultimate decision in Japan’s favor marked China’s break with the United States and the West.

Back in Washington, Scidmore’s other writing during the war included publicizing the work of the Red Cross. After the United States entered the war in 1917, she went to Europe to report on relief efforts in Switzerland and France.[5] To do her patriotic duty at home, she joined the women’s section of the Navy League in Washington to train for national service and went to work in the paymaster general’s office.

Deeply humanistic in her outlook, Scidmore had long approached her journalistic work from a belief that people of different cultures could get along if only they understood one better. George Washington University recognized her contributions in that regard by awarding her, in the spring of 1919, an honorary doctorate of letters for her “sympathetic interpretation” of countries in the Far East.

Having witnessed the tragic effects of war on three continents during her lifetime, she became an ardent advocate of the League of Nations. An international body to promote lasting peace and world order seemed a hopeful development for humanity.

When personal circumstances prompted Scidmore to seek a new home abroad late in life, she settled in Geneva, Switzerland. Her letters to friends and family, up until her death in 1928, are full of lively, opinionated observations of League affairs, as well as sorrowful resignation over the political and social turmoil of the post-war world. Her letters make clear that she never overcame her disappointment at America’s failure to join the League.

###

[1] Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, “Japan’s Platonic War with Germany,” The Outlook (December 23, 1914). [link: https://archive.org/details/sim_new-outlook_1914-12-23/page/914/mode/2up] [2] Diana P. Parsell, Eliza Scidmore: The Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington’s Cherry Trees (March 2013, Oxford University Press). [link: https://dianaparsell.com/books/eliza-scidmore/] [3] Elizabeth Foxwell, ed., In Their Own Words: American Woman in World War I (Oconee Spirit Press, 2015). [link: https://www.worldwar1centennial.org/index.php/communicate/press-media/wwi-centennial-news/6002-podcast-foxwell-interview.html] [4] Patricia O’Toole, The Moralist: Woodrow Wilson and the World He Made (Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 2018), pp. 384-7. [5] Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, “Stories of the Internés: I—Hospitable Switzerland, Outlook, Dec. 5, 1917; “In the Wind-Swept Marne Country,” Outlook, June 26, 1918.External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.