The 72-Year-Old Who Lied About His Age to Fight in World War I

Published: 2 June 2023

By Nick Yetto

via the Smithsonian Magazine web site

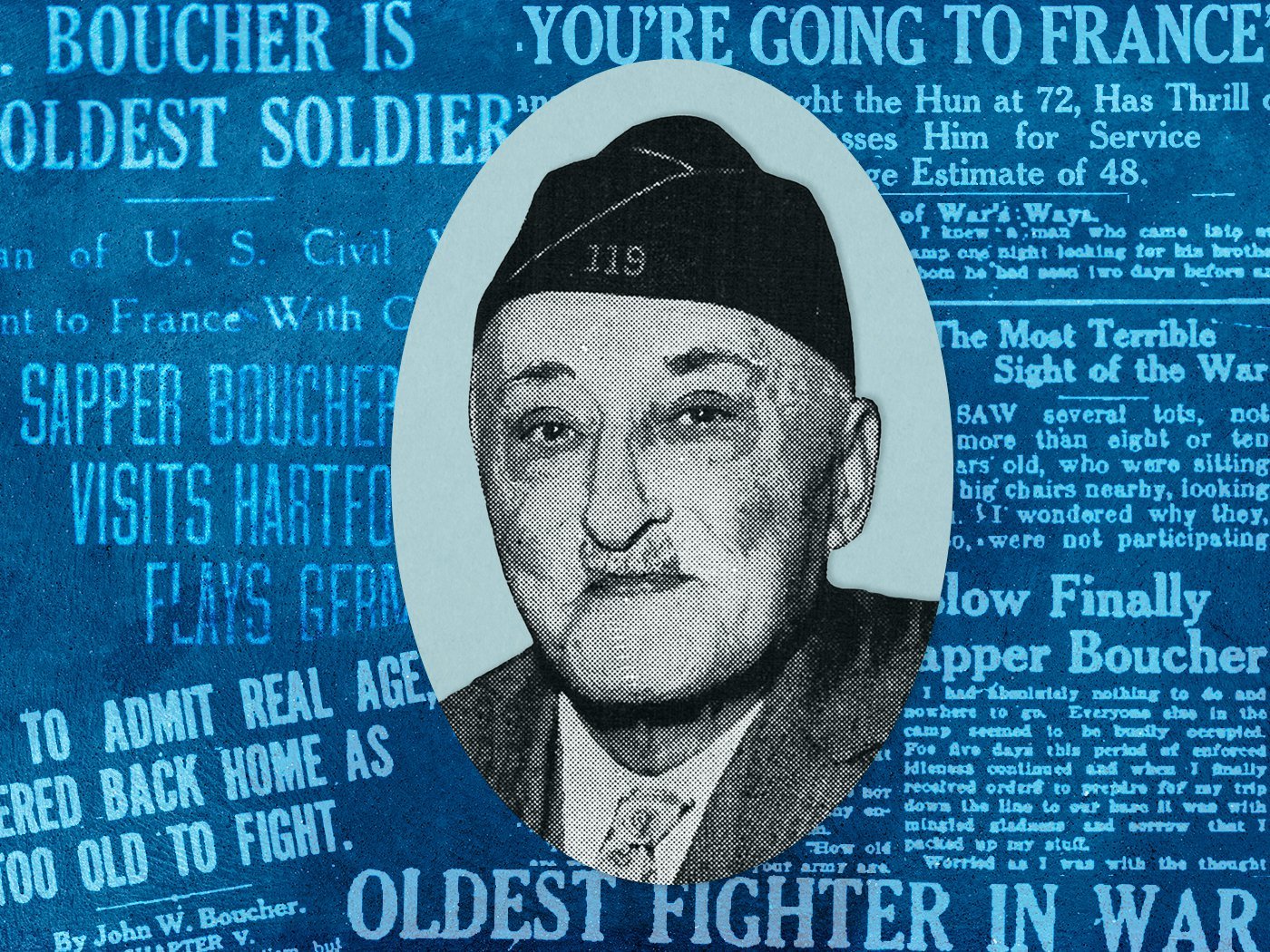

boucher

A Civil War veteran, John William Boucher was one of the oldest men on the ground during the Great War

John William Boucher served honorably in the Civil War, fighting for the Union for seven months in 1864 and 1865. For most men, that would have been enough. But Boucher picked up his rifle again 52 years after the conflict’s end, when, at age 72, he became one of the oldest—possibly the very oldest—men to serve on the battlefield during World War I.

Boucher was born in Ontario, Canada, in December 1844, when Canada was still a British colony. Boucher’s parents were proud subjects of the crown. After his father’s untimely death, likely around 1850, Boucher was sent to boarding school. When the Civil War broke out, he dropped his books; slipped across the border; and, at age 19, tried to enlist in the Union Army. “I had gone out of my way … to battle for the cause of freedom in America’s Civil War,” wrote Boucher for the Syracuse Post-Standard in 1918.

Interestingly, Boucher’s Canadian citizenship wasn’t as much of an impediment to enlistment as his youth. Between 35,000 and 50,000 Canadians served in the Civil War, most on the Union side, even though it was technically illegal for British subjects to serve in the conflict. No driver’s licenses or formal identification cards existed at the time, so paperwork pretty much ran on the honor system. To the military, a body was a body.

Illustration of the Battle of Nashville, which took place in December 1864

From the archival record, it seems that Boucher first tried to enlist in Buffalo, where he was deemed too young, then in Cleveland, where he was rejected for causes unknown. He was finally accepted in Detroit, where he joined the 24th Michigan Infantry. He claimed to have served at the Battle of Nashville in December 1864 and through to the war’s end in April 1865.

A John Boucher appears in the 24th’s roster, but some of the details seem off. For one, the Boucher who enlisted in Detroit in September 1864 and was discharged in Jackson, Michigan, on October 26, 1864, was 18 at the time. In September 1864, Boucher would have been 19. If this roster is accurate, he served 56 days of active duty at most. The Battle of Nashville occurred 55 days after the listed discharge.

“Record-keeping then was not what it is now,” says historian John Boyko, author of Blood and Daring: How Canada Fought the American Civil War and Forged a Nation, and records kept weren’t always accurate.

After the Civil War, Boucher returned to Canada and started a family. He worked as a surveyor, baggageman and freight conductor for multiple railroads, even serving a stint stateside. Eventually, he settled in Gananoque, Ontario, on the northern banks of the St. Lawrence River, eight miles from the New York border. Boucher seems to have spent his middle years working in a carriage factory and as a night watchman for a metal foundry. At one point, according to a report in the Windsor Star, Boucher became a guide on the St. Lawrence. “In this work he obtained his first international reputation,” wrote journalist Dunn O’Hara in 1918, “for, as everyone knows, all good fishermen go to Gananoque sooner or later.”

Boucher’s children grew up, and, around 1898, his wife died. By August 1914, Boucher was a 69-year-old widower, healthy and seemingly content, spending most of his days behind a fishing pole. Then Germany marched on Belgium.

“The transformation came to Canada overnight,” wrote Boucher in a series of articles published by the Post-Standard in April 1918. Though Canada had technically been a self-governing dominion since 1867, it was still functionally under British rule. The Commonwealth was in peril, and 620,000 Canadians answered the call to serve in Europe. “The little peaceful fishing town … where I had lived for many years became an armed camp,” Boucher noted. “I saw youngsters … whom I had later taken out on camping and fishing trips suddenly grow to sturdy manhood. … The uniform had transformed them.” Then, he added, “came the inspiration. My place was among them.”

Armies don’t take 72-year-olds—that is, unless the enlistee lies.

Read the entire article on the Smithsonian Magazine web site.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.