Silver Star Medal for Lieutenant (nurse) Elizabeth Dorothy Sandelius Army Nurse Corps, World War One

Published: 12 August 2025

By Edward E. Saunders, LTC, USA (Ret.)

Special to the Doughboy Foundation website

Sandelius, Elizabeth Sitting at Left BW

Elizabeth Sandelius, seated at left.

In dusty archives of the Montana state library a lone military historian, an Army combat veteran, pieced together a remarkable, unheralded, and compelling story of a courageous young Montana woman: a uniformed World War One angel of mercy and a sister-in-arms.

A true daughter of Montana, Elizabeth Dorothy Sandelius was born in 1893 to Swedish immigrants in Cokedale, a gritty Montana mining town in a scenic mountain valley. Over 100 brick smoke-belching coke ovens choked and polluted that valley, day and night, beneath towering, majestic mountains. Here Montana was a scenic, but hard place where life’s mistakes and injuries could kill at random. Over a century ago death was common here, where vast wind-swept prairies and fierce mountain ranges scattered what few doctors and nurses Montana had.

Growing up in hard times and in a demanding place did not seem to dampen Elizabeth’s spirit. Her delightful, almost playful smile and engaging eyes would brighten any day. Elizabeth was a handsome young woman of midsize proportions. Her short hair looked progressive for the time. But she had another look about her—a look of resolve.

At the turn of the twentieth century in Montana, women had few professional opportunities. One was nursing. Elizabeth entered St. Joseph Hospital’s School of Nursing in Helena: Montana’s state capital. She graduated in 1914 as Montana’s 265th registered nurse. She began her nursing career in the small Yellowstone River town of Columbus, Montana.

Distant war drums sounded in 1917. America’s war effort needed nurses. At the beginning of World War One, Montana had more registered nurses [over 500] than the entire US Army Nurse Corps [400]. The Army surgeon general, Merritt Ireland, estimated he would need about 23,000 nurses in France: This was forty percent of all America’s available Red Cross nurses. He would get about one-third of the nurses he needed.

At the beginning of World War One, or the Great War as it was called then, Elizabeth, a Red Cross nurse, volunteered for the Army Nurse Corps. Her fiancé, Ceborn Benbow, volunteered for Army Signal Corps pilot training at Mather Field near Sacramento, California. Not knowing if they would ever see one another again, two weeks before Elizabeth was to leave for war, they quietly married in Montana. And it had to be quiet, as the Army Nurse Corps at that time would not accept married nurses, or nurses with children.

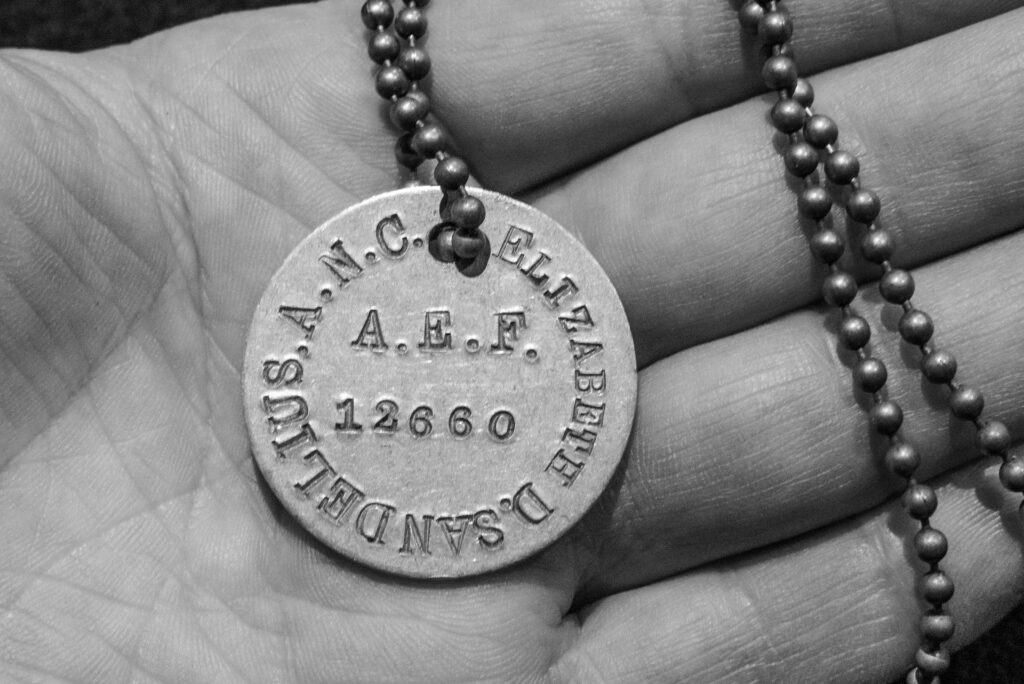

Elizabeth never told the Army she was married. In all her official military papers and on her round Army identification dog-tags she is listed as Elizabeth D. Sandelius, American Expeditionary Force number 12660.

America’s military nurses in World War One were always desperately short-handed and worked to exhaustion wherever they were assigned. The Army first sent twenty-five-year-old Elizabeth to the military hospital at Fort Riley, Kansas. At Fort Riley about 250 nurses, including Elizabeth, cared for over 30,000 recruits.

Elizabeth served at Fort Riley for about six months and then volunteered to go to France. The Army did not require nurses to go into harm’s way; the nurses volunteered for combat duty. [Montana had one of America’s highest per capita percentages of Red Cross nurses volunteering for overseas combat duty.]

This small-town Montana girl then found herself in New York City preparing to sail overseas. In volunteering for overseas combat duty, the nurses would receive ten extra dollars per month added to their fifty dollars monthly pay, the same as a senior sergeant. In Montana nurses could earn over twice that.

In June of 1918 Elizabeth, along with 100 other nurses [five from Montana], sailed to England on the SS Missanabie through enemy submarine-infested waters. Three months after she arrived in England, German U-boats sank the Missanabie off the coast of Ireland.

In France the American Expeditionary Force in France assigned nurses to where the need was greatest. Elizabeth in France nursed in several Army base hospitals and at least in one tented field hospital on the front lines: a M*A*S*H unit of its day.

In July and August of 1918, Germans attacked in force in the Second Battle of the Marne and the Oise-Ainse offensive. The US 28th Infantry Division, attached to the French army, faced heavy fighting. The 28th Division suffered over 14,000 casualties.

The 28th Division desperately needed medical help. Elizabeth went forward to the front battle lines to support the 28th Division. She was assigned to the tented Field Hospital 112 near the village of Cohan, France, about sixty miles northeast of Paris on the front battle lines. From July to August 1918, Field Hospital 112 would receive over 5,000 wounded soldiers and perform over 200 surgeries.

In early August the German army began bombarding the town. Field Hospital 112 was caught in the bombardment. On August 10th as German shelling and bombardment increased, the nurses were ordered to withdraw three miles south to safety. Elizabeth could have left but she refused. Why these angels of mercy in war volunteer for hellish conditions remains deep within their hearts. Like many other nurses in war, Elizabeth never said.

For eight consecutive days and nights, Elizabeth stayed and nursed desperately wounded American and allied patients at Field Hospital 112. She endured enemy artillery and aerial bombardment in dire and deadly conditions. In one aerial bombardment two German aircraft bombs landed within fifteen feet of the hospital tents but failed to explode.

The combined French and American forces finally broke the German offensive. In time Elizabeth came off the front battle lines and nursed at other Army hospitals in France. The commanding general, 28th Infantry Division, Major General Charles H. Muir, signed General Orders No. 1, citing Elizabeth for courage and gallantry under fire. This qualified her for the Citation Star, but apparently, she never received it. She also may have received the French Croix de Guerre, but this is not certain.

The war ended and in May of 1919 she sailed home. The nurses were discharged from service in New York City. The nurses went home by themselves without recognition or fanfare. How Elizabeth returned to Montana and reunited with her husband, who also survived the war, is lost to history.

Elizabeth D. Sandelius’ round WWI Army identification dog-tag, with American Expeditionary Force number 12660.

Ceborn and Elizabeth moved to southern California, raised a family, and lived out the rest of their days. Elizabeth died in May of 1983 and is memorialized in Los Angeles National Cemetery not far from the historic cemetery’s towering flagpole.

During America’s celebration of the centennial of World War One, the author, a retired Army lieutenant colonel living in Montana, learned of Elizabeth and her courage under fire. In coordination with her descendants the author researched national and Montana state records for details. He prepared the case for the Silver Star Medal for Sandelius and submitted the case to the Army. In May 2025 the Army agreed and awarded her posthumously the Silver Star Medal.

Elizabeth is now among the first four American servicewomen in American military history, all World War One Army Nurse Corps nurses, to have been awarded the Citation Star, which in 1932 became the Silver Star Medal. Sadly, America has forgotten many of these gallant women who served in a society, which deemed them peripheral.

The greatest tragedy, which can befall an American serviceman or -woman is not that they may be killed-in-action. That is the greatest sacrifice. The greatest tragedy is that they may be forgotten: Forgotten in life and forgotten in death by the same nation they swore an oath to defend, even at the cost of their lives.

In ceremony at Bob Hope Memorial Chapel, Los Angeles National Cemetery, at 10:00 a.m. PDT on September 24, 2025, on behalf of the US Army and a grateful nation, the author will present the Silver Star Medal to the descendants of Elizabeth Dorothy Sandelius. She is forgotten no more. As General of the Armies John J. Pershing, American Expeditionary Force of World War One, said: “Time will not dim the glory of their deeds.”

Source: Saunders, Edward E. Knapsacks and Roses, Montana’s Women Veterans of World War I. Laurel (MT): Saunders, 2018.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.