Robert Frost: Life and War Were Trials by Existence

Published: 31 August 2022

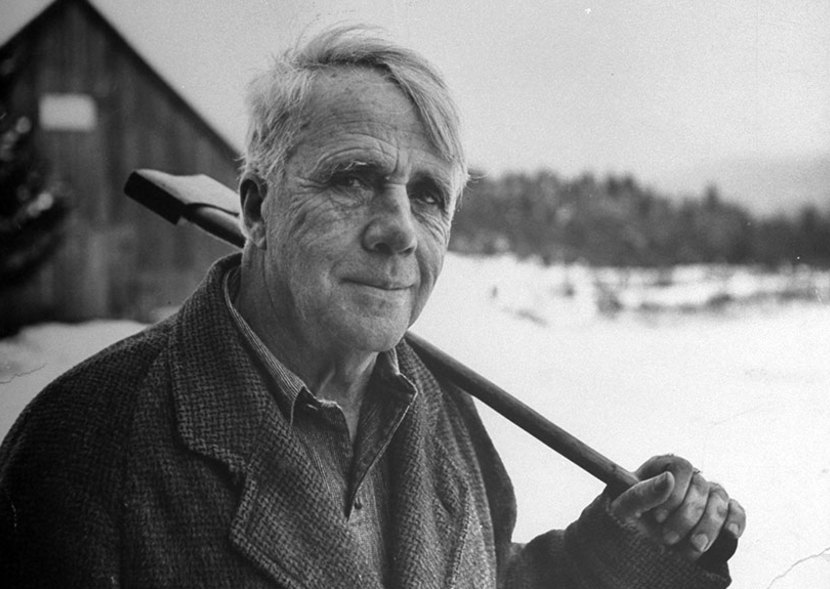

Frostpicture

Robert Frost in 1943. (Eric Schaal/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images). Courtesy https://www.loa.org/writers/271-robert-frost

Robert Frost: A poet for whom life and war were trials by existence

By Jim Dubinsky

When scholars write of war poets, few consider Robert Frost. Certainly, if the definition of a war poet is one who has experienced the turmoil and vicissitudes of combat, Frost does not qualify. However, if one is willing to consider poets who offer insight into connections between war and the human condition, then Frost surely fits the bill.*

Reading Frost’s poems, essays, letters, and gaining insight from a range of biographical perspectives has led me to understand a key component of his personal philosophy: Robert Frost believed in the inevitability of violence. For him, violence and war were natural. He often made statements reflecting this belief. In his private letters to his friend Louis Untermeyer, he argued that “Life is like battle” (285) and “War is the natural state of man” (373).

Louis Untermeyer. Courtesy of https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/louis-untermeyer

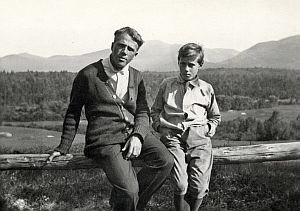

Frost expressed these ideas in response to what he experienced, personally as a husband, father, friend, and artist, as well as what he saw as an individual who lived through both World Wars, the Korean conflict, and the Cold War. They impacted how he understood and framed decisions those close to him made, to include his son’s suicide, as I will explain later.

Robert Frost with son, Carol, who later committed suicide. Courtesy http://frostplace.org/frostcarolmountains/

Named after General Robert E. Lee by his father, a Confederate sympathizer, Frost focused on ideals of gallantry and courage early in his life. In early poems such as “Trial by Existence,” Frost emphasizing the importance of valor, both on earth and “in paradise”:

“Even the bravest that are slain

Shall not dissemble their surprise

On waking to find valor reign

Even as on earth, in paradise.”

This poem was collected in his first volume, A Boy’s Will, which was published, along with his second volume, North of Boston, while he and his family were “living under thatch” in England for two and a half years before World War I broke out.

Even though Frost took his family back to the United States in early 1915, he remained engaged with the war and its issues, particularly through his friendship with the English poet, Edward Thomas, who was killed at the Battle of Arras in 1917.**

Edward Thomas in uniform with the Artists’ Rifles, 1915. Courtesy of http://exhibits.lib.byu.edu/wwi/poets/ArtistsRifles(big).html

In North of Boston, Frost includes a number of poems that address his perspectives on both the human condition and humankind’s proclivity for conflict. Perhaps the most famous statement on human nature comes from “Mending Wall,” a pastoral narrative focusing on a narrator who describes an encounter with a neighbor while out walking his fields.

The poem’s opening lines speak to the violence that attends the change of season from winter to spring. Most poets focus on the beauty and rebirth that accompany this transition. Not so in this poem. Here we open to forces of nature that work to tear down walls:

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it,

And spills the upper boulders in the sun”

The poet shifts focus to signs of spring among humans: hunters and their yelping dogs. The picture Frost paints is one rich with conflict, and the focal point of that conflict is the wall itself, an unnatural but seemingly necessary boundary between neighbors, who are clearly different: “He is all pine and I am apple orchard.”

That difference between the neighbors leads the narrator to imagine a potential result stemming from the difference, an image that is at the heart of the poem: the neighbor as an “old-stone savage armed,” who “moves in darkness.”

This poem, by examining boundaries between neighbors, even those whose only difference is the type of trees on their land (pine vs. apple), delineates an essential conundrum that can be extended to tribes or nations. While on one hand, we often wonder why walls are needed, or as the narrator says, “Before I built a wall I’d ask to know / What I was walling in or walling out, / And to whom I was like to give offence,” in the end, particularly after imagining his neighbor as a “savage armed,” the narrator concludes by explaining why walls are essential: “Good fences make good neighbors.”

Mending Wall by Ken Fiery. Courtesy of https://fineartamerica.com/featured/mending-wall-ken-fiery.html

While “Mending Wall” might be seen as a reflection on the differences between people (and therefore) nations that occasionally lead to conflict, poems such as “The Black Cottage,” also included in North of Boston, focus on the pain and loss caused by war, particularly for those who are not the combatants. Similar to the “Ruined Cottage” by Wordsworth, both poems tell stories of women whose family members go off to war and do not return.

Said Margaret, ‘for I knew it was his hand

That placed it there, and on that very day

By one, a stranger, from my husband sent,

The tidings came that he had joined a troop

Of soldiers going to a distant land.

He left me thus—Poor Man! he had not heart

To take a farewell of me, and he feared

That I should follow with my babes, and sink

Beneath the misery of a soldier’s life.’

This tale did Margaret tell with many tears:

In “The Black Cottage,” the focus is on the American Civil War, and the story is about one who “fell at Gettysburg or Fredericksburg.” The bleakness of the cottage highlights the emptiness of the lives of those left behind, those who strive to make sense of loss they experience, often resorting to pondering the causes that led to the conflict and wishing they were in a “desert” with nothing to “covet” or “think it worth / The pains of conquering to force change on.”

While Frost is not a traditional war poet, he thought and wrote about war, its causes, and its costs, costs he felt deeply and tried to articulate in poems such as “Not to Keep,” first published in the Yale Review in 1917 and later in New Hampshire. This poem focuses on the perspective of a young wife who experiences the joy of having her wounded husband return home to heal, as well as the deep, existential fear of knowing that his stay is temporary.

. . . The same

Grim giving to do over for them both.

She dared no more than ask him with her eyes

How was it with him for a second trial.

And with his eyes he asked her not to ask.

They had given him back to her, but not to keep.

Frost’s poems focused not only on the personal but also on the public. In “A Soldier,” one of several poems in honor of his friend Edward Thomas (another “To E.T.”), Frost creates what is almost a hymn to the anonymous soldier who is portrayed as a

“. . . fallen lance that lies as hurled,

That lies unlifted now, come dew, come rust.”

The soldier as lance, an image out of place in the modern technological warfare of WWI, hearkens back to Frost’s reflections on valor. In this poem, Frost recognizes both the anonymity of the individual soldier, who died by the hundreds of thousands in World War I, as well as the overall uselessness and lack of utility of those deaths with the focus on “unlifted” and “rust.”

soldier on horseback with gas mask and lance. Courtesy of https://www.gettyimages.fr/detail/photo-d’actualit%C3%A9/german-lancer-photo-dactualit%C3%A9/615314368#/german-lancer-picture-id615314368

Medieval meets modern. WWI German

However, perhaps because “A Soldier” is published in 1928 (in the volume West-Running Brook), over a decade after “Not to Keep” first appeared, Frost is able to transcend the personal, taking us from the loss of life to the life of the spirit. The poem, a sonnet, concludes with the immediate discomfort we face as these lances descend to earth and make us “cringe for metal-point on stone.” The poem encourages us see not only how an “obstacle . . . checked / And tripped the body,” but also to see how it “shot the spirit / Further than target ever showed or shone.”

In “A Soldier,” as he does so often in his poetry, Frost offers a duality of perspectives. War brings pain, loss, death, ruin, and rust. But it also provides a means for some eternal worth. And perhaps this poem, though written before his son Carol committed suicide in 1940, offers some clarity to Frost’s comments on that suicide: “ Two things are for sure: he was driven distracted by life and he was perfectly brave. I wish he could have been a soldier and died fighting Germany.”

War poetry is an expansive and not so rigidly-defined sub-genre. No one would or should try to compare Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est”*** Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est” or “Arms and the Boy” or Brian Turner’s **** “At Lowe’s Home Improvement Center” or “The Hurt Locker” with any of the poems I’ve mentioned here. Owen’s and Turner’s poems fall into a separate category. But if we wonder about the conflicts we’ve endured and are enduring, as well as the human costs of and underlying reasons for those conflicts—the “something there is that” sends both ground swells under walls each spring and injured fathers back into battle—Frost’s poems offer perspectives worth considering.****

Robert Frost as a young man. Courtesy ofhttps://www.neh.gov/humanities/2014/mayjune/feature/verse-and-adverse

*I introduced this argument in “War and Rumors of War,” Robert Frost Journal, 5 (1995): 1–22.

** For more on Robert Frost and Edward Thomas, see Connie Ruzich’s Blog, Behind Their Lines, “A Quiet Place Apart”

***For more on Owen, see WWRite article on “Dulce et Decorum Est” by Seth Brady Tucker

**** For more on Brian Turner, see his WWrite post here.

Author’s bio

Jim is a veteran, having served in the US Army on active duty from 1977-1992 and in the US Army Reserves from 1992-2004 before retiring as a lieutenant colonel. His advocacy for veterans and their families has been the impetus for projects including four Veterans in Society (ViS) conferences (2013-2018) and a 2016 National Endowment for the Arts (NEH) Summer Institute on Veterans in American Society held at Virginia Tech.. His commitment to supporting veterans and their families resulted in his becoming a founding member and the first chair of the VT Veterans Caucus.