Private Earl Edward Jones: after 87 years, rosette officially closes his case

Published: 4 July 2022

By Robert Laplander

Managing Director, Doughboy MIA

Doughboy MIA for July 2022

Our MIA of the Month this time around is a little different, as he isn’t actually MIA anymore!

Our MIA of the Month this time around is a little different, as he isn’t actually MIA anymore!

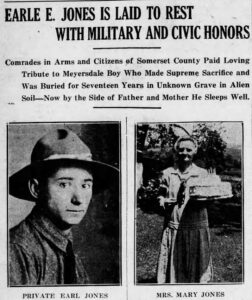

Private Earl Edward Jones was born January 9th, 1894, in Meyersdale Pennsylvania. He was one of the TEN children that William and Mary Jones stocked their household with! His father William died of a stroke in December 1915, so Earl went to work, taking his father’s place as a coal miner in order to help support the family.

On May 31st 1917, Earl joined the Pennsylvania National Guard, figuring it the best way to get overseas faster. He was assigned to Company C of the 10th PA Guard which, upon federalization on July 15th of that year became Company C of the 110th Infantry Regiment, 28th Division, training in part at Camp Hancock, Georgia. With the 110th he sailed for France aboard the City of Calcutta on May 3rd, 1918.

That summer, the 28th was engaged in the fighting around the Fismes sector and the Marne Valley. It was there, on July 15th 1918 – exactly one year to the day that Earl’s unit had entered federal service – that during fighting outside the hamlet of Sauvigny, Earl and several of his comrades were captured. In a statement given to the C company commander, Captain William C. Truxal, by Earl’s corporal, Herbert Jones (no relation) reads: “I helped to carry Private Earl E. Jones across the Marne River after having been taken prisoner. His left leg was blown off below the knee, he was bleeding profusely, and he was unconscious. We put him down on the north side of the river and were not permitted to move him. Later on, one of the men told me that they had buried him in the Marne River.” The burial had been very hurried as the Germans were in no mood to let the Doughboys honor their dead and they were quickly hustled off to a detention location before being sent off to a prison camp. Consequently, the grave went unmarked.

Graves Registration personnel sent out after the war to try and recover Earl’s remains based on the scant information given them by surviving members of his hasty burial were unsuccessful. It had been a brief event, under extremely trying battle circumstances some two years previous, and thus details were sketchy. By and by, without any success at locating his final resting place, Earl’s name was added to the Tablet of the Missing at the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery at Belleau Wood when the cemeteries were officially created by the ABMC. In 1931 Earl’s mother, the widow Mrs. Mary Jones, sailed on the Gold Star Mother’s Pilgrimage that year aboard the President Harding to see his name at the cemetery. She traveled with two other Somerset County Gold Star Mothers as well and while on the return voyage to the States aboard the S.S. America, on the night of August 29th, 1931, commented that her fondest wish would be the return of her boy to Pennsylvania if they ever managed to locate him. Tragically, Mary died of heart disease aboard ship that night; a truly heartbreaking climax to an already mortifyingly sad story.

Then, in mid-December 1934, a set of remains was discovered by a Frenchman in an isolated grave on the right (south) bank of the Marne River about 500 meters southeast of the bridge between Passy-sur-Marne and Sauvigny. The river had swollen briefly during winter rains and when it receded it had washed open the shallow grave along the bank. The exposed remains were identified as being those of an American soldier and the local ABMC officials were duly notified. In January 1935, GRS officials arrived and upon full exhumation and examination an identity tag was found with the remains reading EARL E. JONES 123…. CO. C 110 INF. U.S.A. The remains were then taken to the mortuary at the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery for positive identification and determination of disposition of the remains. In May 1935 it was confirmed that the remains were indeed those of Private Earl Edward Jones SN1239967 and his family was duly notified.

Then, in mid-December 1934, a set of remains was discovered by a Frenchman in an isolated grave on the right (south) bank of the Marne River about 500 meters southeast of the bridge between Passy-sur-Marne and Sauvigny. The river had swollen briefly during winter rains and when it receded it had washed open the shallow grave along the bank. The exposed remains were identified as being those of an American soldier and the local ABMC officials were duly notified. In January 1935, GRS officials arrived and upon full exhumation and examination an identity tag was found with the remains reading EARL E. JONES 123…. CO. C 110 INF. U.S.A. The remains were then taken to the mortuary at the Oise-Aisne American Cemetery for positive identification and determination of disposition of the remains. In May 1935 it was confirmed that the remains were indeed those of Private Earl Edward Jones SN1239967 and his family was duly notified.

That June Earl’s oldest brother Lee, acting as next of kin, wrote the army that he wanted the remains brought back to the States in accordance with the indicated dying wish of their departed mother. On July 25th, 1935, then, Earl Jones left Europe, 17-years after he had arrived, departing from Dunkerque aboard the S.S. McKeesport. He arrived at the Port of Embarkation, Brooklyn on August 9th, 1935, and from there was sent on to Meyersdale, where he was buried in the Union Cemetery there on August 18th, 1935, next to his mother and father. It had cost the army $142.55 to bring him home. Forty-six survivors of Company C/110th who had served with Earl acted as the guard of honor at the funeral, and Captain Truxal gave the eulogy. One of his pallbearers was Corporal Herbert Jones.

The GRS had stopped looking for the missing by the time Earl’s remains turned up. Beginning immediately after the cessation of hostilities, the GRS had made every effort, followed every lead, and traced every clue to locate the missing or identify any unknown set of remains that were found. They truly did an amazing job and should be commended for their efforts. But, at the start of 1933 and continuing through 1934 they were forced to conceded they had done all they could do, and thus – after 16-years of searching – they systematically took one last look at each MIA case before closing each down for good. Today, much of the paperwork associated with the GRS searches after the war and their case files, and in particular the papers concerning the Unknowns buried in American cemeteries in Europe, remain, ironically, MIA. Doughboy MIA volunteers spend a lot of time and effort trying to locate the paperwork we need to be more effective in our job of telling their stories and inching toward possible recovery of those still lost on the battlefield, using modern technology. Your donations make results possible, so when we say we appreciate it, that is exactly what it means – and there ARE results, and Earl Jones’ case is one.

Before the pandemic, one of our researchers (Nancy Schaff) paid a visit to NARA II at College Park, MD and along with a bunch of other stuff, she scanned everything in two long forgotten, non-descript boxes of stray paperwork dealing with burials in France we found. They were just two boxes, nothing special. She was just being her thorough self and there wasn’t much to the stuff… or so we thought! Reefing through the scans last year however we came across papers dealing with three men whose remains were recovered in 1934, but whose names still showed up on the MIA list. Looking into this we found their names had indeed been carved on the Tablets of the Missing, as at the time the carvings were done they were still MIA, but that when they were later located no brass rosettes were ever placed next to their names on the wall. Any time a man is found or a set of remains are identified and his name already adorns a wall, a small brass rosette is placed next to the name to indicate he is no longer missing. (Of course, our fondest wish is that no name should ever be without a rosette!) Now, here we had three names which had inadvertently been denied their rosette – and one of them was Earl Edward Jones! Additionally, an independent researcher whom we have worked with on and off found an additional two names that needed rosettes as well, making five total. These five names were submitted to the ABMC with supporting documentation to show they were deserving of rosettes, and all five cases were duly approved. Thus, today all five sport fresh rosettes!

And so, Earl Edward Jones now has the last little detail of his case accomplished. He is home, with his parents and siblings, in a properly marked grave following a 17-year hiatus in MIA limbo, and now after 87-years his name on the wall in France sports the rosette that officially closes his case.

Want to be part of these cases? You can! Do you have a skill you believe we could use in finding the information we seek? Let us know! But by far the easiest way to help is to donate! Doughboy MIA is a tax deductible, 501(c) 3 non-profit organization. EVERY dime you donate helps us solve these cases, commemorate these men, and keep them from every being lost to history. Donate here: www.ww1cc.org/mia

A man is only missing if he is forgotten.