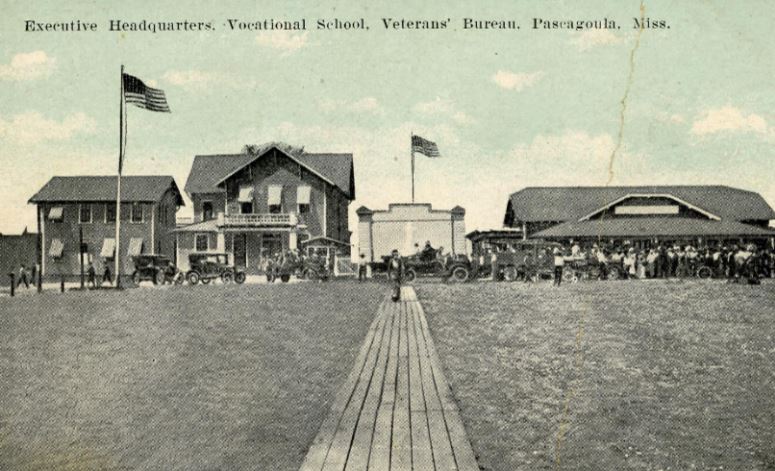

Postcard of Veterans Vocational School after World War I

Published: 27 June 2025

By Jordan McIntire, Historian, Department of Veterans Affairs,

and Jeffrey Seiken, PhD, Historian, Veterans Benefits Administration

via the U.S. Veterans Administration website

Postcard

Postcard of the Veterans Bureau’s vocational school in Pascagoula, Mississippi. In the early 1920s, the bureau operated over a dozen residential schools for disabled Veterans. (da.mdah.ms.gov)

On November 29, 1918, shortly after World War I ended, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed, “This nation has no more solemn obligation than healing the hurts of our wounded and restoring our disabled men to civil life and opportunity.” To fulfill the promise inherent in Wilson’s words, the government adopted a two-step approach to rehabilitating disabled Veterans. Step one entailed medical treatment accompanied by physical and occupational therapy in a hospital setting. Step two occurred on discharge from the hospital and consisted of federally funded vocational training.

The training offered to Great War Veterans assumed many forms, from apprenticeships and instruction in industrial trades to college courses and residential vocational schools run by the government. While varying widely in character, these programs were meant to serve a common purpose: help Veterans overcome their impairments, acquire new occupational skills, and find work. Once a disabled Veteran secured gainful employment, the government considered the person’s rehabilitative journey complete.

Vocational training was one of the benefits promised to service members in the omnibus War Risk Insurance Act passed by Congress in October 1917. The law, however, failed to specify how this training was to be delivered or by whom. At first, the Army’s Medical Department assumed responsibility for both stages of the rehabilitation process, medical and vocational. But the military soon found itself competing with the Federal Board for Vocational Education (FBVE) for control of the second phase. The board was a newcomer to the federal scene. Congress had established it in February 1917 to provide guidance and funding to state-level vocational programs for civilians in agriculture, industry, home economics, and various trades.

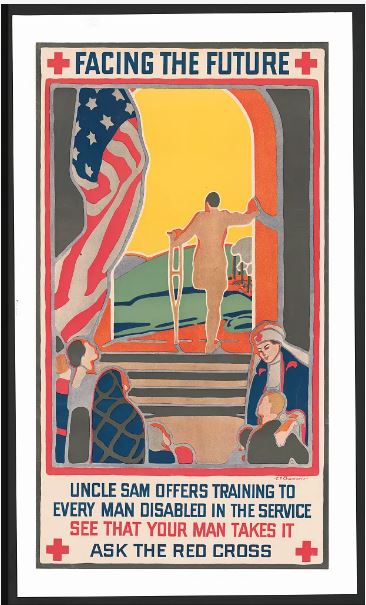

Red Cross poster from 1919 encouraging Great War Veterans to take advantage of government-funded vocational training. More than 100,000 with qualifying disabilities completed training programs from 1918 to 1928. (Library of Congress)

Army medical authorities and their allies in Congress lost their battle with the board. In June 1918, lawmakers approved an FBVE-sponsored bill known as the Smith-Sears or Vocational Rehabilitation Act that placed the board in charge of administering vocational training to disabled Veterans. The law divided Veterans into two categories. Section 2 of the act applied to Veterans with service-connected ailments that prevented them from resuming their pre-war occupations or finding a new one. The government covered the full costs of the training for these claimants and gave them a living stipend for the duration of their vocational program. Section 3 cases referred to Veterans with lesser disabilities who were still interested in pursuing a course of instruction. They were entitled to free training but no stipend. The law also required the board “to provide for the placement of rehabilitated persons” upon completion of their training “in suitable or gainful occupations.”

The FBVE’s lack of experience working with disabled Veterans placed it a disadvantage from the start. The board also possessed next to no institutional capacity in terms of facilities and instructors. Consequently, it had little choice but to rely on the private sector to provide the required training. The board contracted with over 1,600 trade schools, colleges, and other educational institutions. It also partnered with more than 8,000 shops, mills, factories, and businesses.

Its efforts produced very uneven results. Veterans complained that it took months for board officials to respond to inquiries and even longer to get placed in a training program, if at all. In February 1920, the New York Post reported that only 217 of the more than 100,000 Veterans eligible for vocational training had actually finished their programs and found employment through the board. The Post’s expose prompted the House Committee on Education to launch an investigation. The hearings lasted almost two months and brought to light more damning evidence about the board’s inefficiency and ineffectiveness.

→ Read the entire article on the VA website.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.