My Journey to Discover the Author of a World War I Diary, and Tell His Story

Published: 28 August 2023

By Cianna Lee

Special to the Doughboy Foundation web site

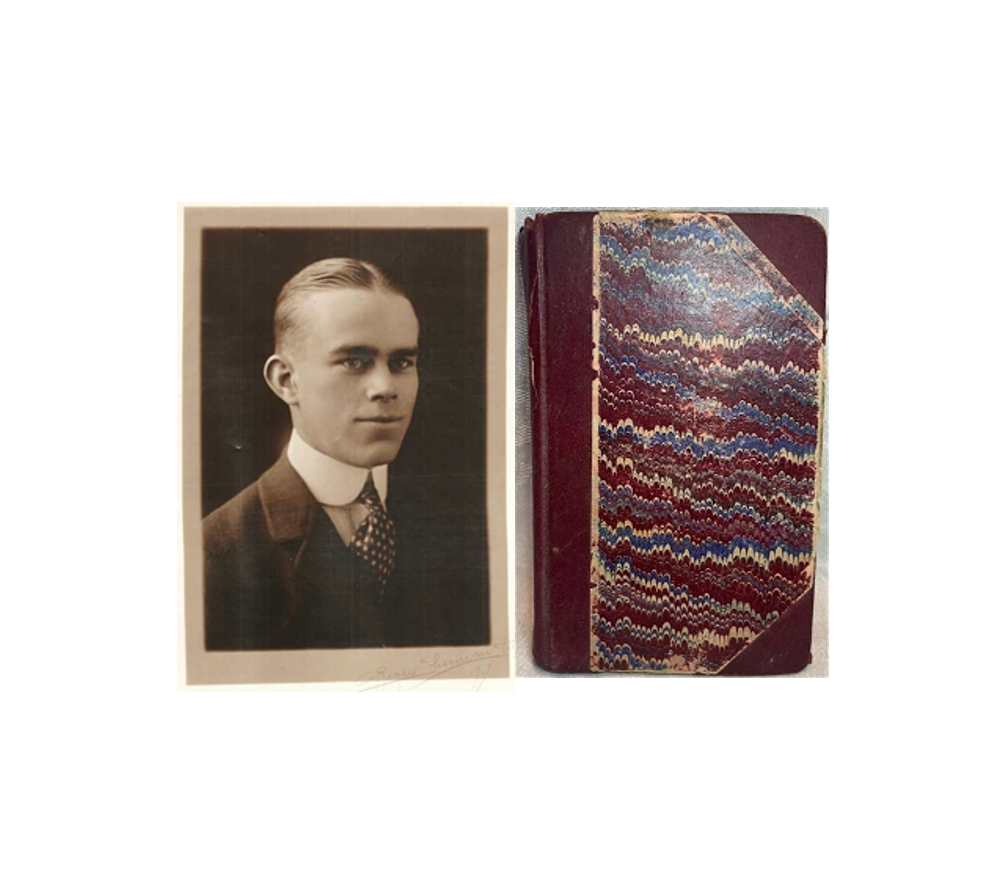

Weeter and Diary

Student sleuth tracks century-old clues to identify author of lost World War I diary

After the school year ended at Bennington College, I found myself with nothing to do. I still wanted to research, so I reached out to a local auction house, Heartfelt Antiques, and Auctions, and asked if they needed any help. Since then I have been researching and pricing books for an upcoming auction.

As I had finished the newer stuff, the owner dug a big tub of random books out of his backlog. Going through the books, I spotted this diary almost immediately. Turning the pages, I realized the diary was about World War I and was written from the war front in 1918. I raced home to inspect and read it. I took pictures of every page written. Remarkably, I realized that the owner had not written his name anywhere on it. I turned these pictures into PDF files and start annotating them.

I had a mystery to solve.

A page from the mystery diary showing the setup of the Yale Mobile Hospital Unit #39 camp at Limoge, France.

I was struck by how good a writer he was, with descriptions of his daily activities, details of what he did with friends, and descriptions of the war from a personal point of view. Many diaries that I had seen in the past mainly noted purchases and day-to-day activities. This personal diary goes into his feelings, the dramas from his unit, and as well as the antics with his friends.

At this point, I only knew that he was an Army private, serving with the American Expeditionary Forces in France. He was in Limoge for 6 months. The entries started on the 9th of April and end on September 12th. I am seeing through a rare window into the daily life of a World War 1 Private, which is so much more personal than a history of the events there at that time.

The next day was July 4th. I spent most of the afternoon reading and annotating as I went through his diary. He mentions that his unit has been renamed the Yale Mobile Hospital Unit # 39. Using that name, I looked up the unit and found out that the unit was featured as part of a museum exhibition about Yale College’s participation in World War I. It turns out that the unit was very innovative at the time, and considered one of the first “M.A.S.H.” Units. It was mainly made up of students from Yale who could not volunteer in other ways due to health or family reasons. There’s a photo from the Maine Historical Society showing that the highest-ranking officer in the unit is named Wells, who he mentions as his commanding officer.

This looked promising, but I still wanted more concrete proof. I found a book with a brief history of the unit, including a sketch of the setup of the hospital camp. This matched up directly with a drawing in the diary. The diarist wrote about the amount of work he had put into setting it up. He was definitely part of this hospital unit. It seemed that Yale has the most comprehensive information on the unit, since the commander, Colonel John Marshall Flint, donated his papers to the college archive.

The more I read the diary, the more I wanted to find out who this person was. The stories he told felt so personal that it felt wrong to mark him at the auction as just some unknown soldier of this unit.

At one point, he even writes:

“I fear this day will ever remain much of a blank. I still don’t remember. Guess I didn’t do anything. Maybe I cut wood, or dug a ditch. Maybe I didn’t do anything. Wonder if there is any record of it anywhere or is it all gone, like a flash of light. I hope all these days are leaving a mark somewhere, because in my life they are wasted – so many taken out of my precious store and thrown away.”

I decided that he deserved to have a name and to be remembered.

The problem was that I had very little experience with WWI documents or military history in general.

I need as much help as I could get.

I emailed the Yale medical archives for more information and asked about a muster roll. I also joined a public chat for WWI military collectors and sellers. I pulled out a few place names from the diary, such as Dead Man’s Hill, and Is-Sur-Tille. He mentioned all of these places frequently; even stating that he was between Souilly and Vertuzey. However, he never said explicitly where he was or when he went to town.

The next day I started looking for WWI museums or institutions that may have more information for me. First I contacted the WWI Centennial Commission to ask about any muster rolls or information they may have. Chris Christopher responded that they didn’t. However, he did find a ship’s manifest on Ancestry.com by using one of the names listed in the Maine Historical Society photo. Going back through what I had read of the diary, I made a list of all the people that the diarist had mentioned and started matching them to the ship’s manifest. Many of his friends went from nicknames and people in passing, to full-fledged portraits of their own. His friends Sam and Morgan and Weeter, all had full names now: Samuel Jerman Keator, Morgan C. Aldrich, and John Lloyd Weeter.

The men and women of Yale Mobile Hospital Unit 39, who sailed for France on Aug. 23, 1917. Joseph Marshall Flint, the unit’s commanding officer and professor of surgery at Yale, is seated at the center of the first row.

A few days later, the Yale Archives scanned the muster roll for me and I printed it out immediately. Then I crossed out every name mentioned in the diary until I had 26 candidates. Throughout an entire day, I went through the Ancestry.com profiles of every single one of the 26 men, Unfortunately, not a single one matched what we knew of diarist.

So back to the drawing board.

I remembered mentions that Agnes (someone he wrote to frequently) had lost Donald Reid, someone very close to her. I assumed Donald was her husband, so I looked for Agnes on Ancestry. The only close match I found was Agnes Reid Weeter whose brother was Donald Reid. The dates for the death matched the diary entries so they were definitely connected. With continued research, I learned that Agnes married John Lloyd Weeter, who was in the diarist’s unit. John Lloyd Weeter also has a brother, Ellis Lobaugh Weeter, who is also mentioned frequently in the diary. I felt like I was honing in on this diarist, and I was going to find him through this John Lloyd Weeter.

I planned a trip to the Archives at Yale Campus and requested all the materials relating to the Yale Mobile Hospital Unit # 39 to be brought to a reading room. I also went back through the tub of books that the diary came in. The name Hattie Towne showed up frequently, and it sounded familiar. When I returned to Weeter’s Ancestry page, I realized Hattie Towne is his mother. This was the most solid connection to Weeter that I have had yet. I decided to do a deep dive on Weeter, but kept running into paywalls with Newspapers.com, so I gave in and signed up for an account.

This was such a good decision. Not only did it give me information on the unit and the people in it, but also gave me a look into their lives. I spent most of a day going through several newspapers looking for information on the unit and all the possible men. I found several other men who were not listed on the muster roll.

That told me there were any number of possible men that I didn’t know about.

Although this was helpful, I still wanted to prove that connection to Weeter. Next, I contacted several people who had Weeter in their family tree. I asked them if they knew about any other member of their family who was in France during WWI. When they responded to me, they told me that the Weeter who is mentioned in the diary so often is probably actually Ellis Weeter, John Lloyd Weeter’s brother. Furthermore, Weeter’s rank in the diary matches Ellis’s rank. One descendant (2nd cousin, 3 times removed) also suggested that the diary might actually be John Lloyd Weeter’s.

I researched more into John Lloyd Weeter’s life through newspapers, Ancestry.com, and FamilySearch.org, I found more and more connections to him in these various sources. That is where I found the concrete link in his FamilySearch profile.

Someone had posted a published letter in the hometown newspaper of his parents about John Lloyd Weeter’s experiences in the war. This mentions an incident that is also described in the diary. The story is incredibly similar, almost word for word, in both the published letter in the newspaper article and in the diary.

Newspaper story about John Lloyd Weeter’s World War I experiences, based on a letter sent home (left) and a page from the mystery diary with matching language.

I have him!

Weeter’s application to join Yale unit.

Doing a deep dive on John Lloyd Weeter – specifically, looking for key dates, his careers, and people he knew I found piles and piles of things, providing me with a match between the diary and those documents. One of the descendants that I contacted on Ancestry also helped me track down names and look through documents.

Finally, it was time to visit Yale, and after a 3-hour drive there, I discovered just how many boxes and documents I had requested. There were boxes and boxes and boxes. After several hours, I found a few things on Weeter. Specifically, his military application, which gave me a little look into his life at the time.

I also found much more information about the unit itself, especially more on how it was mobilized and demobilized. In the diary, it felt like it was a very small group of Yale students who volunteered. However, after looking at the applications, I learned that hundreds of people from campus applied, and even more local nurses. So many people came together to make this unit work and function properly. It was so successful that a second Yale Hospital Unit was mobilized for WWII.

After all this information and searching bland, official reports, I am reminded how much Lloyd Wetter brought that moment in time to life:

“If this unit ever succeeds, and I think we will, it will be because of the men and in spite of the officers.”

With all the information that I have gathered, let me introduce you to John Lloyd Weeter.

John Lloyd Weeter

John Lloyd Weeter was born December 1st, 1893 to John Calvin and Harriet (Towne) Weeter in Salt Lake City, Utah. Lloyd (many records indicate that he most often used his middle name, rather than his first given name, John) was the younger of two brothers, with the other being Ellis. He would have grown up comfortably, amidst his father’s lumber company. He attended Yale and, following his military service, demonstrated an interest in business, as reported in local newspapers at the time. He moved and traveled frequently.

John Lloyd Weeter (seated) with brother Ellis.

He lived in Idaho, and Park City, Utah, and visited his mother Williamstown, Massachusetts frequently. As a teenager, he worked as a mechanic, while also helping with his father’s business. In school, he played several sports, taking a particular shine to baseball. He also loved to sing and performed in church often. He participated in Yale’s R.O.T.C. and Glee Club. In 1917, he applied for the newly created Yale Medical Unit, saying in his application: “My mother wants me to get into some place where I can help but not kill.”

He served (as a private) for over a year in France. In July of 1918, his brother was also sent to France, but as a Lieutenant (Ellis had graduated from the Culver Military Academy and enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania.) He was on the front lines in Argonne Forest. Lloyd was able to take his leave with Ellis for a week and they got to explore France together; however, this was probably the last time that Lloyd would see his brother. Ellis was gassed while serving in France and evacuated back to New York City, where he passed away in November of the same year.

Agnes Reid

John Lloyd Weeter

Lloyd would continue working as an orderly until the armistice when he was finally allowed to leave the war behind him.

In 1919, he would marry Agnes Reid. She was from Baltimore, Maryland, and they probably met through their love of singing. She had graduated from the New England Conservatory of Music. In 1923, they would have a daughter, Ellis – named after his brother.

Lloyd would have had many occupations over the years, mainly working in transportation. Unfortunately, Lloyd would take his own life in February of 1931, in San Diego, California, where he was living at the time. He was 38. His money would go to charity and to Yale, as he had wished.

Agnes would move back to Utah with little Ellis. She would continue to sing through Church, perform as a soloist with the Salt Lake Philharmonic orchestra, and sometimes perform for parties.

All in all, I spent two intense, satisfying weeks looking for a man whose voice came through so strongly about a fascinating time in American history.

You are remembered, Lloyd.

Cianna Lee

Cianna Lee is a rising sophomore at Bennington College in Vermont. Her focus is on history and museum studies, specifically the Victorian Era. Currently, she works as a researcher for Heartfelt Antiques and Auctions. She grew up in the Washington D.C. area but recently moved with her mother to Vermont. In her spare time she loves reuniting historical artifacts with descendants.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.