Music and Entertainment in the Trenches

Published: 5 September 2022

Screen_Shot_2019-03-28_at_3.14.02_AM

British and French troops gather around a “trench cello” at the Battle of Ypres.

Music and Entertainment in the Trenches

British and French troops gather around a “trench cello” at the Battle of Ypres.While music was used for training purposes at home, music making was the most important form of entertainment at the front. Besides the tireless work of the commissioned army song leaders to lead their men in song, independent musical activities sprang across military lines both to combat boredom as soldiers awaited the next bombardment and to divert their minds from the onslaught they were anxiously expecting. Traveling entertainment companies made up of civilians were sent from America’s vibrant vaudeville circuit with the task of entertaining the various regiments.

Musical plays and competitions were organized within each regiment. Welfare organizations such as the Salvation Army and the Y.M.C.A., whose volunteers provided essential services and comfort to the soldiers, also offered singing get-togethers and impromptu concerts held in their tents or “huts.”1 Women dominated the population of volunteers. It is interesting to note the differences and similarities of representation between women at home and women at the front.

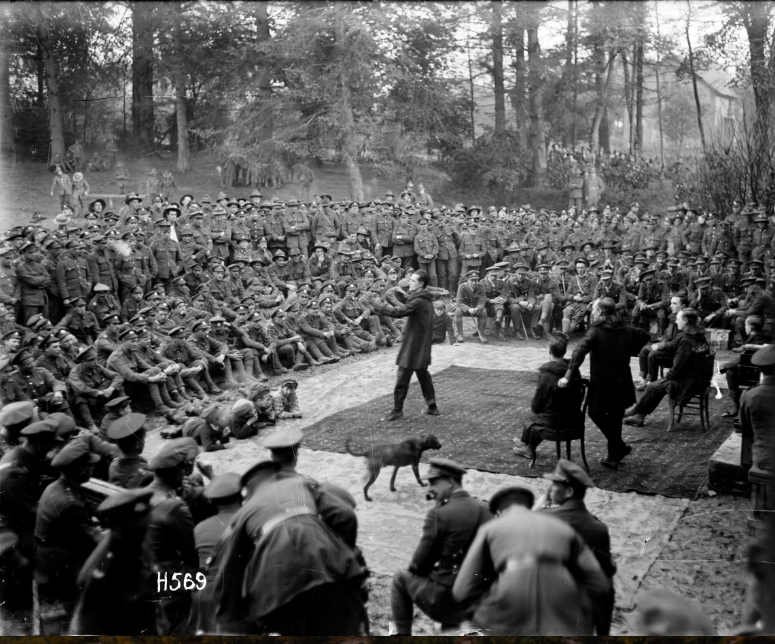

Traveling Entertainment Companies

Veterans of the vaudeville stage back home in the United States were sent to the Western Front to entertain any military unit they found. These entertainment companies often featured a variety of acts. Just like its counterpart, the British music hall, a typical American vaudeville show included song-and-dance acts, comic routines, and acrobatics.2 All acts were sent intact to the front using a pre-planned route. Since their job was to entertain, entertainment companies oftentimes targeted large military units. This led to a congestion of entertainers in a single place thereby leaving out the other troops scattered across different parts of the trenches. It is also interesting to note that the vaudeville genre was a clever way to entertain soldiers in the trenches. First, early variety or vaudeville was designed for men only. Unlike its rival, minstrel shows appealed to both genders. Second, narratives used in these acts were drawn from topics of everyday life. Ranging from immigration to gender roles, the vaudeville act was meant to appeal to wide ranging audiences.3 Putting it in context, vaudeville cleverly made soldiers, regardless of ethnic background, unite in watching or participating in this form of entertainment.

Elsie Janis entertaining the soldiers

Elsie Janis with a group of soldiers

Among the traveling entertainers who went to the front was Elsie Janis. Her versatility as a vaudeville star, singer, and songwriter immediately stood out. Spending six monthsElsie Janis entertaining the soldiers traveling with the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France, she detailed her experiences in a memoir The Big Show: My Six Months with the American Expeditionary Forces. Starting as early as 1914, Janis began singing for British soldiers to boost their morale and as a strong supporter for the Allied cause, she rejected America’s policy of neutrality. When America finally joined the war in 1917, she lost no time in performing her form of patriotism by Elsie Janis with a group of soldiersentertaining soldiers. She recounts in her memoir that she took military entertainment seriously.

I went to my job, which was tiny by comparison, but I often thought if I could put laughter enough into the hearts of our boys, I might also be giving a slap to the Huns. A smiling enemy is much more disconcerting than a frowning one, because you don’t quite know whether he is laughing with you or at you until you come into some dressing-station.4

For the soldiers, Janis was a reminder of women they left behind back home. However, her willingness to support the war and her later accomplishments as an entertainer creates a stark contrast from the passive stereotype women who were often portrayed.5 Janis projected a sense of equal comradeship with the soldiers, a relationship that challenged women’s representation at that time. Her presence in the battlefield showed what a woman can contribute to winning the war at the front. Devoted to the soldiers until the end, her tombstone reads, “Sweetheart of the A.E.F.”

Musical Plays and competitions

Musical plays, oftentimes comic narratives, and competitions were organized by individual regiments to showcase the musical and theatrical talent of their soldiers. Musical comic plays proved to be popular among soldiers. Writing in the Music Supervisors’ Journal in 1920, Russell Morgan reports that

An open air musical play near the front

…each division consisting of nearly 30,000 men was combed for musical and theatrical talent to produce a An open air musical play near the frontmusical comedy, often with play and music written by men within the division.6

Morgan further notes that these plays were performed for each division complete with scenery and lighting. Considering the hard conditions at the front, the amount of creativity these soldiers had to offer to produce an event that included music, script, and design is remarkable. Not content with an ordinary piano to accompany the play, these soldiers arranged pieces intended for a full orchestra. Manned with professional musicians who played in theater orchestras before being drafted into the war, these trench orchestras offered the same kind of entertainment soldiers would have enjoyed back home. Singing competitions were organized by official songleaders who were hired by the War Department. Detailed accounts of these competitions can be found in the monthly newsletter “Music in the Camps.” Check out the PDF copies of the monthly newsletter, “Music in the Camps” in the “Training the Soldiers” menu section.

Welfare Organizations

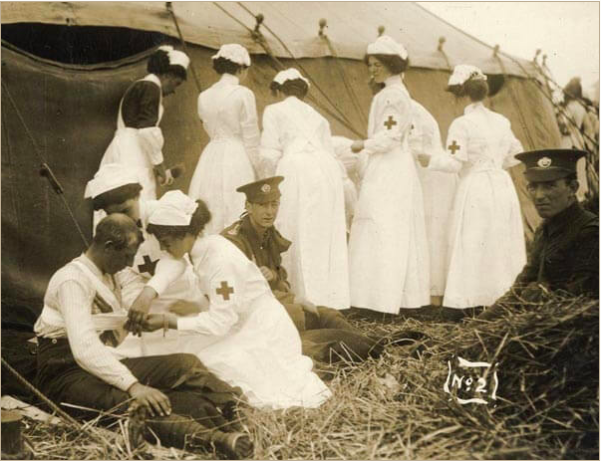

Whether to comfort the wounded or simply to keep the soldiers happy, welfare organizations made up of volunteers such as the American Red Cross, Salvation Army and the Y.M.C.A. furnished their tents or “huts” as they were called with a piano to offer dancing and musical activities. These organizations also hosted concerts for bands, traveling entertainment companies, and musical shows.

A typical Red Cross “hut.”

Amenities in a typical hut contained a large reading room, theater dressing room, kitchen and canteen. A chaplain, barber, and tailor wereA typical Red Cross “hut.” also available. On Sunday, the hut was reorganized to accommodate church services. The service of Mary White Jones, an American Red Cross nurse and hut director tells how she organized theatrical events casting soldiers’ talents, exchanged orchestras and vaudeville acts with other military units, and sing-alongs. Wednesdays were reserved for a dance or show.7 While keeping soldiers’ morale high was the most important goal of Red Cross nurses, their image as the “American Girl” reminded soldiers of home. Red Cross nurse Grace Mary Bell recounts:

I dance my fool head off and grow to like dancing more and more—whatever will I do should I return to dear old Johnson [high school] where no one thinks of me as an “American Girl?” Really, most of us go to about four dances a week! There’s a new order about sending officers to bed at ten o’clock so maybe we’ll keep better hours.8

Another nurse, Margaret MacLaren, also faced challenges in entertaining soldiers.

Of course, you had to dance every night . . . and there were about five girls and about five hundred boys, and you just think nothing of, change partners, change partners, and I danced in . . . what you’d call now, a hunting boot. I wrote my family to send me some heavy, heavy shoes, because they were walking all over our feet.9

Red Cross nurses caring for the wounded.

The efforts of American Red Cross nurses are memorialized in the song “Don’t Forget the Red Cross Nurse” published in 1917. Narrating lyrics Red Cross nurses caring for the wounded.

Working with only few resources and using donuts to remind soldiers of home, female volunteers of the Salvation Army, or “Army Lassies” as they were called, worked tirelessly to provide donuts, religious services, and entertainment for the soldiers. Group singing began with popular songs, but before long, soldiers would ask for hymns that reminded them of home especially mother songs such as “Tell Mother I’ll Be There.”10 Unlike other welfare organizations, the Salvation Army did not have movies or theatrical singing. Instead, they offered meetings in their huts. A typical meeting would last about an hour and a half and they would start out with the “lassies” singing a popular tune followed by a short prayer. Evangeline Booth and Grace Hill, both who served as volunteers for the Salvation Army, describe the meeting:

There was the crowd of men, each uncovered, giving absolute undivided attention to the good, brave girls who were not making a meeting of it; it was just a meeting which grew – men who in their minds were back with mother and sister. The girls sang the good old songs, and then one of them offered a short prayer, in which all the men joined in spirit…11

A Salvation Army “hut”

A Salvation Army “hut”These meetings would begin with popular songs, but the boys would soon ask for the hymns and the meetings would work themselves out without any apparent leading up to it. The boys wanted it. They wanted to hear about religious things.12

Popular songs included “The Long, Long Trail,” “Keep the Home Fires Burning,” “Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit Bag and Smile! Smile! Smile!” and “Keep Your Head Down, Fritzie Boy!” These songs would then be followed by hymns including “Jesus Lover of My Soul,” “When the Roll is Called Up Yonder,” and “Tell Mother I’ll Be There!”13

Besides savoring the donuts that made the Salvation Army popular among the troops, soldiers seemed to enjoy the activities and services that the Lassies had to offer. Just like the American Red cross, the Salvation Army Lassies also had wards to care for wounded soldiers and regardless of setting, music was still the comfort soldiers asked for.

A lassie entered a ward one day and found the men with combs and tissue paper performing an orchestra selection. They apologized for the noise, declaring that they were all crazy about music and that was the only way they could get it.

‘How would you like a phonograph?’ she asked.

‘Oh, Boy! If we only had one! I’ll tell the world we’d like it,’ one declared wistfully.

The phonograph was soon forthcoming and brought much pleasure.14

In tribute for their efforts, popular songs were composed in their memory including “Salvation Lassie of Mine” (1919) and “Goodbye Sally, Good

Verse: Johnny dough-boy was no slow boy “Over there” in France. He never missed a chance to catch ze pretty maidens glance. He’d “oo-la-la” and “parlez vous” with ev’ry girl he’d met. But when it came the day he had to sail away To an “Amry Lassie” I heard Johnny say:

Refrain: Goodbye ‘Sally’ I’m leaving today So long ‘Sally’ I’m sailing away To the land that gave me birth To the greatest place on Earth I’ll tell the folks back home about the “good” you done. We owe a lot to you…

A group of soldiers gather around a piano inside a Y.M.C.A. “hut.”

A group of soldiers gather around a piano inside a Y.M.C.A. “hut.”Besides offering entertainment, the Y.M.C.A. also provided professional coaching sessions to produce plays and musical instruments. More than 200 music directors and coaches were trained and sent to camps at home and overseas. Accompanying them were 1,000,000 song books.15 As a Christian organization, the Music Department was formed as part of the Religious Work Bureau. Thus, songbooks included religious hymns. Though popular songs were also sung in their huts, the Director of Sacred Music made sure that special music was in place for religious services. Music was performed by singers and musicians trained by the Y.M.C.A.’s Entertainment Department16 It is said that they “furnished a total of 4029 musical instruments” along with 450,000 pieces of sheet music and pianos.17

Aside from working in the trenches, the Y.M.C.A. also offered their services in prison camps. Music proved to be the prisoners’ only way to keep their courage. As one prisoner wrote: “Now we can keep our courage, and hold on until the day of peace.”

In need of unity, soldiers turned to music, an entertainment that could be enjoyed by all, an essential need in boosting the morale of soldiers and successfully raising national morale.

Notes:

1. Morgan, p. 24

2. LOC web page “Forms of Variety Theater” https://memory.loc.gov/ammem/vshtml/vsforms.html. Library of Congress. 1996. Accessed March 25, 2019.

3. Ibid.

4. Janis, p. 119

5. In ‘Elsie Janis: “A Comfortable Goofiness,’” Lee Morrow details Janis’ groundbreaking efforts to shed more light on women’s potential to become active participants in society. Facing competing with the male-dominated entertainment industry, Janis “became one of the first women to direct a Broadway musical; one of the first women to write, produce, direct, and star in a motion picture; the first woman to produce a talking picture; the first woman announcer on nationwide radio. She also became a facile contributor to many areas of writing – plays, novels, poetry, songs and lyrics, a comic strip, and a newspaper gossip column.” pp. 151-152.

6. Morgan, p. 24

7. Mary White Jones file, World War I Military Service Records.

8. Bell to Moore, Dec. 27, 1918, Moore papers.

9. MacLaren interview

10. Booth and Hill, p. 92

11. Ibid. p. 250

12. Ibid. p. 257

13. Ibid. p. 247

14. Ibid. p.118

15. Y.M.C.A. Summary, p. 179

16. Ibid., p. 184

17. Ibid., p. 42 18. Ibid., p. 103