How WWI Led to the Apple Watch

Published: 1 September 2022

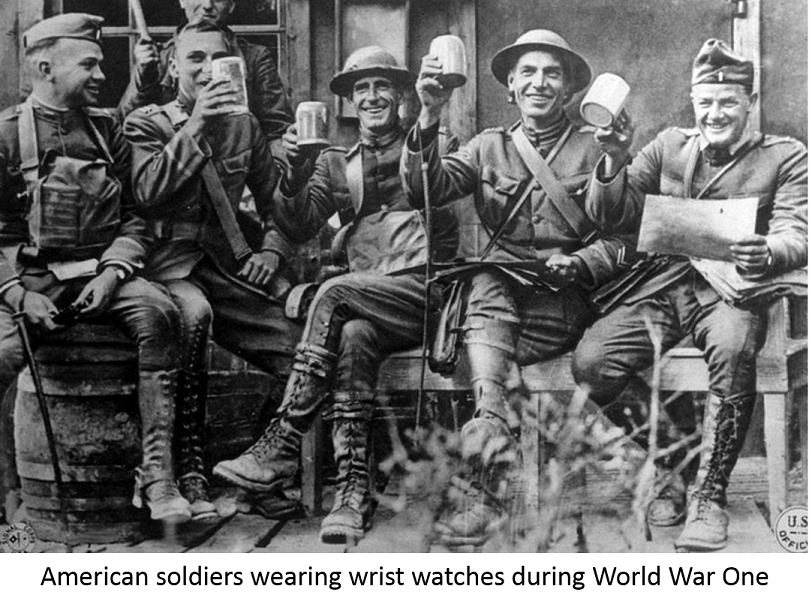

US_soldiers_wearing_wrist_watch_WW1_with_cutline_800

By Christopher Klein

history.com

Yesterday, Apple CEO Tim Cook unveiled his company’s new smartwatch, which will let users make phone calls, read e-mail, surf the web, pay for groceries and even monitor their health right from their wrists. The high-tech Apple Watch, however, may never have come to fruition had World War I not erased the cultural stigma that used to surround wristwatches.

While some credit Swiss watchmaker Abraham-Louis Breguet with designing the first wristwatch in 1810 for Caroline Murat, the younger sister of Napoleon Bonaparte and Queen of Naples, others give the nod to Swiss luxury watch manufacturer Patek Philippe, which developed one for Hungary’s Countess Koscowicz based on an 1868 design. Regardless of the wristwatch’s origins, 19th-century society primarily viewed “bracelet watches” and “wristlets” as dainty, jewel-encrusted baubles to be worn strictly by women for fashion, not practicality.

Into the 1900s, men continued to rely on pocket watches to keep time, although leaders in several countries began to see the wristwatch’s military advantages. In 1880, Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm I ordered 2,000 wristwatches from Swiss watchmaker Girard-Perregaux to assist his naval officers in timing bombardments. The timepieces were also given to a number of soldiers fighting in the Boer War and the Spanish-American War, but at the dawn of the 20th century, wristwatches continued to be seen as “girlish” novelties as impractical as ankle watches.

Fashionable dandies with portable timepieces on their arms were belittled as “wrist-watch boys” while the tried-and-true pocket watch remained the masculine convention. “The fellow who wears a wrist-watch is frequently suspected of having lace on his lingerie, and of braiding his hair at night,” reported the Albuquerque Journal in May 1914. A New Orleans theater in 1916 assured audiences that the main character in one of its plays was not “portrayed by a wrist-watch, screen actor dude, but by a man’s man.”

A century ago, nothing epitomized masculinity more than a good war, and when the Great War itself broke out in 1914, Americans were shocked to find out what the European soldiers were wearing on the battlefield—wristwatches. “It had not been realized before that practically all military men of Europe, privates as well as officers, have given up watch chains and fobs,” reported the Salt Lake Telegram in March 1915.

Soldiers had quickly discovered that the practicalities of the modern warfare ushered in during World War I made the pocket watch obsolete. For one thing, new vest-less uniforms complicated the simple act of carrying a pocket watch, and the ever-quickening pace of warfare precluded soldiers from digging into their coats to remove their timepieces, opening the cases and checking the time. Pocket watches were far too cumbersome and impractical in the new guerilla warfare that required men to be huddled in trenches and crawl through the mud in no-man’s land. With noise often drowning out orders to move, timed signals replaced voice signals. With precision perhaps the difference between life and death, the phrase “synchronize your watches” entered the lexicon as soldiers made mad dashes over the tops of their trenches timed to the exact second hands on their wristwatches, which featured thick metal grills over their glass faces, similar to catcher’s masks, to protect them from shattering.

To soldiers fighting in Europe, wristwatches became as necessary as rifles, and like many fashions in the early 20th century, this one crossed the Atlantic Ocean to the United States. So many American soldiers pursuing Pancho Villa in Mexico in 1916 sought wristwatches that an El Paso, Texas, dealer estimated he sold 25,000 in just two months. Jewelers, drug stores, cigar shops and even fruit dealers in El Paso displayed wristwatches in their front windows. When the Oregonian newspaper suggested in June 1916 that women give their “soldier sweethearts” deployed to Mexico wristwatches as gifts, it assured its readers, “Spoofing? No, no, no. It’s being done.”

The demand only increased when America eventually entered World War I. The first men shipped off to train for war in Kansas City were given a wristwatch and a pound of smoking tobacco as a token of appreciation. Manufacturers such as Longines, Omega, Cartier and Rolex began crafting “trench watches” advertised for military use, and retailers weren’t afraid to prey on the fears of those with loved ones fighting overseas. “The soldier’s most prized possession is his wrist-watch,” proclaimed a 1918 advertisement for an Alabama jeweler because “by its accuracy he advances confidently ‘over the top’ behind the barrage of our own artillery, knowing to the minute the limit of safety in advance.”

When the soldiers returned to the United States after World War I, they brought their wristwatch-wearing habits home with them. The practical benefits of the wristwatch had been demonstrated, and the blood of the war had washed away any lingering feminine connections.

“The war has made the world safe for men who wear wrist-watches,” the Tulsa World proclaimed on April 23, 1919. “A red-blooded masculine person today can appear on the streets, wearing a wrist-watch without the danger of incurring a sneer or a brick. Before the war, the wrist-watch was a badge of effeminacy. The man who affected one was looked on as a fop, a simp or a sissy.” After the war, however, the newspaper reported that “real men wear wrist-watches unashamed.”

Wristwatches became so common that Neil Armstrong even wore one when he became the first man on the moon in 1969. Ironically the advent of smartphones with built-in clocks marked a return to the days when people reached into their pockets to dig out their timekeeping devices. But by bringing computing to people’s wrists, smartwatches such as the Apple Watch may mark a renaissance of the wristwatch, which may never had become fashionable if not for World War I.