How To Tell If A 1918 Trench Knife Is Real

Published: 12 June 2025

By Aleks Nemtcev

via the Noblie Custom Knives website

trench knife framed

Owning a genuine U.S. 1918 Mark I trench knife is more than bragging rights—it is a stake in living history. Every casting flaw in the brass knuckle-duster, every carbon-steel grind mark, and even the particular stale-oil smell of an original leather scabbard whisper about muddy French trenches and close-quarters combat a century ago. A reproduction can mimic the silhouette, but it can’t carry the silent testimony of wartime manufacture, issue, and survival; without that provenance you’re holding a movie prop, not an artifact.

Authenticity also drives market value. A documented LF&C or Au Lion example with untouched patina routinely commands four figures at auction, whereas a modern copy might fetch the price of a steak dinner—before dessert. Collectors, insurers, and estate planners all lean on verifiable traits (maker marks, metallurgy, wartime scabbards) to set valuations; a single incorrect font or newly machined pommel nut can vaporise 90 % of the knife’s worth overnight.

Finally, there is the legal–ethical angle. Many jurisdictions ban or restrict sales of modern “brass-knuckle” weapons but carve out exemptions for bona-fide antiques. If you can’t prove the knife left the factory in 1918, you may find yourself explaining to customs—or worse, to a judge—why you imported a prohibited weapon. Equally, museums and private collections risk reputational damage when reproductions slip into catalogues unchecked. Authenticity, then, is not pedantry; it is the passport that lets the 1918 trench knife travel legitimately between history, value, and the law.

A Brief History of the U.S. 1918 Mark I Trench Knife

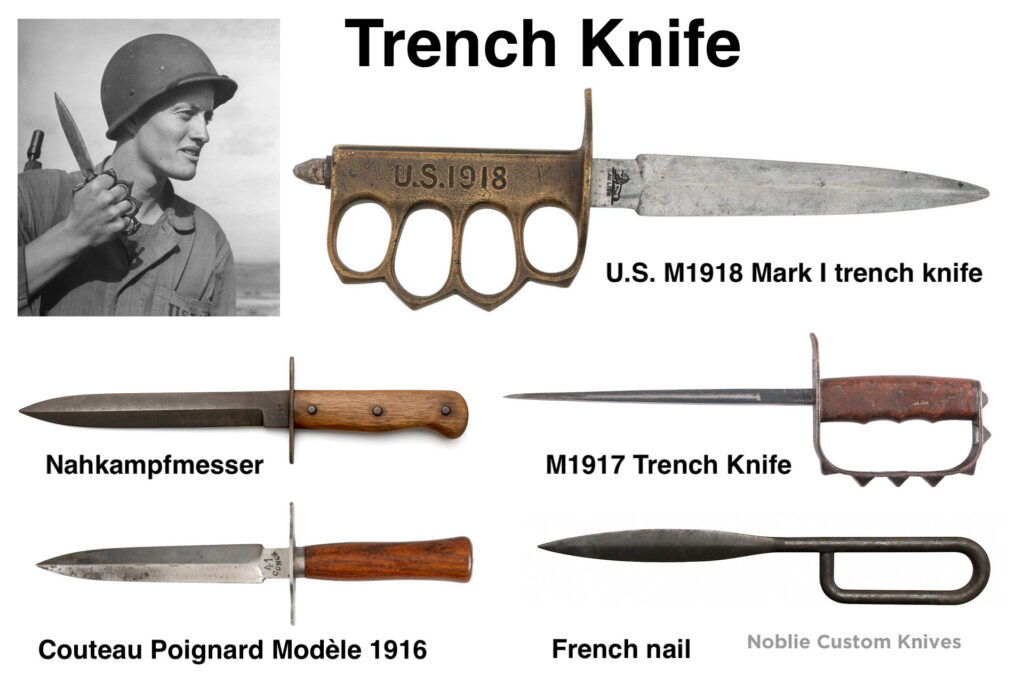

Few weapons illustrate the brutal improvisation of World War I like the U.S. 1918 Mark I trench knife. In 1917, after grim lessons in the mud of the Somme, American planners realised that the standard-issue bolo and bayonet were clumsy inside a sap or dug-out. The first American answer—the M1917 “knuckle-rim” knife—featured a simple cast-iron guard bolted to a triangular stiletto blade, but it shattered almost as often as it struck. Soldiers kept snapping the hilts, then quietly “losing” the knives in favour of homemade weapons fashioned from files and rebar.

When the Ordnance Department went back to the drawing board, officers looked across the Atlantic for inspiration. French assault troops already carried the Au Lion knuckle-duster dagger, a wicked little tool that combined a brass knuckle guard with a slender stiletto. The U.S. design team essentially Americanised that concept—lengthening the handle, beefing up the pommel and specifying a one-piece cast-brass grip threaded for a nut. The resulting pattern, officially adopted in January 1918, became the U.S. 1918 Mark I trench knife.

Production contracts went to three makers: Landers, Frary & Clark (LF&C) in Connecticut, American Cutlery Company in Chicago, and the original French supplier Au Lion. All firms retained the same basic blueprint—seven-inch triangular carbon-steel blade, eight saw-tooth points on the knuckle-guard, skull-crusher pommel and distinctive “U.S. 1918” casting on the grip—but each left subtle fingerprints in font style, nut thread pitch and scabbard hardware. Roughly 120 000 units rolled off the lines before the Armistice halted orders in November 1918.

→ Read the entire article on the Noblie Custom Knives website here:

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.