Horses and Mules

Published: 5 September 2022

Horse_heroes_banner

Horses and Mules

The core, the central focus of these Brooke USA Horse Heroes pages is the animals themselves, the horses and mules who lived and died on the battlefield. In this section those animals will again come alive, as we remember them and appreciate how much their sacrifices meant to the outcome of the war.

“Concerning the war I say nothing…the only thing that wrings my heart and soul is the thought of the horses…oh! my beloved animals…the men…and armies can go to hell but my horses: I walk round and round this room cursing God for allowing dumb brutes to be tortured…let him kill his human beings but…how can he? Oh my horses.” (Sir Edward Elgar, August 25, 1914)1

Horses and mules provided the overwhelming majority of the power used to move men and machines – the true “horsepower” of the war effort. They served in a wide variety of roles, including being ridden, as draft animals pulling vehicles and guns, and as pack animals.

Scroll down to learn about Horses and Mules and how they served. Go to The Mission to learn more about their work as Officer’s Chargers, Cavalry Mounts, and while Pulling and Packing. In all their roles, they were essential to the war effort.

A driver grieves his dead Clydesdales.

Sending animals to war seems, today, somehow even more awful than sending people to war. But in 1914, there was little room for that sentiment. Animals were absolutely essential to the war effort, and they had to be sent – millions and millions of them, by the time the war was over. Most were horses and mules, though dogs, pigeons, camels, and even water buffalo and elephants were also found in some theatres of the war.

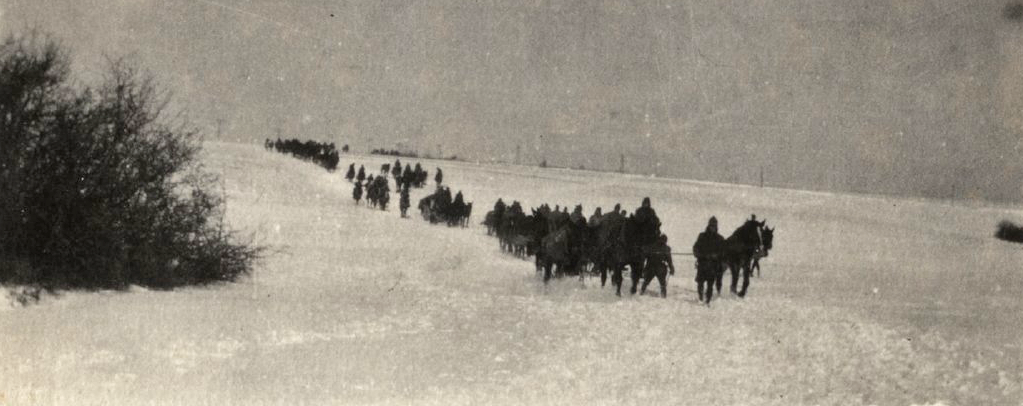

A U.S. Army machine gun company on the way to front, 1918.

A U.S. soldier and his horse wearing their gas masks.

Sources:

- Galtrey, Sidney, Capt., The Horse and The War. Country Life, Tavistock, 1918, p. 35.

- The Tennessean, Nashville, TN, Sunday Sept 12, 1915, p. 49.

- Ibid, Galtrey, p. 43.

- The Quartermaster Review, March/April 1946

- For details on numbers of animals, see By the Numbers

- The Quartermaster Review, September-October 1921, 74, reprinted from The Christian Science Monitor, May 6, 1921, p. 3

- Ibid., Galtrey, p. 43

- Essin, Emmitt M., Shavetails and Bell Sharps, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), p. 153

- ibid., Essin, p. 96

- Notes on Horse Management In the Field, Prepared in the Veterinary Department for General Staff, War Office, 1919 (British War Office publication)

- The Quartermaster Review, September-October 1921, p. 74.

Collection of: National Archives and Records Administration of the United States, Record Group 111: Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, 1860 – 1985

111-H-1192 Historical Films Signal Corps, “Miscellaneous Quartermaster Activities in the A.E.F. (1918)” – Types of horses and mules that were needed in the Army.

War Horse

In this section we look at the animals themselves: how they were selected, what size and conformation were most needed, and which jobs required special attributes.

Horses served primarily in two missions during the war: in harness, pulling guns, supply wagons, and other vehicles; and as saddle horses, for daily use by officers or, on very rare occasions, as the mounts for cavalry soldiers. Learn more about these roles in Under Saddle and In Harness.

U. S. soldiers relax behind the lines. This would be considered a light draft horse.

Qualities that were desirable in military riding horses included smooth gaits, especially at the trot, and the ability to “keep flesh,” that is, a horse that required less than average amounts of feed – what is often known as “a good keeper.”

Horses that tended to put on weight in regular conditions would be very desirable in the battlefield where rations might be short.

Draft horses were further subdivided into the light draft and the heavy draft types.

These were not simply divisions based on size, weight, and pulling power. The light draft horse was also a riding horse, because the guns and in many cases supply wagons were not actually driven by a driver seated on the wagon or gun. Instead, one of the horses in each pair was ridden, and the team was guided by these riders – and at least part of the gun crew had a way to get to the battlefield besides having to walk.

A French light draft horse tied to a pole next to a road. The other horse in the team was killed, and this horse is waiting to be picked up by following troops.

Often it was the animals on the “near” or left side that were ridden, but photos also show the right or “off” side of the team being ridden as well.

So the light draft would ideally have reasonably comfortable gaits as well as moderate pulling power, while the heavy draft horse was not ridden and was expected to excel at pulling heavy loads.

Among the American horses in World War 1, most numerous were the light draft horses (or draught, to use the British spelling, but pronounced the same as the American English word “draft”).

These animals were between 15.2 and 15.3 hands tall1 (a hand being 4 inches, or about the width of a person’s hand), weighing about 1200 lbs., and in their breeding they were likely to have Shire, Clydesdale, Belgian, Normandy, or Percheron blood.2 They were, in body build, somewhere between a saddle horse and a draft horse, and their primary job in the Army was to pull supply wagons and the smaller guns.

Draft horses, in general, are broader in the shoulders than saddle horses, because they actually pull largely with their front legs, leaning their shoulders into the collar or harness, rather than pushing off with their hind legs, as is the case with a ridden horse.

Draft horses may or may not have heavy hindquarters, but ideally have relatively straight shoulders and pasterns3 (that is, nearer to vertical, without as much horizontal angle as some other horses might have). Both the straighter (more upright) shoulder and the more upright pastern would be undesirable in a riding horse, as the gaits of such horses tend to be rougher to ride. But those same characteristics made pulling more efficient and allowed the collar to fit better, without interfering with the horse’s breathing. Draft horses have shorter legs, shorter and heavier necks, and broader chests than saddle horses.

Heavy draft horses pull a big U.S. gun.

The light draft horse would look like a blend between the lighter saddle horse and the heavier draft animal. They would be thick through body and neck, short backed, short legged, and would appear muscular for their size. Certainly the ideal artillery horse, which pulled the guns while being ridden by the gun personnel, would not have extraordinarily straight shoulders and pasterns, because the gunner riding them would be tired from the rough gaits before having to fight.

At the time of World War 1, artillery draft teams were still placed according to size, with the larger horses harnessed closest to the gun and the lighter horses ahead of them. This arrangement of wheelers, swing, and lead horses was eventually replaced with the approach that the best teams were those where all horses were approximately the same size. The traces would therefore lead in a straight line from the rearmost horses to the front ones, and pulling would be most efficient.

The wheelers, whether larger or not, are always working, whether pulling or (in the case of going downhill) resisting the movement of the vehicle, while the lead horses are not so burdened. Thus, if the horses were similar in size, they could be rotated through each of the positions, thus equalizing the work they were asked to do.4

A Signal Corps officer with his horse Bab in Germany, December 1918. Based on color and conformation, this horse is likely a Percheron cross.

The U.S. Great Plains states were the primary source of light draft horses for both the U.S. and British armies, and most probably for the French as well. (Detailed French records are not available showing types purchased, but the French bought nearly as many horses in the U.S. as the British did – about half a million). The Percheron Society of America cooperated with Captain Sidney Galtrey in his book, The Horse and The War, published in Britain in 1918, extolling the virtues of the breed (though much other information was also contained in the volume.)5

With sales topping a million animals by the time the U.S. entered the war, foreign purchases provided a large infusion of cash to mid-western farmers. Galtrey’s description of the American light draught horse as having “hardiness, placidity of temper, strength and power, virility of constitution, with what is called “good heart,” versatility and extraordinary activity for his size and weight”6 were what appealed to army purchasers about this American animal.

Heavy draft horses were similar to their lighter cousins but were at least 1400 to 1500 lbs. Their bloodlines included many of the same draft horse breeds as did the light draft horses, with Shire and Percheron blood predominating.7

The heavy draft horses pulled the largest guns and heaviest supply wagons. One major difference between the light and heavy draft horse would be that the light horse was expected to be able to gallop in harness, while the heavy horse was not expected to go above a trot, and was usually worked at a walk.

At the end of the war, the numbers of animals actually assigned to the AEF was only about half of what should have been assigned based on official supply tables. But the shortages of pack animals seem to be more critical, and point to a failure to anticipate the tasks these animals would have to perform in the particular conditions in France at the time. Trench warfare, with its near-constant circle of supply going forward to a nearby fixed line, may have forced some of the supply work that would ordinarily have been done by wagon to be broken into smaller loads and onto the backs of pack animals.

Sources

- Graham Winton, “Theirs Not To Reason Why, Horsing the British Army 1875-1925.” Helion & Company Ltd., Solihull, 2013, p.436. Often, the personal words of poets, composers, and artists are more likely to be preserved than those of the millions of ordinary, nameless men who wrote to their families. These words came from a letter that English composer Sir Edward Elgar wrote to a friend on August 25, 1914. Elgar was 57 at the time, not serving at the front, but reportedly very depressed about the war.

- Ibid, Galtrey, p. 34.

- Carter, General William H. The Cavalry Horse. The Lyons Press, Guilford, CT 2003. p. 49.

- Ibid, Carter, p. 49.

- Galtrey, Sidney. The Horse and the War. Country Life, London, 1918.

- Ibid, Galtrey, p. 21-22.

- Ibid, Galtrey, p. 34.

Date: 1918

Date: 1918

Mules: The Unsung Heroes Of the War

American humorist Henry W. Shaw (1818-1885), writing under the pen name Josh Billings, wrote this about mules (read phonetically and smile):

The mule is haf hoss and haf Jackass, and then kums tu a full stop, natur diskovering her mistake. Tha weigh more, akordin tu their heft, than enny other kreetur, except a crowbar. Tha kant hear enny quicker, nor further than the hoss, yet their ears are big enuff for snow shoes. You kan trust them with enny one whose life aint worth enny more than the mules.….

Tha haint got enny friends, and will live on huckle berry brush, with an ockasional chanse at Kanada thistels…. If tha ever die tha must kum rite tu life agin, for i never herd noboddy sa “ded mule.” Tha are like sum men, verry korrupt at harte; ive known them tu be good mules for 6 months, just tu git a good chanse to kick sumbody…. Tha kould kick, and bite, tremenjis. I would not sa what I am forced tu sa again the mule, if his birth want an outrage, and man want tu blame for it…..

Tha are the strongest creeturs on earth, and heaviest ackording tu their sise; I herd tell ov one who fell oph from the tow path, on the Eri kanawl, and sunk as soon as he touched bottom, but he kept rite on towing the boat tu the nex stashun, breathing thru his ears, which stuck out ov the water about 2 feet 6 inches; i did’nt see this did, but an auctioneer told me ov it, and i never knew an auctioneer tu lie unless it was absolutely convenient.

By the end of the war, a prominent British general had this to say:

“Great as has been the success of the American gun horse, still greater, though perhaps less appreciated, have been the war qualities of the American mule…probably the most serviceable and satisfactory animal used in the war.” 1— Brigadier-General T.R.F. Bate, British Remount Commission

One book stands out as the final authority on U.S. army mules, Shavetails and Bell Sharps, by Emmett M. Essin.

The Mule In Military Service, by Anthony Clayton, describes the role of the animals in British and imperial era Indian armies.

Since nearly all of the British Remount purchase centers were in the United States, it is safe to assume that the vast majority of these were from the U.S. Mules were purchased via dealers in Missouri and Kansas, and later in the south in Tennessee, Texas, Alabama, and Georgia.

But the south had its own demand for mules, in that most cotton fields were worked by mule power. The price of mules fluctuated greatly during the war, mainly following the price of cotton. Early in the war, British agents paid $175 per animal, and this rose as high as $230 by 1917.

In Nashville, Tennessee, the agent for the British set up an inspection for prospective purchases in September 1915. The Tennessean reported with enthusiasm that this was a great opportunity for everyone in the surrounding area to sell mules, noting that the timing was perfect for farmers to “dispose of them for a good price and not have to feed and winter them in idleness.”

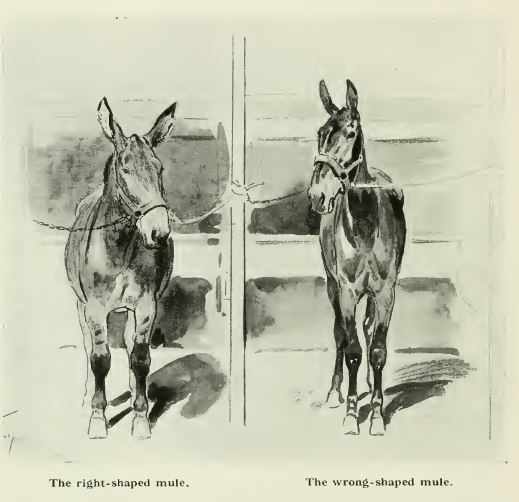

Pack mules were to “have short backs, stand well, and be good boned” with weight proportional to height and conformation, weighing between 800 and 900 pounds and standing 14 to 14.3 hands barefooted.2 Draft mules were to be taller, 15.1 in their bare feet, and should weigh 1000 pounds. It was specifically noted that light gray or white mules were the only ones that would not be considered for purchase. Capt. Sidney Galtrey provided an illustration of what was wanted:3

The spots on the rump of this British pack mule indicate that the mule’s dam was an Appaloosa mare, almost certainly from the American west.

The prejudice against light colored animals had to do with visibility to the enemy. Later, in World War II in Burma, the U.S. Army was reduced to buying any animals that were available, though sending light colored animals to within a few hundred yards of the front was regarded as suicidal for both men and animals. Yankee ingenuity was brought into play and a mixture of water and the common disinfectant potassium permanganate was developed that, when sprayed on a light gray mule, produced a brownish tint that would last for a month or two.4 In WW1, the purchasers simply avoided buying the gray or white animals, though later some were reluctantly accepted from the French.

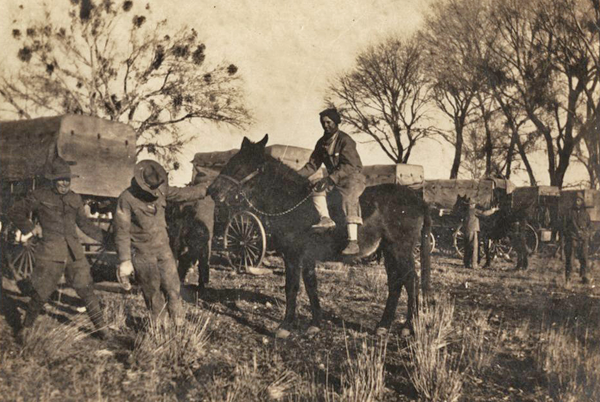

After the U.S. entered the war it had specific standards of height and weight for its mules, and those were different from the British requirements. Wheel mules, that is, those that were harnessed closest to the equipment they were pulling, were the largest. In all animal harnessing arrangements, wheelers pull the most weight; animals harnessed in front pull progressively less. Thus, lead mules were a bit smaller. Pack mules were smaller still, and this was favored because it was easier to lift and lash the heavy loads onto their backs if the animals were not too tall.

| Type | Weight in pounds | Height (in hands, a hand being 4”) | Cost |

| Wheel mules | 1,250 | 15.3 to 16.2 | $230 |

| Lead mules | 1,000 | 15 to 15.3 | $190 |

| Pack mules | 950 to 1,150 | 14.2 to 15.2 | $175 |

Mules hitched to a U.S. supply wagon.

There were 52,137 draft mules and 9,240 pack mules used by the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe, but not all of them came from the U.S. Nine thousand were from France, 16,600 came from Spain, and 6,800 came from England.5 The latter, however, might well have come originally from the U.S.!

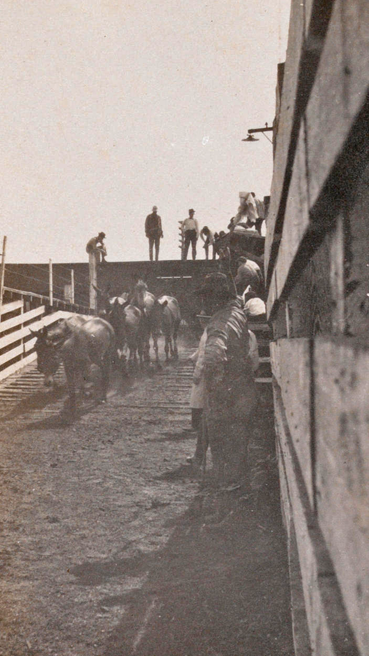

This peculiar state of affairs came about because, after the U.S. entered the war and with limited space available aboard ships sailing from the U.S. to Europe, there was tremendous pressure on American military leaders to get soldiers to the front – with the result that transport of much-needed draft animals was deferred for months. Since the U.S. nominally entered the war in April 1917, but did not actually have many trained troops to send for months thereafter, it was well into 1918 before significant numbers of American troops were present in Europe.

During the first year after the US. entered the war, about 12,300 mules were shipped from the U.S. to France for use by American troops. Several arrangements for getting animals from Allied nations (and thus already in Europe) did not result in nearly enough animals to meet the needs of the U.S. troops. By the summer of 1918 there were such severe shortages of draft animals that another 16,500 mules were shipped to Europe from the U.S., some not arriving until late December – they had been in route when the Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918. Thus, less than 29,000 of the mules used by the U.S. forces actually were brought to Europe with our own forces, and most of those arrived in the last two months of the war. The troops were chronically short of draft animals.

Unloading a mule in Alexandria, Egypt in 1915.

Nearly all the mules used by the British came from the United States (hundreds of thousands), and Italy bought U.S. mules for use as pack animals in their mountain terrain. U.S. mules also went to Egypt to serve with British troops there.

Stories of mulish behavior abounded.

Tales involve mules that kicked or bit overbearing officers but were gentle as kittens with their caretakers, or mules that saved their drivers and themselves by their sure-footedness on impossible terrain, or by continuing on their mission despite being wounded or under severe fire. Mules gained a reputation for intelligence, for not having any patience with incompetent handlers, and for an unerring instinct for self-preservation.

The Quartermaster’s Review provides a story that will make mule lovers smile: “a pack-mule would loaf around the army kitchen when the cook was baking bread until he observed the cook busy at some other duty, when he would approach the fire, raise one foot and paw off the lid of the Dutch oven, grab the hot loaf within and make off with it on the run.”6

French soldiers lead horses loaded with nets full of bread near Verdun.

There are several aspects of this story that are not quite believable: the mule allowed to roam free in camp; the cook preparing bread in a Dutch oven (army mess cooks baked loaves by the thousands in large ovens); and most of all the mule, willing to burn his mouth on a loaf straight from the fire!

But there is an appeal to the story – a smart mule gets the best of a hard-working mess cook! Perhaps it was true, perhaps it really happened not in an army camp but in a mining camp in the American west, and was re-told in France – but most of all, it is endearing, and soldiers in 1918 (and readers 100 years later), wanted to believe it.

In his tribute to the horse and mule in World War I, Captain Sidney Galtrey best sums up the opinion of those who knew mules during the war.

“How can you treat consistently a conglomerate mixture of stolidity, stubbornness, slyness, willingness, temper, sullenness, humour, contentment, waywardness and cunning with no knowledge of which vice or virtue is going to assert itself next.”7

Draft Mules

A mule falls in harness after being injured by shrapnel near Remy, France. His eye shows fear, and perhaps he has broken a hind leg – note the upturned shoe at the bottom of the photo, the leg in a nearly impossible position. The accident must just have happened, since the rest of the team is not yet aware that there is an animal down and is trying to walk forward. Just one tragedy, documented by happenstance, on September 18, 1918.

The chronic shortage of draft animals was a problem for both British and American armies. The American mules which served with British troops early in the war were making a name for themselves as incredibly hard-working animals that could survive on far poorer rations than horses, but, as with horses, the early months of the war proved very difficult for the mules.

British mules mired in a shell hole, Christmas Day 1916. Many times it was simply not possible to get a secure enough hold on the animal to pull it out, and it had to be shot before it drowned. The animal lying sideways on the left is probably already dead, while it may yet be possible to extricate the one on the right.

By early fall 1914, only six months into the fighting, the beginnings of trench warfare were evident – a static line of fighting with almost no advancement, and the land becoming more and more torn apart by constant shelling. Eventually, the repeatedly-repaired roads were the only stable ground that would reliably support the weight of a horse, mule, or cart. Any step off the edge of the road risked the possibility of going into mud several feet deep, or shell holes that held water and mud deep enough to drown animals and men.

A U.S. ammunition wagon holds up an entire supply train on a road near St. Mihiel, France.

In spite of this, going off the roads was often necessary, as the roads were narrow, there was often traffic going in both directions, and a broken-down vehicle could easily block the road completely.

Likewise, the supply lines often went through areas where enemy fire could pick out animals and their handlers. Most of the re-supply work was therefore done at night, without lights, making it even more difficult to stay on stable ground and find the way.

Pack Mules

Pack mules were employed to bring supplies from the rear of the action to the actual front trenches, a distance of several miles. The trenches themselves were elaborate warrens of ditches, with a zig-zag pattern nearest the German lines, and spurs that led back toward supply lines and medical facilities. Pack mules delivered food and ammunition to the ends of the spurs, where they were taken by men and carried to the fighting forces. Further back, the same process was repeated, bringing supplies from trains and trucks to the rear trenches and the stables, hospitals, and kitchens.

There are two main ways to handle pack mules along the road. In the first, pack troopers ride their own mules and the load-bearing animals are herded along as a group. This method is good when relatively short distances are being covered outside the active battle zone. The animals can pick their own pace and footing, leading to less fatigue.

But this method does not work if there are troops on foot in the same column, and it was rarely possible to use this method in France. Mules naturally walk about twice as fast as a foot soldier. Thus, if they are part of a column of troops, or carrying equipment that may be needed quickly, they must be led. Certainly if they are in a battle zone with active shelling possible, there must be a soldier on the end of the lead line, since stampeding panic-stricken mules are a hazard to everyone around them.

Fully loaded pack mule. The well-balanced load is secured with the diamond hitch. Under the load, completely hidden by it, is the pack saddle.

An aspect of the use of mules in army life that not many people would think of 100 years later is the need for expert muleteers (sometimes called mule skinners) who could balance a loaded pack saddle and tie the complex knots required for a pack mule’s load.

The pack saddle itself bore little resemblance to a riding saddle. Though several models had come and gone over the years, the pack saddle favored at the time of World War 1 was the Daly Aparejo Pack saddle, named for Henry W. Daly, who was chief packer for the Army.

Actually more a tightly lashed-together set of small pieces of wood, it formed the base for the load, which was balanced side to side and built up with a series of knots and cross ropes. The saddle was flexible in that it draped over the mule’s back, though it needed to be padded with a blanket underneath in order not to rub the animal raw. Gradually with use, it also began to mold itself to the actual shape of the mule it was being used on, and thus, each mule had its own saddle rather than getting assigned a random one each day.

Well-trained pack mules would, on command, line up in long rows, standing side by side with no lead ropes or other restraint, and with a row of saddles and harness sitting on the ground in front of them – each mule having lined up in front of its own saddle!8

Mules behind their pack saddles in Candelaria, Texas, 1917 or 1918.

Mules that were this well trained were known as “bell sharps,” which referred to their training to follow the sound of a lead mare wearing a bell. All mules naturally defer to horses as their superiors in the pecking order that is found in every herd of equines. Further, they defer to mares as superior to geldings. Thus, the guide for each mule train often rode a mare who wore a bell so that the mules following single file behind could be reassured that she was in fact there whether they could see her or not. If the mare was killed, apparently the mules grieved and were very disconcerted, as they had lost their leader.9

Each troop that used mules also included soldiers whose primary responsibility was to the animals. They loaded them, led them, and took care of them at the beginning and end of every day. If possible, at the end of each day, the animals would be taken out from camp and grazed on lead lines, as fresh grass was the best food for them. If grass was not available, then hay or other forage would be fed. Grain, usually oats, was also fed, and part of the load of each mule was his own food.

Scraping mud off a mule near Bernafay Wood, 1916.

Each animal was supposed to be groomed morning and night, and the army had specific standards and methods for grooming – the muleteers were supposed to take their coats off so they could really put their energy into the task!10 But with the constant mud, army grooming standards were rarely met at least during the winter months.

The constant dampness from autumn through spring made skin diseases an ever-present issue, though mules were far more resistant to them than were the horses. As a defense against lice and other parasites that hid under the body hair of the mules, most animals were clipped, which meant that the winter coats that might have protected them from the elements and kept them warm, were clipped very short.

This did assist in early detection of mange or lice, and in removal of the ever-present mud, but it of course had a very undesirable effect of removing the mule’s natural abilities to keep warm. Thus, they had to be blanketed, but of course, there were often not enough blankets to go around. Additionally, when food was short, the mules chewed on each other’s wool blankets and even ate them outright. Enormous suffering came as a result of the practice of clipping. By the end of the war, official doctrine had changed and clipping was limited to certain parts of the body or was eliminated completely, as it was seen to be more detrimental to health than it was helpful in preventing skin disease.

Stable sergeants were admonished to have patrols monitor the picket lines near-constantly to keep mules from eating each other’s rations, keep blankets in order, and make sure no mules had kicked each other or had gone down. Rope burns, especially on the legs, could easily become open wounds in the constant damp and dirt of the battlefield.

Poisoned gas attacks were also launched at both the mules in supply duty and at those in picket lines. If hit by a gas cloud, the mules might well die. Certainly, any food they were carrying would be ruined.

U.S. mule being fitted with a gas mask in the battlefield in the Alsace region of Germany, Aug. 31, 1918.

Several kinds of gas were used, some which injured the lungs (phosgene, chlorine) and some which burned the skin as well (mustard gas). Gas masks were developed for horses and mules, but proved impractical, since the animals could not breathe well enough with the masks on to do more than a slow walk. Of course, the masks were useless against mustard gas, the kind of gas that burned all exposed skin and tissues.

The standard practice if a gas attack was detected while the animals were in camp, was to turn all animals loose in the hopes that they could avoid the gas clouds, which dissipated quickly as they were blown about by any breeze.

With far fewer animals available than were needed, the ones that were there were worked very hard. At the worst, they worked 24, 48, or even 72 hours without being unharnessed or without breaks to eat more than a few mouthfuls. Thankfully, this was not the norm, but it was not unheard of. It was only the incredible stamina and fundamentally strong constitution of the mule that kept the animals going. Many died of exhaustion and malnourishment.

Three years after the war ended, The Quartermaster Review published a humorous piece soliciting entries for a contest to provide a medal (worth $25.00!) to an army mule as a token of distinguished service. After all, it was reasoned, medals had been awarded to a pigeon, a dog, and a horse, but mules had been left out. But it appears that there were no entries in the contest, and though the deadline was extended, there is no mention of the medal ever having been awarded. April 1, 1921 was to have been ALL MULES DAY, and it is sad to think that no one cared enough about these four-legged service members to follow up on the plan11.

Purchase and shipment of mules to ports in the U.S. and on to Europe or England by ship is covered here.

For a detailed discussion of numbers of animals, their cost, and cost of shipping, click here.

For disposal of animals after the end of the war, click here.

Sources:

- Galtrey, Sidney, Capt., The Horse and The War. Country Life, Tavistock, 1918, p. 35.

- The Tennessean, Nashville, TN, Sunday Sept 12, 1915, p. 49.

- Ibid, Galtrey, p. 43.

- The Quartermaster Review, March/April 1946

- For details on numbers of animals, see By the Numbers

- The Quartermaster Review, September-October 1921, 74, reprinted from The Christian Science Monitor, May 6, 1921, p. 3

- Ibid., Galtrey, p. 43

- Essin, Emmitt M., Shavetails and Bell Sharps, (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), p. 153

- ibid., Essin, p. 96

- Notes on Horse Management In the Field, Prepared in the Veterinary Department for General Staff, War Office, 1919 (British War Office publication)

- The Quartermaster Review, September-October 1921, p. 74.