Forgotten Comrades of Henry Johnson & Neadom Roberts

Published: 7 November 2025

By Richard Sears Walling

Special to the Doughboy Fundation website

cr monplaisir 1918 by landon

Map of the fight at CG 29 by Lt. Harold Landon.

History is written by the victors, as the old saying goes. And so, the famous story of the fight of two men of the 369th US Infantry against upwards of twenty-four Germans along the banks of the Dormoise River near Bois d’Hauzy was written by officers of the original 15th New York National Guard. The regiment was created in 1916 and from the beginning, its commanding officer, Colonel William Hayward, protégé of then Governor Whitman, worked hard at creating a legend for his men, and for himself. One early example was the 1917 Tin-Pan Ally song, “Billy Boy” about Hayward, and featuring a very imperious-looking portrait of the Colonel on the cover of the sheet music.

When two men of the 15th New York fought against a raiding party in the very early morning hours of May 14, 1918, their story became a cause celeb and national news. Three other men present that night, two of whom were replacements, were left out of the narrative.

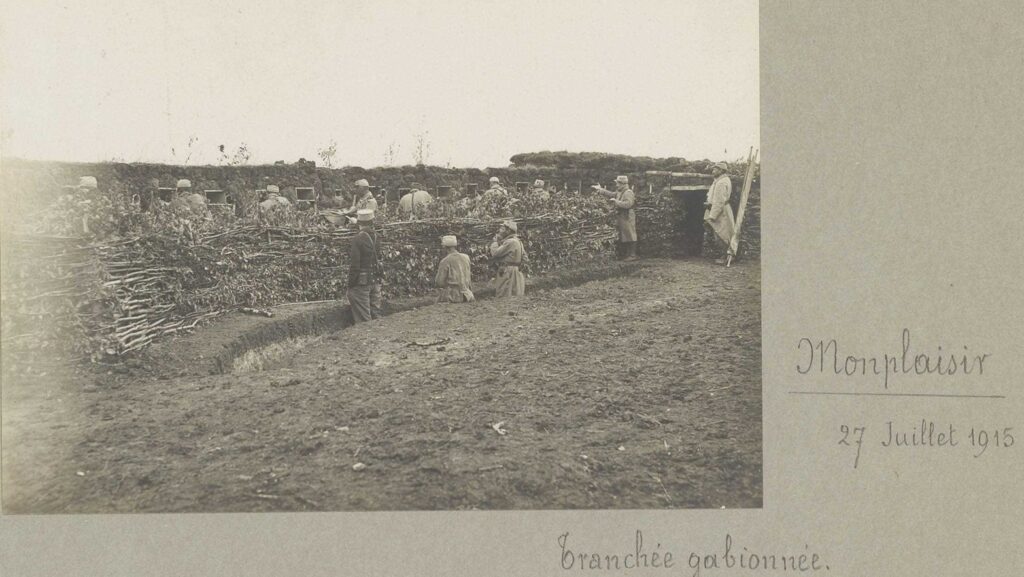

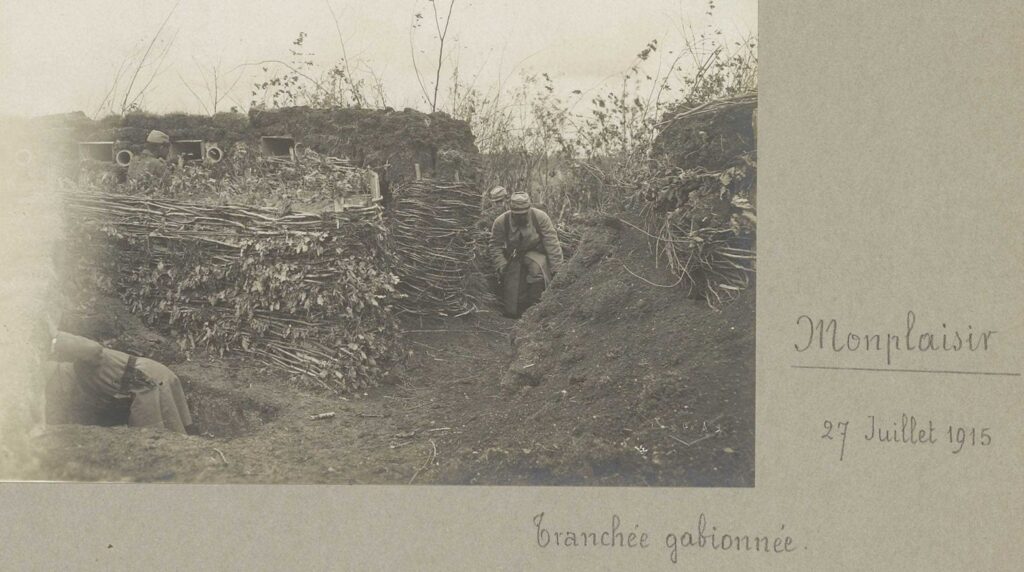

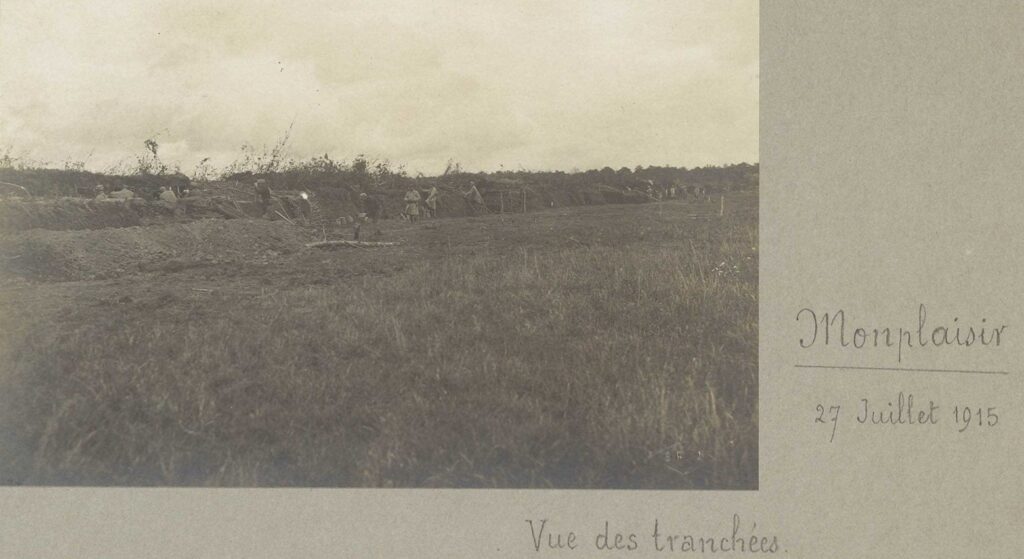

Montplaisir Ferme (farm) was a fortified position in the line of defense between Ville-sur-Tourbe and Bois d’Hauzy. Group Combat (GC) Post 29 lay a few hundred feet east of the farm on the road leading between Ville-sur-Turbe and the small community of Malmy, which borders the Bois d’Hauzy. The area witnessed very heavy combat in 1915, but by the spring of 1918, it was a quiet sector.

The 369th US Infantry, formerly the 15th New York National Guard, had been loaned to the French Army shortly after its arrival in France in January 1918. As spring approached, it entered the combat zone in mid-April 1918. It was at this exact time that several hundred replacement troops arrived from Camp Lee, Virginia, and went right into action; twenty-nine of them were assigned to C Company, First Battalion.

Two of these new Virginia replacements were led to GC 29 by Sergeant Lloyd N. Thompson of New York City. Thompson was a tall, eighteen-year-old native New Yorker who later earned an individual Croix de Guerre for a subsequent action. Thomas Eugene Ragsdale and Alfred Fields had joined C Company, First Battalion on April 13, 1918, just as the entire regiment first entered front-line combat at nearby Main de Massiges.

Ragsdale was from Kenbridge, Lunenburg County, Virginia, a small town southwest of Petersburg, and close to the Appomattox and Farmville. His grandfather was born into slavery in the early 1820s, and his dad was born in 1856. Both men were farmers, and Thomas grew up in a large family of nine children and two parents. All helped on the family farm. On October 26, 1917, at the age of twenty-four, he was inducted into the United States Army and trained at Camp Lee, near Petersburg. He stood at 5 feet, four inches.

Also at Camp Lee at the same time was Alfred Fields, from Colonial Beach, Westmoreland County. Alfred grew up near Stratford Hall, ancestral home of the Robert E. Lee family. Colonial Beach is on the Potomac River, some thirty miles from the Chesapeake Bay. In 1920, for example, Alfred was an oyster dredger. Born in 1893 according to his birth record, he was twenty-four at the time of joining the army. He was of medium height and build.

The sources for these two men being present with Johnson and Roberts on that fateful night include Ragsdale’s answers on the Virginia Veteran Survey, dated October 18, 1920 and a newspaper account from Sgt. Henry Johnson from an impromptu interview in St. Louis, Missouri in 1919 while on a speaking engagement in that city. Other articles from immediately after the fight also reference the three men as being present.

In his veteran’s survey, Ragsdale related that he arrived in France on March 26th and transferred to the C Company of the 369th by April. On May 14, 1918, he first went into combat with “Johnson and Roberts.”

Although Alfred Fields never filled out a survey form, his military record parallels that of Ragsdale. He too arrived in France with the March Camp Lee replacements and also joined C Company in April. Unfortunately for posterity, all other records for Fields conclude with the 1920 census.

The fight at Group Combat post Number 29 was investigated by Major Arthur Little, Commander of the First Battalion. He was stationed at the Command Post Montplaisir, situated at Malmy, just south of the Montplaisir Farm. The main line consisted of combat groups and trenches. This line of outposts was garrisoned at night as a first line of observation and from which to conduct raids.

A description of what a G.C. is warranted so the reader may know exactly what the combat zone looked like. Sgt. Clinton Peterson of K Company wrote in his memoir, My Year in France, the following:

Most people are, I think under the impression that the trenches are long ditches running parallel to each other, filled with men standing side by side with their rifles lying on the “parapet,” as the dirt which is heaped up in the front is called.

You find trenches running this way from one fighting post to another occasionally but, more often, you have to go back and get in another trench that leads up to the next fighting post, which may be within calling distance.

Imagine two large trees with their tops trimmed off squarely and laid down on the ground with the tips toward each other and with a space between them varying from grenade throwing distance to one half mile, and you have an idea of the great mass of network that was laid on the battlefields of Europe.

The ends terminate in what the French call “groupe de combat,” meaning combat group. The entire affair is handled at the trunk and, as the troops go in the line they are separated, and this continues until the members who go in the G.C. (Groupe de Combat) varies from twelve to twenty-five. These G.Cs. are surrounded by great masses of barbed wire and the space between the G.Cs. is also thickly strewn with it.

The company is divided into platoons or sections [average of twenty-six men], and sub-divided into half sections. It is one of these half sections that occupy a G.C.

We had several men on posts at points quite distant from one another and it was my duty to go from one to the other all night and see that reliefs were made and that everything was alright. It was nearly dark as we went into position and we locked ourselves in the G.C. by closing gates which dropped in the trenches and fastened from the inside.

All night long the enemy kept sending up rockets which made No Man’s Land as light as day, except for about two hours during which time they had a patrol out. They wanted it kept as dark as possible then so their men would not be seen. We could hear them as they would signal from time to time. This signaling is done by whistling to imitate some bird, and if a patrol separates, each part knows just what to do by the information given by pre-arranged signals.

In each of these G.Cs. there is ample ammunition to last several days should circumstances force them to lose communication with the P.C. (French abbreviation for the Post Commandant) which is company headquarters. There are all sorts of tools and equipment at these advanced positions to meet all needs, such as rubber boots for working parties when wet, pumps to pump water from the dug-outs, barbed wire to repair any that might be destroyed by shells, large metal boxes filled with emergency rations to be used when supplies are cut off in the rear.

First Battalion commander Major Little reconstructed his post-action report of the fight at CG 29. He described that this post was manned by four men and a corporal (sergeant). He incorrectly wrote that GC 29 and GC 28 were only one hundred and seventy-five feet apart from one another. Actually, these posts were about thirteen hundred feet apart, as shown on a contemporary map by Lt. Harold Landon. Similar French maps also show this configuration.

On the night of May 14, GC 28 was commanded by C Company’s Second Lieutenant Richardson Pratt, of the famous Pratt family of New York. His command consisted of half of a section, which amounted to approximately thirteen men, including a Chauchat automatic rifleman.

The First Battalion had taken over Center of Resistance Montplaisir from the Second Battalion several days earlier. On May 12 and May 13, patrols went out at night to scout and take prisoners. At the same time, German raiders were doing the same.

On the night of May 14, Corporal Henry Johnson and Private Neadom Roberts were at GC 28 and were due to be relieved at midnight. Here we pick up the story from an early account of Corporal (later Sergeant) Henry Johnson when he was interviewed prior to his speaking engagement in St. Louis in April 1919:

“It was one night in May. Two green men – they were… Freese [Fields] and Ragsdale, I believe, were at the post when I heard about it. I took two experienced men up to relieve them. After relieving them the Germans came along – and, and… Here Johnson paused. “What happened,” asked a man in the smoking compartment. Well, just this, Johnson replied: Henry Johnson jes done his duty. That’s all.’ “(St. Louis Post and Dispatch, March 28, 1919, p. 20)

In another article he stated:

“They ain’t much to be told about these here decorations except this: I am out in the Bois de Hansey [Hauzy], in the Argonne, on the night of May 5 [14-15] last. I’m on petit post, as they call it in French. Me and Needham Roberts – you heard about Needham? – is on this petit post. It’s midnight and they send out a relief. I see right away that these two relief is very raw. Me and Needham is supposed to go back, but we couldn’t see it. We stayed right there, these two reliefs being so raw. Roberts went down in the dugout to take a little sleep, and me, being awake, I hear a rustling. There’s more and more rustlings, and I whisper down to Roberts, ‘Man, man! Every German Dutchman in the world is going to rush us, Needham!”

Johnson continued his story about more noise and Roberts coming up to join him on lookout. They assemble ammunition clips and grenades. “

“This here rustling and rustling it get nearer and nearer. About 2 o’clock in the morning I tell the two raw boys out to relieve us to go to bed in the mud. They weren’t no good, being raw. And then me and Needham we picks up the hand grenades and we begin to throw them. I guess right there I began to fill the little old game bag.” (New York Herald, February 13, 1919, page 5)

The noise of wires being cut alerted a neighboring post and flares went up. The German raiders attacked, throwing grenades. Roberts was wounded and nearly captured. Johnson fired his rifle till it jammed and he attacked his foes with his bolo knife, gutting one and stabbing another through the skull. At this point, the Germans retreated, with both men lobbing grenades after them. Johnson first stated the fight lasted three minutes, but eventually it became an hour-long combat among the shell holes outside of the post. Officials determined the raiding party amounted to between ten to twenty-four Germans.

But what of the three men who were there with Johnson and Roberts? Thomas M Johnson the New York Evening Sun wrote:

The other three Americans at the post were just emerging from their dugout when the fight commenced and were knocked down by the force of exploding grenades. They got to their feet barely in time to see the last of the Boches disappearing. They gave chase but could not catch up with the fleet footed foe. (The New York Age, May 25, 1918, p. 2)

Johnson also stated in a very embellished interview:

“I was still banging them when my crowd came up and saved me and beat the Germans off. That fight lasted about an hour. That’s about all. There wasn’t so much to it. “(History of the American Negro in the Great World War, W. Allison Sweeney, 1919, Chapter XV.)

Neadom Roberts stated “the firing aroused a machine gun company in the Allied trenches and also the supporting artillery.” (Port Chester The Daily Item, March 21, 1919, p.1)

The story of The Fight of Henry Johnson was developed into a tremendous publicity affair. As fate would have it, three American journalists arrived at headquarters of the 369th on May 15. Major Little nonchalantly told them of a “little” fight and then escorted the reporters to GC 29, and even further out into No Man’s Land where more evidence of the raid was located. The reporters realized a good story and Major Little was happy to tell them about the fight of the New Yorkers.

Major Little wrote:

“The 15th New York Infantry had passed out of the category of a merely unique organization of the American Army…Our colored volunteers from Harlem had become, in a day, one of the most famous fighting regiments of the World War.”

Colonel William Hayward credited the event with having saved the regiment:

In the belief of their white commander, a former Public Service Commissioner of New York city, the two negroes by their valor and intelligence frustrated a well-developed plan to assail one of our most important positions of resistance. (NY Age, May 20, 1918, p. 2)

If we take a step back and look at all the details, and how those details changed with each telling of the tale, we should consider the confusion of close-quarters combat. With Johnson focused on his own actions and occasionally looking at Roberts during his hand-to-hand combat with the raiders, could he have missed these three men shouldering their rifles and firing into the darkness towards the enemy? Is it possible that in promoting the glory of the 15th New York National Guard, as its commanding officer, Colonel William Hayward constantly did, that the story of these men did not fit the chosen narrative?

These are hypothetical questions, but ones that should be considered. The GC 29 was large enough to accommodate several men and included a dugout. Would soldiers be sleeping in the mud while all Hell was breaking loose above their heads? We have the official version, and we have the names of three men who were left out of the record.

Only through ongoing research will such oversights be corrected. Thomas Ragsdale, a farmhand from Lunenburg, Virginia reported his presence on that fateful night. Alfred Fields and Lloyd N. Thompson were also there. Did they remain stunned into inaction or would they have acted like soldiers and defended the post. If they were stunned by grenade explosions, then why were Johnson and Roberts not affected to the same degree?

Was the tendency to promote the regiment so influential that these men became superfluous to the story? Colonel Hayward and some of his subordinates were immensely proud of their regiment and took strong measures to garner attention to its record.

I suspect the after-action report about the early morning hours of May 15, 1918 along the foggy banks of the Dormoise River may have been an early step in that process.

Research notes:

- Other examples of promoting the regiment include Col. Hayward chosen to lead the Red Cross Parade in NY City on October 4,1917; the deliberate formation of the famed regimental band; Hayward’s personal relationship with General Pershing and the former’s push to get the regiment to France as early as possible prior to the organization of the 93rd

- Although not named specifically along with Fields and Ragsdale, Johnson mentioned Thompson as the NCO who brought the two men to GC 29.

- Company C muster roll for April to June 1918 shows that Henry Johnson was promoted to corporal on May 2, 1918.

- All men of the regiment, both original 15th NY NG and replacement troops have been identified and military service records analyzed.

- Ragsdale was promoted to PFC in November 1918.

- Maps of the Ville-sur-Tourbe to Ainse River by both French and American sources depict military positions and terrain features.

- I visited these sites in both November 2022 and April 2024 with the guidance of military historians. The remains of war still litter the fields and forests, a mute reminder to the conflict of more than a century ago.

The author is a historian focusing on Native American and African American history with a special focus on the 369th US Infantry. The son of World War Two officers, he is a graduate of Rutgers University. He may be reached at [email protected].

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.