Emigration and World War 1 – Swedish born soldiers in The American Expeditionary Forces

Published: 16 August 2024

By Joacim Hallberg

Special to the Doughboy Foundation website

AEF

Of the 2 million men in the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I, an unknown number were Swedish immigrants. At least 258 individuals who died in service are buried in America cemeteries in France and Belgium.

Swedish born soldiers in the Great War?

It is interesting to ask why and how Swedish born individuals ended up participating in the Great War during 1914 to 1918. Sweden, as a country, was neutral at that time, even if it was affected by the war.

Most of the Swedish born individuals in my research participated after they emigrated and became citizens in their new countries. Many of the men who left Sweden did so either as infants, small children or before they were of an age to be called upon for conscription in the Swedish armed forces. A large amount was then called upon when it was time to draft men to their respective armies, under the different Military Service Acts. A large part of them volunteered before conscription.

Swedish emigration

Between the years 1821 and 1930 around 1,200,000 Swedes left Sweden, of those about 1 million to North America, which was around 20% of the total Swedish population at that time. The reasons for emigration were often economy, poverty and hunger, not enough work for the population, but also the dream about a better life and to get more money through other opportunities, especially in North America and Canada. The development of the steam engine made it possible to travel more easily to other continents.

When it comes to those Swedes who immigrated to Canada, 1680 of them signed up for Canada in World War 1, 1233 as volunteers and 447 as conscripts. 122 of those made the supreme sacrifice. I have been able to find 113 of those 122 mentioned by the author Elinor Barr. I have found examples of Canadian individuals who stated they were born in Sweden but were born in Finland or other countries. That is an interesting subject to investigate further. Canadian conscription was introduced due to heavy losses, on September 20, 1917. However, the French-Canadian population did not concur with these demands. It applied to all men between the ages of 20 and 45. Conscription became more popular among the English Canadian citizens, and among the women who were closely related to those who served as they were given the right to vote at the same time.

It is hard to find an exact number of Swedish immigrants who participated in the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), due to quite different information found in archives and in other sources, however so far, I have confirmed 285 (August 9, 2024) Swedish born soldiers who fought and fell for AEF and are buried or commemorated in Belgium and France.

In my research I have mainly covered those soldiers who participated and fell on the Western Front in the War, but I have now started to explore those Swedish born soldiers who participated and survived, went back home to North America, and either stayed there for the rest of their lives, or went back to Sweden again.

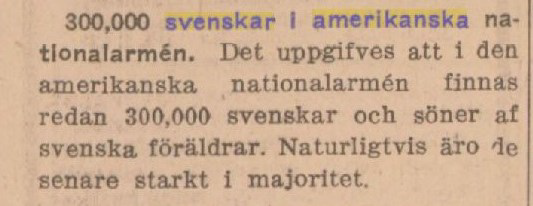

Below, one snippet from an article which describes the number of Swedish soldiers registered in the American Army.

“300,000 Swedes in the American National Army. In the American National Army there are already 300,000 Swedes and sons of Swedish parents. Naturally, the latter are in a strong majority”. (This information is from a Swedish-American newspaper from 1918, and it hasn’t been confirmed from any other source.)

Swedes to fight for Germany?

This is one of the most frequent questions I get when I do my talks to various kinds of audiences, and I always want to answer it with the most correct answer possible.

It may be hard to find the most correct answer, as I am looking into a combination of different reasons and aspects, but maybe I have found some answers when looking into the great sources of information, in the small books which honors the soldiers from each county in the US, who participated in the great war. The people in the county who wrote these texts knew their inhabitants well, and the information given in those different books is probably as close as we can get when I ask myself why and on which side these Swedish soldiers choose to participate in the Great War.

Currently I am trying to find as many books as I can that honor the local soldiers who participated in the Great War, and I have already found and read some of them, from different states. I am now looking into the states that are known for having a larger population connected to Sweden and Scandinavia.

In this case I have studied the Book “Chisago County, Minnesota, in the World War”. The reason for that will be described below.

In this case I have studied the Book “Chisago County, Minnesota, in the World War”. The reason for that will be described below.

Back in 1920 Chisago County in Minnesota, was the most typical Swedish-American County in America. They assessed at that time that 95% per cent of the inhabitants were of Swedish birth, or descendants of Swedish born parents. It had the largest congregation in proportion to the total population of any county in the United States at that time.

The Swedish settlers already presented themselves in the Civil War. Minnesota was the first state in the Union to offer a regiment to President Lincoln at that time. Many sturdy Swedish boys from Chisago County, boys who could hardly talk the language of their new land, but their souls fired with love to their new-found land, “taught by their noble pastors, that loyalty to their country was the first duty of a Christian Citizen “, as it is described in the book.

One pillar of their determination to participate can maybe be brought from their Christian heritage. One piece from the book says:

“The early pioneers of this county were of the sturdy, disciplined, religious type, thorough and faithful Christians. Closely following the first pioneers came the ministers of the Gospel sharing cheerfully the privations of the settlers, utterly unselfish, bent only on keeping the religious faith of their people untarnished.

Think of the sacrifice these men had to offer. All of them extremely poor, some with a young wife, and many children, others with aged parents to support, most of them heavily in debt, small patches of clearing in the heavy forest, wild animals prowling in the timber, Indians not entirely friendly, living nearby.

Yet these splendid young men volunteered in great numbers, many of them never to return. The attitude of these Swedish settlers toward their newly adopted country is a shining, glorious mark in Chisago county’s history. “

Other pillars in their determination could have been as described below:

“Why were these men so solidly loyal? Why was there not one single copperhead among the Swedish boys? Many, no doubt, were actuated by a spirit of adventure, the joy of battle which had made the name of their Viking ancestors’ immortal in history. It is also easy to imagine that human slavery, the buying and selling of human beings, though their skin was black, fired the souls of these liberty loving Swedes with indignation, and they freely offered their services and lives to destroy this dreadful institution. But in addition to the splendid attitude of their religious leaders previously noted, one tremendously important matter must here be noted”.

One reason could also have been the influence of the only newspaper the Swedish settlers read at that time, the newspaper “Hemlandet”, which was active to the end of 19th century, and of course media, as today had a great influence of what to think and what to do, and maybe a feeling of security to stand among a common taken stand in their new country?

The statement to support its new country was probably rooted already during the end of 19th century and brought further on into those who emigrated later, with Swedish born children and children born in US by Swedish parents, who later were in the age of to be drafted to the first world war.

Read more from a text from the book below:

“Prior to and during the Civil War, our people read only one newspaper, the glorious old “Hemlandet.” There were no other papers in circulation here among the Swedes. Hemlandet was the semi-official organ of the Swedish Lutheran Church, and its principal contributors were the Lutheran ministers. Thank God for these men! They wrote strong editorials on the duty of a Christian to support the flag of their country they espoused, the cause of human liberty, they upheld the cause of the Union in the plainest and sturdiest of languages. Oh, that full credit might be given to these noble men for the wonderful influence they wielded for loyalty, justice, and devotion, to their God, their country, and their flag “

In the book you will find a considerable number of soldiers born in the US, by Swedish born parents, and quite many of them paid the ultimate price, by dying of disease or in battle. Most of the soldiers from the county of Chisago died of disease, some of them on the battlefield in France, where some of them also have their final resting place.

Lindström, maybe more than any other Chisago County community, supported the country in World War I with volunteers. The Lindström Naval Militia went to war on April 7, 1917. From Lindströmsjö Lindstrom on the Lake 1994. (Via Charles Gramling, Chisago County County Minnesota Facebook Group.)

Further on we can read about an interesting perspective described in the book about why Sweden and Swedes didn’t participate on the German side which would have been more natural, or?

I have earlier mentioned Sweden’s history with Russia as a natural statement to fight together with the words” Our enemy’s enemy is our friend”. That would have been a clearer way of choosing a side in the war. Our political statement from the period of the first world war were also more leaning towards the German side, and some of the officers from the Swedish army went to war on the German side, but not as many as we thought, as my research also shows when it comes to the individuals who fell for the different sides.

The Chisago County book also mentions four perspectives that makes Sweden more connected to Germany at that time, but in the end also explains a reason why it did not become like that when it comes to the Swedes who emigrated to North America at that time. A short summary of the text from the book below:

-

For hundreds of years or more (at least) Swedish people had an intense dislike, even hatred for Russia on account of Finland.

-

England had since the Revolution been our historic enemy. Our school histories, relating the story of the Revolutionary War, influenced the school children against England. The war of 1812 was likewise chronicled in a manner to arouse our indignation.

-

The Swedish people, in many respects, are much like the German people. Both are of the Teutonic race. The language is largely identical, or at least very similar. The German people in the United States were simple, honest, thrifty, kindly persons, splendid citizens, law abiding, peace loving, easy to get along with.

-

Germany was the birthplace of Martin Luther, the great founder of the church bearing his name, and to this church belonged most of the Swedish people. It was almost impossible to believe that Germany, the great patron saint of the church, the gentle, wonderful leader of the great Reformation, could have so utterly changed, and become the great barbarian nation that characterized the starting of this terrible war, and its conduct thereafter. Aided by clever and perniciously active German propaganda, our people were inclined at the beginning to call these stories “English lies.” The rape of Belgium, the “scrap of paper” incident, the enslavement and deportation of Belgian men and women, the horrid atrocities, carried out in accord with their doctrine of “Schrecklichkeit,” the sacking of Louvain, and other acts which would make an Apache Indian blush with shame, were not believed true.

So – what made us not follow these above-described perspectives?

The book describes it with those, quite simple words below, and was probably not the whole truth, more a reason in combination with all the others described above the four reasons above:

“But there were hundreds of our people, yes nearly a majority, who at once saw through Germany’s plan, and unhesitatingly took the side of the Allies. When our good president made his appeal to our people to be neutral, and avoid controversy on this subject, those friendly to the Allies, followed his admonition more than the other side, we think. “

But was it easy all the way?

I have earlier described in my research that many of the Swedish born soldiers left Sweden before they became 21, when they were supposed to be drafted for the Swedish Army through our current service act at that time.

The Chisago County book also describes some antiwar demonstrations, with protests not to send our boys to France. The Audience, many of them, probably Swedes, were driven into a frenzy of wild protests against the war. Many asked themselves if the Swedes suddenly had lost the sense of giving such aid?

Although, it was without delay determined that there should not be a repetition of such a meeting. The Minnesota Conference later, of the Swedish Lutheran Church met in annual meeting about a month after declaration of war. Its first act was to pass a resolution of loyalty with much enthusiasm. Even if it was some protest, it all went well in the end.

As the largest group of those Swedish born soldiers, present in my research, who fell and are buried in France or Belgium, were Americans, the reasons explained above are connected to them. It can also include the soldiers who fought for Canada as well, even if I think they probably were affected by English and French values, depending on where they lived in Canada.

I will not draw any final conclusions, but some of the basic religious reasons mentioned above can be applicable to those soldiers who fought for other countries in the commonwealth, such as Australia and New Zealand.

The poverty and the social situations affected the Swedes and ended up in reasons to emigrate. I believe the economic situation in their new countries affected the individual in a way to see the role as a soldier in an army as a job, without so much influence from any other reasons.

I am a bit closer, when it comes to presenting some reasons why the Swedish soldiers fought on either side in the Great War. I think a lot was connected to the inner values but later affected by the values of the community, in their new home countries. I can see that we have the same situation today, even if the economic and social situations do not affect us as much as back then, in our choice to take part in any modern conflict.

They fought together.

In my research I sometimes try to merge different facts that I find in digital sources, to discover that many of the Swedish born soldiers went to war in the same units and experienced a lot of the situations together. So far, I have not located any letters or other documents that confirms they have been side to side, but highly likely they knew about each other even if they fought in different companies.

I have made some different compilations, like this story which tells the situation of some of the Swedish born soldiers who fought for the 28th Division, AEF.

The 28th Division in the AEF, sometimes known as the “Iron Division” was formed from the National Guard in Pennsylvania. They were trained at Camp Hancock, Augusta, Georgia, and first arrived in France in May 1918. The first unit arrived in France May 14th, 1918, and the last element arrived June 11th, 1918.

For training purposes, the unit was attached to the 34th British Division south of Saint-Omer, France, and remained attached until June 9th, 1918. On June 13th the unit was attached to French troops in the vicinity of Paris. The Artillery Brigade from the 28th Division went to Camp Meucon for the same purposes.

Following Swedes were fighting in the 28th Division, fell and buried in France.

- Carl E Blomkvist (Carl Edvin Blomqvist) 55th Brigade, 108th MG

- Fritz E Benson (Fritz Edmund Constantin Olsson) 55th Brigade, 109th

- Carl M Bostrom (Karl Magnus Boström) 55th Brigade, 110th

- Per E S Carlson (Per Erik Severin Petersson) 55th Brigade, 110th

- Theodore Edling (Vilhelm Teodor Edling) 56th Brigade, 112th

- Anton H Nelson (Anton Hjalmar Nilsson) 56th Brigade, 112th

One of the main purposes in my research is to describe the story of everyone, from when they were born, their story in their new home country, their military service, and where they found their final rest. The information will then be presented in my upcoming book, the second edition in my book series about the Swedes who fell at the Western Front, where I will tell the stories about the Swedish born soldiers who are buried and commemorated in Meuse Argonne American Cemetery (153 soldiers)

Buried in Sweden

In my research I have discovered that some of the Swedish born soldiers, who fell for AEF in the war, were disinterred and reburied back home in North America. Some of them were transported directly to Sweden from Belgium or France. So far, I have located 17 soldiers within these criteria. 15 of them were born in Sweden and two of them were born in the USA by Swedish parents.

The relatives to the deceased soldiers were asked during the reburial process if they wanted their relatives to remain in France or Belgium, or transported back to the USA, or in these cases, to Sweden.

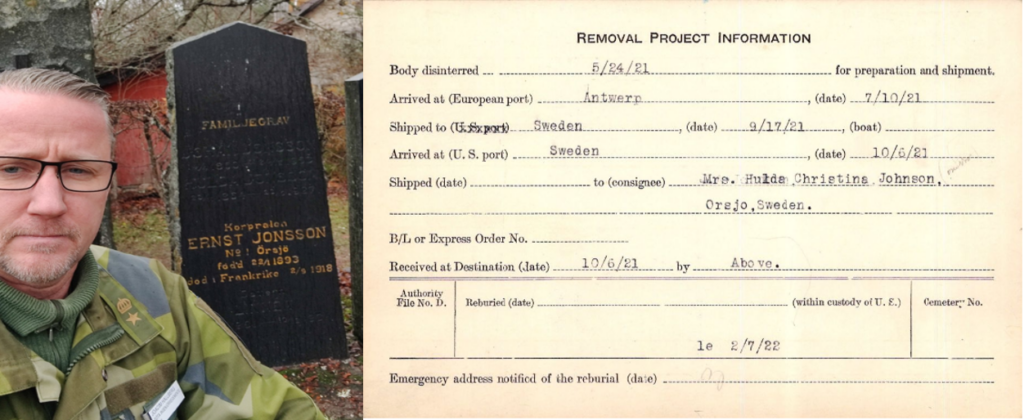

There is no Swedish burial registry to search for these soldiers, to try to locate their burial site in Sweden, but I have managed to locate some of the soldiers and their final resting places. Below you will find a photo of me visiting one of the soldiers, Ernest Johnson (Ernst Hildemar Valentin Jonsson), who fought for 128th Infantry Regiment, 32nd Division, AEF. He died of wounds on September 2nd, 1918.

Author Joacim Hallberg pictured by the headstone of soldiers, Ernest Johnson (Ernst Hildemar Valentin Jonsson), who died of wounds on September 2nd, 1918 while serving in the AEF.

In some cases, I have contact with descendants to the soldiers, in Sweden and in the USA. If I have the opportunity, I try to visit the burial sites of the soldiers’ parents, who still have their headstones present in Swedish cemeteries. This is a nice way of connecting the history. Below photos from when I visited the parents of the Swedish born soldier Axel T Rydell. They are buried at Moheda Cemetery near Växjö, Småland, Sweden. Below also photos of the parents[1] and their son, Axel Tolli Rydell, who fought for 362nd Infantry regiment, 91st Division, AEF. Axel was one of 285 Swedish born soldiers who fought for AEF in WW1, fell, and are buried along the Western Front.

Author Joacim Hallberg at left, next to the headstone of Axel Tolli Rydell (center). Axel served with the 362nd Infantry regiment, 91st Division, AEF. His parents (right) are buried near Växjö, Småland, Sweden. (Parents’ photo courtesy Philippe Colinet, caretaker in Flanders Fields American Cemetery, Belgium.

Traces in Sweden

On some occasions, during my talks about my research, people in the audience contact me after the talk and tell me about relatives who fought in the First World War, for AEF, and then went back to Sweden. Quite often they decide to look more into this, and it is common that they find artifacts from the soldiers, from their time in service.

Per Erick Person (Per Erik Persson) was born on December 26th, 1891. He left Sweden for North America in 1911, participated in the war, and came back to the USA after the war, in 1919. He later went back to Sweden again in 1921.

Per Erick belonged to the 54th Pioneer Infantry and fought with his unit in the Meuse Argonne Offensive.

A small story that still lives on within the family is about how Per Erick and his friend joined the American Army. One day they were confronted by an angry crowd of people, who knew they were immigrants. The crowd seemed to be forcing people to join the army, and Per Erick and his friend weren’t sure how to act as they were immigrants, but the crowd shouted; -“Hang them, Hang them!” so in the situation the felt forced to visit a recruiting office to sign. They would have been drafted anyway, and I am sure they already had decided, if it would be the case, to support their new home country.

Below are some photos[1] of objects that some of them have found when looking through the family home, connected to Per Erick Person.

(Clockwise from top left) Swedish-born Per Erik Persson, and a variety of World War I artifacts from his time in service with The American Expeditionary Forces. (Photos courtesy Sven Söderberg.)

“I was there!”

One interesting source of information is the stories from the soldiers themselves. It is interesting to read books written by Swedish born soldiers, and so far, I have found two stories written by those who participated. In the books they also describe their lives in North America, which gives me a clear picture about how it was to be an immigrant. It was not always easy.

Einar Eklof (Einar Eklöf) was born January 1st, 1893, in Sandby, Kalmar County, on the small Island of Öland on the Swedish east coast. Einar left Sweden for North America in 1912.

Einar describes his emigration, the life in North America, the time in war, when he was wounded a couple of times, both from gas and from machine gun fire, how he fought back against the German soldiers, and finally how he made it back to the US. He never found peace over there and went home again around 1925. He died at the same farm he was born on and left when he emigrated.

Einar Eklöf is pictured at left in his U.S. Armey uniform while he served with the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I, at right on the cover of his book MittLif (“My Life) published after he returned to Sweden from America later in life.

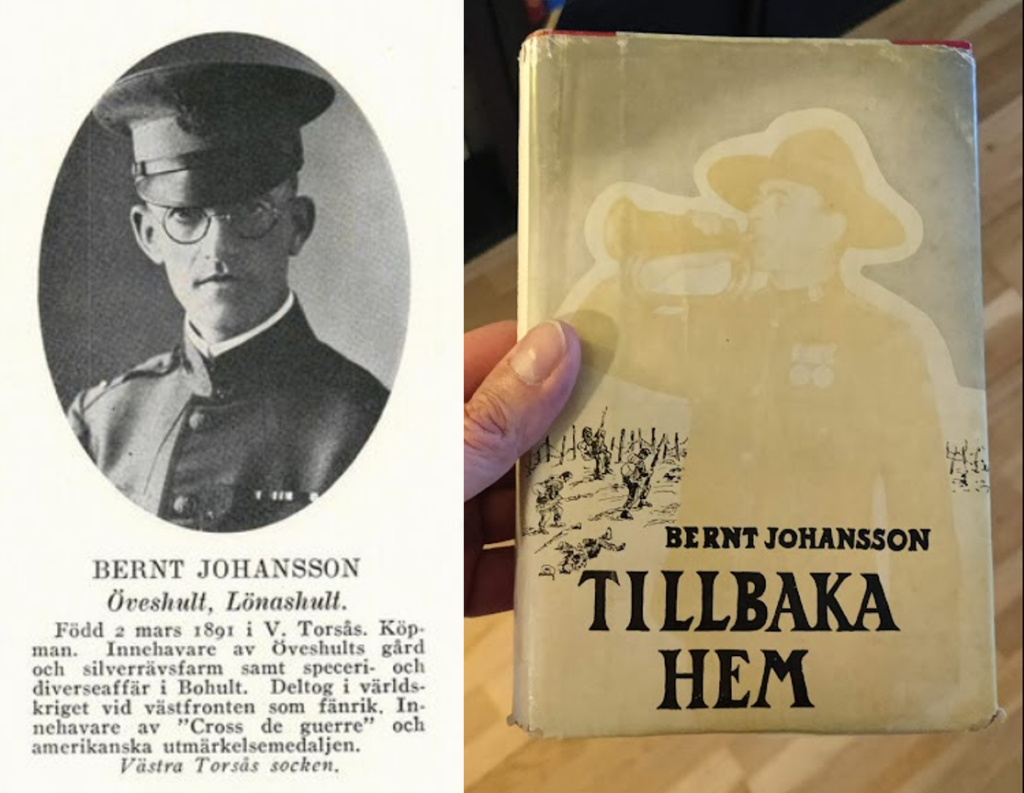

The other story is about the soldier Bernt Johansson, who arrived on the battlefield on November 9th, 1918, but managed to find himself directly in the actions during the last days before the armistice.

Bernt Arvid Johansson was born in Västra Torsås parish, Kronoberg county, Sweden, March 2nd, 1891. He left Sweden for North America in 1911, to start his new life in New York.

After his short but intense service abroad, he went home to Sweden. Bernt went down again to the battlefields in the 1950s, to visit some of his friends, who were buried in the American cemeteries in France.

Swedish-born Bernt Johansson, and his book Tillbaka Hem (“Back Home”) about his World War I experiences.

If I compare the stories from those two Swedish born soldiers, I find the story from Bernt more difficult to follow and to compare to American war diaries, which can be Bern’ts ability to remember or in some cases he wrote things that were not fully true.

Although, I have been able to trace their military service and their trips over to Europe and back again. They were lucky to survive, and their stories are, in my opinion, important contributions to Swedish military history.

Many of the Swedish born soldiers, who fought in the war and survived, went back to their homes in the US, and stayed there for the rest of their lives. Some of them had interesting stories to bring back home.

Like the story of Frank G S Erickson (Frans Gustaf Severin Eriksson Ersson). He was the runner of the 1/LT William J Cullen, 308th Inf Regiment, 77th Division, AEF, and received the silver star for his effort during October 2-8, 1918, in the fighting with the “Lost battalion”.

Frans Gustaf Severin Eriksson was born in Torpshammar parish, Sundsvall, Sweden, December 12, 1892. Frans and his family left Sweden for North America in 1903. I have established contact with the relative of Frank, the Grand-grand son, Mark Erickson, and have received interesting information about his adventure in the AEF, and his contact with the home front in the US, through letters from the frontline.

On my next planned tour as a guide, I will yet again visit the terrain of the “Lost Battalion” and then tell my Swedish guests about the challenging situations Frank went through and were lucky to survive from.

Four other Swedish born soldiers died during the fierce fighting’s of the “Lost Battalion” on those days in October 1918. There were also some US born Swedish soldiers who participated during the fighting within the situation for the “Lost Battalion”. One of them was Hjalmer John Oselius fron Dunnell, Martin County, Minnesota. He was killed in action after having been involved in the relief of the soldiers in “The Lost Battalion”.

Below you will find some photos of Frank G S Erickson.

(left) Frank Erickson in his WWI uniform. (right) Frank’s brother, Ernest J A Erickson (Ernst Julius Alfred) also born in Sweden, 1889, was killed in action October 10th, 1918, in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive when fighting for 361st Infantry Regiment, 91st Division. He was initially buried at Meuse-Argonne Cemetery but is now buried at home in North Dakota.

(Left) Ernest J A Erickson, Frank’s first Brother, killed in action October 10th, 1918, in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. (Right) Frank’s second Brother, Anders Sebran Filimon Erickson (left). pictured with Frank. Anders participated in the war as a pilot for 101st Aero Squadron, Air Service, for the AEF. He survived the war, and he also went back to the US.

They are not forgotten.

I have dedicated my life to visit all the individuals in my research, visiting their last resting places along the Western Front. So far, I have visited most of them, of those 483 Swedish born soldiers that I have found so far within my criteria’s. I have only 19 of them left to visit, and 16 of them are buried in Suresnes American Cemetery in Paris, France.

In September the 2024 edition of my home village book of Taberg, in Jönköping, Sweden, will be released, and in this book, I have the honor to commemorate twelve of those Swedish born soldiers who emigrated from my own parish of Månsarp. Some of them participated in the Great War.

Most of them fought for AEF, and survived, but one soldier who fought on the German side, fell in the war, and is now buried in Germany.

One of the soldiers from my parish, Ernest M R Christopherson (Ernst Magnus Robert Kristoffersson) belonged to the 307th Light Field Artillery and fought in the Argonne region during October 1918. Ernst survived the fighting and in the discharge documents on May 22, 1919, it is mentioned that he has 0 percent disability, but family told me that he struggled with his hearing the rest of his life, which is not strange after had belonged to an Artillery unit, 307th Field Artillery which belonged to 153rd Field Artillery Brigade, which supported 78th Infantry Division.

Ernst Magnus Robert Kristoffersson was born in Taberg, Småland, Sweden, June 7, 1894, and he left Sweden for North America in 1910

Below is a photo of him in his American Uniform. His sister was the only one of the nine siblings to stay in Sweden. She was also the youngest, almost 25 years younger than the oldest sibling. I was able to interview the daughter of Ernest’s sister, which was amazing. They had a lot of photos, and I told them to take care of them, to save them for the future.

The research continues.

During the autumn of 2024 I have more talks to give, and I am also planning some trips down to the battlefields to prepare the upcoming tour as a guide in April 2025.

The research will also widen, to include the stories of the Swedish born soldiers who emigrated to different countries, participated in the Great War, and survived. That work will never be fully finished, but I am sure that those stories will contribute to establish a more detailed picture of the soldiers, who, in heavy times in their home country, found other lives and opportunities.

They will never be forgotten.

Joacim Hallberg is an Army Major in the Swedish Armed Forces. He has served in several missions abroad in Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Mali. He developed a huge passion for The Great War, and has visited many battlefields, especially in Belgium and in France. In West Flanders, he discovered Swedish names on the Menin Gate Memorial, and that was the starting point of his research for the Swedes in the Great War website that he now curates on his own time. As of August, 2024, he is researching 483 Swedish-born soldiers who served in the armed forces of other nations in WWI.

Joacim Hallberg is an Army Major in the Swedish Armed Forces. He has served in several missions abroad in Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Mali. He developed a huge passion for The Great War, and has visited many battlefields, especially in Belgium and in France. In West Flanders, he discovered Swedish names on the Menin Gate Memorial, and that was the starting point of his research for the Swedes in the Great War website that he now curates on his own time. As of August, 2024, he is researching 483 Swedish-born soldiers who served in the armed forces of other nations in WWI.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.