Doughboy MIA for October 2025: Second Lieutenant Eric Halbert Cummings

Published: 17 October 2025

By Daniel Williamson

Lieutenant Colonel, Retired U.S.A.

Director of Research and Field Investigation – Air

Doughboy M.I.A.

Reveille Photo framed

Our Doughboy Missing in Action (MIA) for October is Second Lieutenant Eric Halbert Cummings, Company C, 26th Infantry Regiment. Born the sixth child of nine children on 25 November 1890 in Dallas, Missouri to Anthony Benaugh Cummings and Eliza Elvira Garten, who were famers and grateful to have a big family. The couple’s brood of children consisted of five daughters and four sons, including Eric. The family moved to Grainfield, Kansas sometime between the years 1900 and 1910 for better farming opportunities.

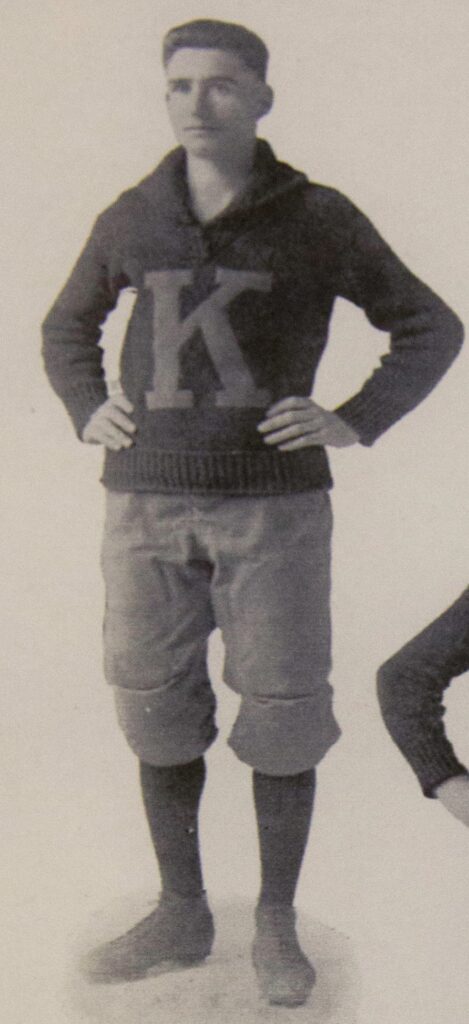

Not much is known about his formative school years except he achieved the highest score in his home district during his “diploma examination.” His score was 89.9% qualifying Eric Cummings for a year’s free college tuition in the state of Kansas. Graduating as the Valedictorian he gave a speech on education at his graduation commencement ceremony on 19 June 1909 and then using his free scholarship to attend Washburn College in 1910. His education was interrupted, working as a ranch hand before attending the Fort Hayes Normal School, now Fort Hayes State University, from 1913 to 1917. There he was popular and showed himself to be a leader, becoming the captain of both the school’s football team and the Rifle Club and became a prominent member of the school’s inter-collegiate debating team, winning the W.J. Madden Debate Prize in 1916. He was also involved in the college’s drama clubs and cast in both musicals and comedies. He graduated on 24 May 1917 with a Bachelor of Science degree in Education; however, he was not present for the graduation ceremony as he had just enlisted in the Army after giving a patriotic speech to thousands of people at a Loyalty Mass Meeting in Fort Hayes.

Two weeks after Congress declared war on Germany Eric Cummings enlisted in the U.S. Army as a private on 20 April 1917 at the recruiting office in Ellis, Kansas. He was immediately sent to Fort Logan, Colorado, a recruit induction center for new Soldiers entering military service. While there he was assigned to B Company, 23rd Infantry Regiment at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas. During his initial training he was hospitalized in May 1917 for pneumonia and had surgery to remove tumors in stomach. After recovery, he rejoined his regiment to finish his training at Camp Syracuse, NY in July 1917 where he was promoted to Private First Class on 1 July 1917. After completing this training, the Regiment boarded the USS Huron in Hoboken, New Jersey on 7 September 1917 and departed for France. The USS Huron was formerly the German owned SS Friedrich der Grosse, which was seized by the U.S. Government after the declaration of war against Germany earlier in the year and converted to a U.S. troop transport.

Upon arriving in France Eric Cummings was promoted to Corporal on 22 September 1917 and the 23rd Regiment was stationed near St. Thiebault and Goncourt, France until 17 March 1918. Here the entire regiment underwent theater combat training to prepare Soldiers to fight veteran German troops. The Regiment moved on to Ranziers and then to Lacroix. On 5 April 1918 Corporal Cummings was accepted and transferred to the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) Officer Candidate School and was commissioned a Second Lieutenant on 9 July 1918. He was likely reassigned to Company C, 26th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Division to replace heavy losses the Division had taken in the months of May and June 1918. There he would have been assigned as a Platoon Leader and trained with other replacements for the Regiment’s next battles. Most likely he would have taken part in the Aisne-Marne Offensive (18 July to 6 August 1918), the St. Mihiel Offensive (12 to 16 September 1918), and was present during the Meuse-Agronne Offensive (26 September to 11 November 1918). It would be during this last campaign that 2LT Cummings would be killed.

On the night of 3 October 1918, the 1st Division, of 1st Corps, was given the mission to drive northward and clear the enemy east of the Aire River and out-flank German forces in the Argonne Forest. The intent was to create the situation to allow the entire American Army to move forward more rapidly. The immediate plan was to attack early on the morning of 4 October to capture the town of Exermont as well as clear enemy forces off both Hill 240 north of the town and Hill 212 beyond the town. To do this, the Division’s far right unit, the 26th Infantry Regiment, would have to capture the ravine and the heights to the eastern side of Exermont. The Regiment’s attack was organized with the First Battalion in the lead for the assault with four infantry companies and the Regiment’s machinegun company, the Second Battalion would support with four companies, and Third Battalion would follow as a reserve with four companies. Company C, Lieutenant Cummings’s unit, was in the First Battalion and therefore part of the assaulting element.

A key element of this assault was to maintain contact with adjacent units as the Regiment moved forward so their flanks would be secure. Since the 26th Regiment was on the 1st Division’s far right, the Regiment had to coordinate and liaison with the 32nd Division so both divisions remained aligned moving forward. Because of his intelligence, experience, and excellent communication skills, the 27-year-old Lieutenant Cummings was given two infantry squads to command and tasked to conduct liaison patrols so the Regiment could maintain contact with the 32nd Division’s left most units.

At precisely at 0525 in the morning darkness and slowly dissipating fog, the Allied artillery bombardment began to prepare the enemy positions for the attack. The Germans had occupied their positions since 1914 and prepared the area with camouflaged and dug in positions. These fighting positions and entrenchments had overlapping machinegun fields of fire and predetermined “registered” artillery fire points for immediate responses to attack. The Germans immediately began counter battery artillery fire and fired red star shells to notify all the German Soldiers that they were about to be attacked. The 1st Battalion assault started at 0530 following 200 yards behind the Allied artillery barrage that slowly began creeping towards the German positions. The German troops began a heavy machinegun fire from the north, northeast, and east into the advancing Americans of the 1st Battalion.

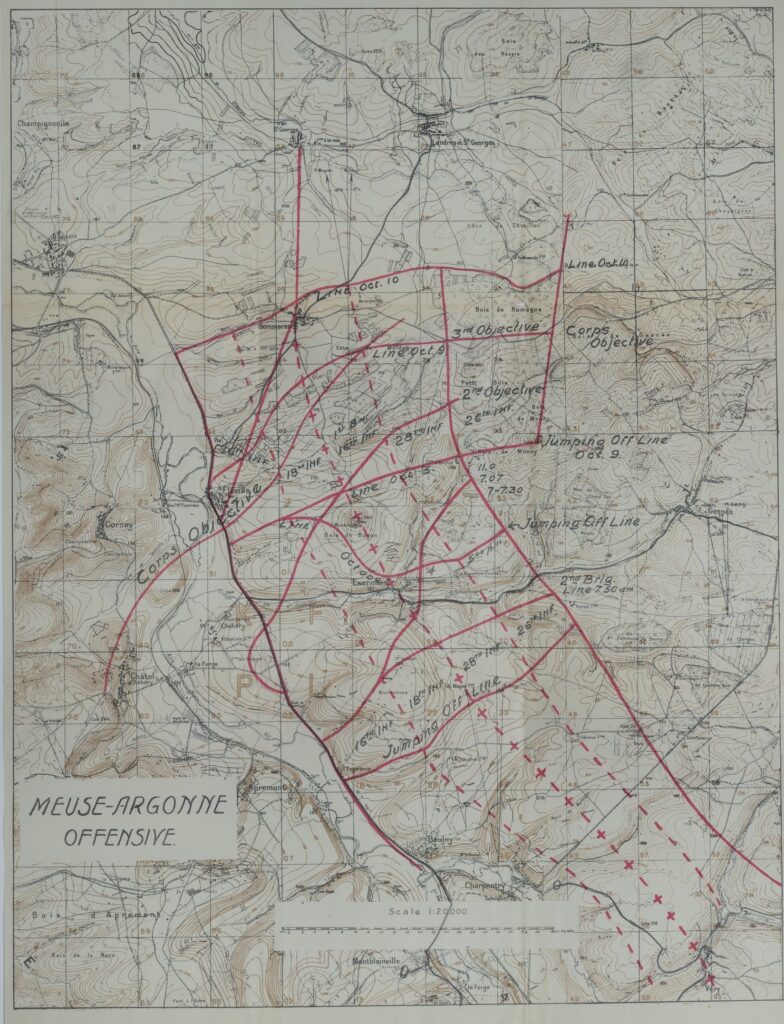

A portion of a French map that is annotated to show the lines and objectives of the 1st Division from October 4 to October 10, 1918. The 16th, 18th, 26th, and 28th Infantry are represented on this map. Print on the back reads: “Map No. IX: Meuse-Argonne Offensive.” (The Harry S. Truman Library and Museum)

It was just after jumping off at 0530 that Lieutenant Cummings was instantly killed by machinegun fire as soon as he led the liaison team forward. Four days later his remains, as well as many other Soldier remains, were located and buried by a team led by Chaplain William T. Jones of the 28th Infantry Regiment of the 1st Division. Chaplain Jones’s report stated he buried several men, including Lieutenant Cummings, in a field on the south side of the road leading from Exermont to Gesnes-en-Argonne. However, when the war was over the family of Lieutenant Cummings had no useful information about their son’s whereabouts, all they knew was he was Missing in Action (MIA). The family was notified in April 1919 that their son’s status was changed to Killed in Action (KIA) and in October 1919 the government informed them that their son’s grave was still unlocated. In December 1919 the Red Cross informed Lieutenant Cummings’s parents that their son was buried in Exermont, Department of the Ardennes, in a temporary battlefield cemetery listed as American Cemetery number 209. This was not enough information for a mother and father who still had questions about her son’s death.

In March of 1921 Eliza E. Cummings, stepped up her campaign to learn more about her son’s whereabouts and events of his death. Writing the Army’s Graves Registration Service (GRS), she shows her exasperation that government has sent several dissenting notices to the family claiming her son died on the 4th, 5th, and 8th of October 1918. Additionally, the family had not received any of Lieutenant Cummings’s personal effects. This situation led the family to consider he might still be alive, incapacitate, and helpless in a hospital somewhere. That same month she also wrote to the Commander of the cemetery at Romagne asking for assistance, informing him that the life insurance company had no proof of death to pay benefits to the family. She stated that the government “has misinformed us seems as to get us to give up the search which I never can.”

Eliza Cummings’s campaign generated a new investigation by GRS which caused more confusion about the location of Lieutenant Cummings at the time of his death. The error was GRS belief Lieutenant Cummings was killed between 5 and 8 October 1918. This mistake created a situation where searchers looked for their son’s grave several kilometers north of his actual burial site. Failing to find the remains of Lieutenant Cummings, in 1926 GRS sought out Chaplain Jones to confirm the information of his burial report for Lieutenant Cummings dated 8 October 1918. Chaplain Jones confirmed the grid coordinates of the grave for Lieutenant Cummings was correct and included information of where to find the site, about 200 feet from a ravine on the south side of the road between Exermont and Gesnes-en-Argonne. This information was consistent with a later report in 1926 that Lieutenant Cummings and his men were buried where they had been killed.

In 1930 Eliza Cummings, now a widow, began the process of requesting to make the Gold Star Mother’s pilgrimage to Europe to honor her son. Unfortunately, she was refused the opportunity as Section 1 of the law only allowed for mothers and widows to make the pilgrimage “whose sons or husbands are buried in known graves.” At the time of this decision GRS realized Lieutenant Cummings was killed on 4 October 1918. This date change also corresponded with the location where Chaplain Jones had buried Lieutenant Cummings’s body. Despite this revelation and the statement in 1919 by a company officer that the body had been identified and the grave prominently marked, Lieutenant Cummings’s grave was never located.

In late 1931 the government finally approved Eliza Cummings to make the Gold Star Mother’s pilgrimage to Europe. It appears she was too ill to make the trip in August 1931, so plans were changed to make the trip in 1932. Unfortunately, she had to decline the pilgrimage opportunity again. She thanked the government but explained in a letter dated 31 March 1932 the trip “comes too late in life for me.” She died two and a half months later, never knowing where her son was buried. Lieutenant Cummings’s father had died nine years earlier in 1923. The descendants of Lieutenant Cummings’s four brothers and four sisters to this day still seek the location of Second Lieutenant Eric H. Cummings’s remains.

For his actions on 4 October 1918 Second Lieutenant Eric H. Cummings was recognized by the Commander of the First Division in General Order 54 dated 27 June 1919, for his “courage and gallantry in action near EXERMONT, France … while leading a combat liaison group connecting the First and Thirty-second Divisions” when he was “instantly killed at the head of his men by machine gun fire.” Lieutenant Cummings was also awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palm by the French government for his service and sacrifice.

Doughboy MIA has a Team dedicated to locating missing in action American Aviators of World War One. Second Lieutenant Cummings’s MIA case is actively being researched by this team with the goal of finding and repatriating his remains. Until accomplished, Second Lieutenant Eric Halbert Cummings is listed on the Tablets of the Missing, at the Meuse-Argonne American Military Cemetery in Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, Department de la Meuse, Lorraine, France.

Would you like to be involved with solving the case of Second Lieutenant Eric H. Cummings, and all the other Americans still in MIA status from World War I? You can! Click here to make a tax-deductible donation to our non-profit organization today, and help us bring them home! Help us do the best job possible and give today, with our thanks. Remember: A man is only missing if he is forgotten.