Doughboy Family Memories Etched in Architectural Art

Published: 31 January 2022

By Benjamin S. Dunham

Special to the Doughboy Foundation web site

Brewer_Book_Cover_compressed

My first Brewer purchase was only a copy of a Brewer. I didn’t know it was a copy when I saw it in an antique booth in New Bedford. I signaled to my wife and asked, “Doesn’t this look like one of the cathedrals done by the brother of your great grandmother’s second husband?”

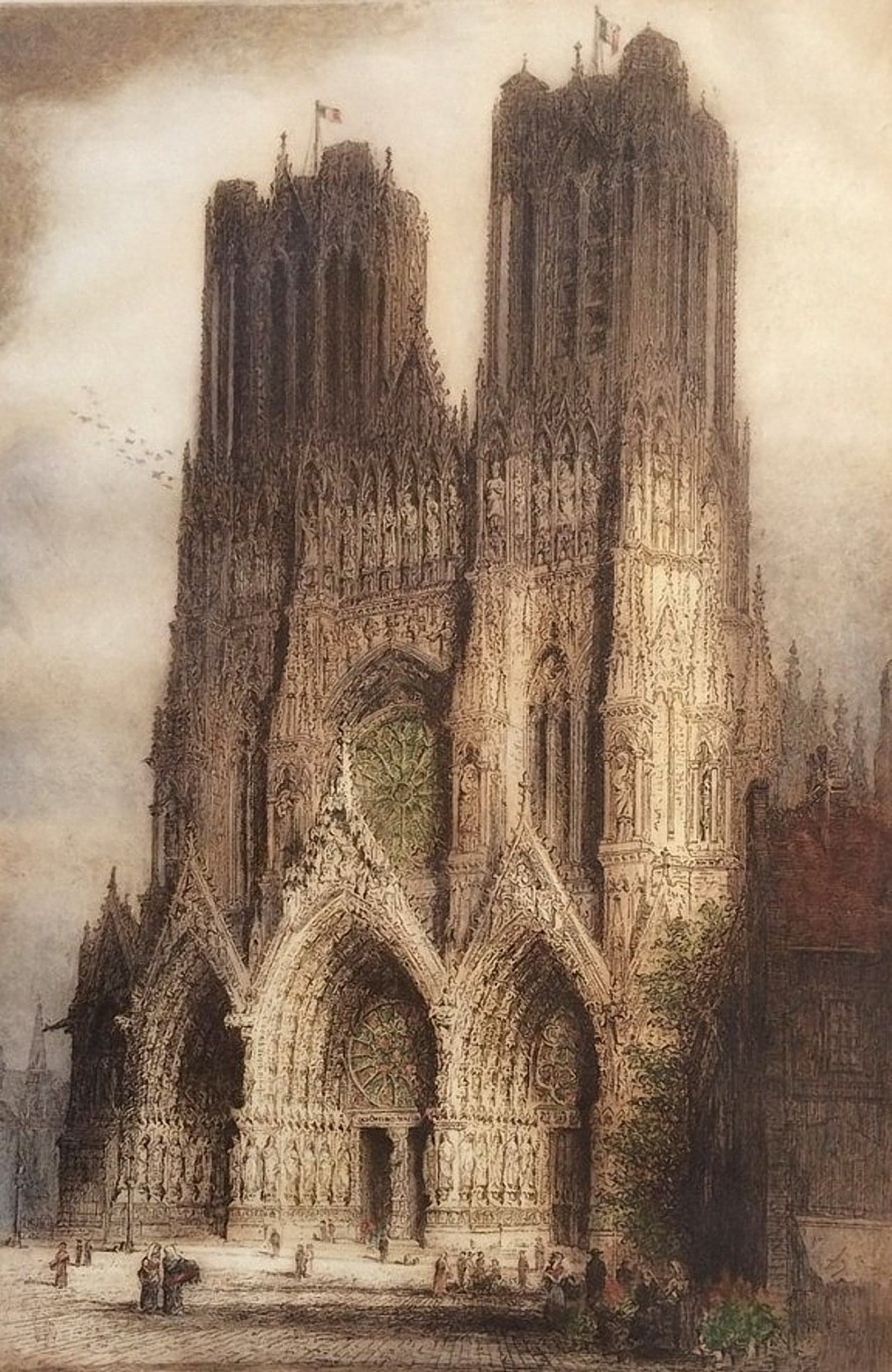

“The West Front of Rheims Cathedral,” an etching by James Alphege Brewer published in December 1914. Inexpensive copies were hung in the parlors of American families in support of the Allied effort.The distant relative was the British artist James Alphege Brewer (1881-1946), and some years later, a family downsizing brought a few of his etchings into our home. After that, during a two-year stretch, I bought just about every Brewer etching that came on the market.

“The West Front of Rheims Cathedral,” an etching by James Alphege Brewer published in December 1914. Inexpensive copies were hung in the parlors of American families in support of the Allied effort.The distant relative was the British artist James Alphege Brewer (1881-1946), and some years later, a family downsizing brought a few of his etchings into our home. After that, during a two-year stretch, I bought just about every Brewer etching that came on the market.

In the process of collecting Brewer etchings, I learned a lot about the artist and his family, and I discovered that the print I found in New Bedford was a copy of his first version of the west front of Rheims Cathedral, published in December 1914. It was this etching that made Brewer’s fame as a young artist, especially in the United States, but at first I didn’t understand its significance in regard to the Doughboys of WWI.

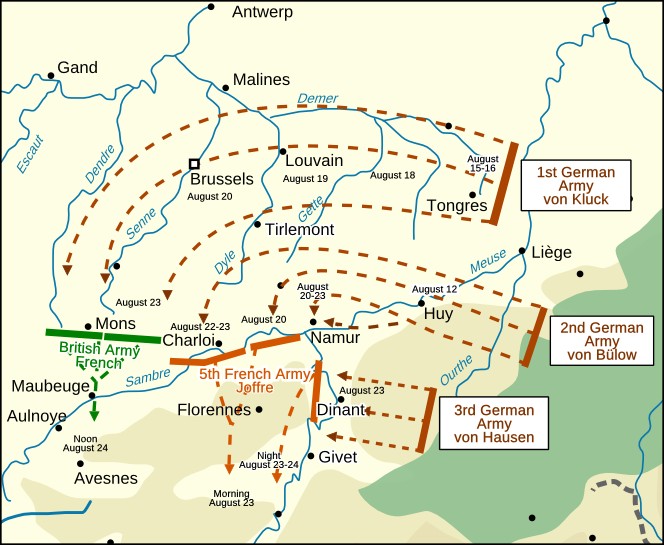

German advance through Belgium, August 1914As my collection increased, however, I began to see a relationship between the subjects and publication dates of Brewer’s etchings and the battles of World War I. The etchings he did in 1914, 1915, and 1916 included threatened and damaged historic buildings in Brussels, Antwerp, Namur, Dinant, Huy, Louvain, and Malines, all of which are identified on a map showing the course of the German attack.

German advance through Belgium, August 1914As my collection increased, however, I began to see a relationship between the subjects and publication dates of Brewer’s etchings and the battles of World War I. The etchings he did in 1914, 1915, and 1916 included threatened and damaged historic buildings in Brussels, Antwerp, Namur, Dinant, Huy, Louvain, and Malines, all of which are identified on a map showing the course of the German attack.

When I compared these magnificent edifices to the photographs of the ruins that resulted from the wartime damage, I realized that Brewer’s wartime etchings showed the buildings as they once were, not as they appeared after the attacks. The images must have been captured in some way before the war began.

Brewer could have seen newspaper articles in 1913 about the course of a possible invasion of Belgium. For instance, in September 1913, after the Belgians had finished their summer war games, the Paris correspondent for The Times reported that the French grumbled about the defensive exercises near Dinant and Namur. This, the French thought, was a course that was “considerably to the north of that which a German army would follow if it violated Belgian neutrality.” But only a year later, that was exactly where the Germans attacked.

Reading reports like this in 1913, Brewer might have been able to envision a series of etchings showing scenes from the heart of Belgium. As Barbara Tuchman pointed out in The Guns of August, the Schlieffen Plan (even with Moltke’s adjustments) was based on a German advance through the whole of Belgium. Schlieffen said, “Let the last man on the right brush the Channel with his sleeve.”

The impact of Brewer’s etchings in America was almost immediate. A March 1915 ad for Closson’s art gallery in the Cincinnati Enquirer was headlined “Etchings from Warring Europe,” and the text continued, “We have just received about a dozen new subjects by Mr. Brewer, some of which were sketched in cities mentioned in the war despatches of recent months.” More would follow throughout the war. As a group, these etchings—which were, in essence, anti-war or, at the very least, nostalgic for an earlier era of peace—argue for their inclusion in surveys of important and influential political art.

Two of Brewer’s etchings—the 1914 etchings of the west front of Rheims Cathedral and its interior—had the largest impact because they were published without an American copyright. They were sold in the United States at a reduced price by Emil Jacobi as “Jacobi Re-proofs,” and other lithographic copies were sold at even lower prices by a number of American printers. These copies were proudly hung on parlor walls in solidarity with the Allied cause and as a remembrance of the devastating cultural losses inflicted by the onslaught of war. They became the “go to” art for thousands of people in America who were emotionally involved with the progress of the Allies, whether for cultural and patriotic reasons, or later, because they had a family member serving in the war.

I thought this might be true because of the wide availability of prints of Brewer’s etchings at this time and the way they were promoted as war mementos in ads and other notices in journals and newspapers. But I had no proof, not even anecdotal evidence.

I thought this might be true because of the wide availability of prints of Brewer’s etchings at this time and the way they were promoted as war mementos in ads and other notices in journals and newspapers. But I had no proof, not even anecdotal evidence.

Then, listening to me talk on the phone about my latest acquisition of a Brewer cathedral, one of our dearest family friends said, “You know, I have an old print of a cathedral in my basement. It used to hang on the wall of the house I grew up in. I’ll try to find it.”

Sure enough, it was a copy of Brewer’s 1914 “West Front of Rheims Cathedral,” the same etching that made Brewer famous in this country. My friend remembered that it was practically sacred in his house. His uncle, a mentor to his father, fought in France with the American Expeditionary Forces, and he imagined that was why his parents held this print in such reverence.

He sent it to me, in its gold-leafed frame, as a gift, one that had more importance to me for what it represented than for its modest value as a print. It said something quite wonderful about Brewer’s wartime etchings and the impact they had on people in this country.

Almost a year later, I was telling this story to a new acquaintance, and he remembered a framed cathedral print in his attic. It turned out to be another copy of Brewer’s 1914 Rheims Cathedral etching, and it had been hung in his great aunt’s house. His great uncle was killed fighting in WWI, and members of his family still occasionally go to visit his grave in one of the American cemeteries in Northern France. A print that had been totally overlooked for some 40 years was now suddenly resonant with family history.

The most recent instance was during a local exhibition of Brewer’s wartime etchings when the owner of a local boatyard showed up with a large copy of Brewer’s 1914 “West Front of Rheims Cathedral,” saying it had been hung in his parents’ house in remembrance of a great uncle who had fought in the war.

The local exhibition was in connection with the release of my book, Etched in Memory: The Elevated Art of J. Alphege Brewer. Based on the material at my website (www.jalphegebrewer.info), it’s the first illustrated study of the life and career of J. Alphege Brewer (1881-1946), which continued for more than two decades after the end of WWI and produced over 300 etchings. Chapters on Brewer’s life story, techniques, and the artistic context for his war etchings are included, as well as a catalog of his known etchings.

Learning more about James Alphege Brewer and connecting with people whose families have been impacted by his impressive war etchings has enriched my life in many unexpected ways. What Abbé Morel said of the “Miserere” series by Georges Rouault is even more appropriate for Brewer: He found a way “to participate in the battle by rebuilding what the battle had destroyed in man.”

B enjamin S. Dunham has enjoyed an active career in arts administration and journalism. In retirement he collects the etchings of James Alphege Brewer, curating exhibitions and speaking about the British artist’s life and work. z

enjamin S. Dunham has enjoyed an active career in arts administration and journalism. In retirement he collects the etchings of James Alphege Brewer, curating exhibitions and speaking about the British artist’s life and work. z