The Doomed Doctor and the Most Famous Poem of World War I

Published: 1 September 2022

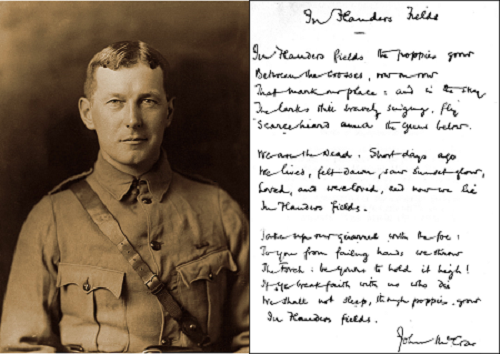

Flanders_Field_McCrae_500

By Michael E. Ruane

There are stories that may not have made the textbooks, offbeat tales of people and events, fragments and glimpses of surprising lives. This is one in a series of vignettes from the forgotten corners of history.

On Sunday morning, May 2, 1915, Lt. Alexis Helmer, 22, of the Canadian field artillery, stepped out of his bunker on the Western Front and was hit by a big German artillery shell.

What was left of him was gathered up in sandbags, the story goes, and buried that day on the battlefield.

A death like Helmer’s was commonplace during World War I. But his became famous because of a poem written in his honor, the most popular English-language poem of World War I.

One hundred years ago next month, a Canadian officer and poet, Lt. Col. John McCrae, drafted these lines after reading the “committal service” over Helmer’s grave.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; by yours to hold it high

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

McCrae, then 42, was a highly regarded physician who had written a textbook on pathology and had once worked at Baltimore’s Johns Hopkings Hospital.

A native of Guelph, Ontario, and a veteran of the wars in South Africa, he became an officer and surgeon in the 1st brigade, Canadian field artillery, during World War I, according to the Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

The brigade was in the notorious Ypres salient, an eastward bulge in the Allied lines in Belgium, when the Germans launche a massive attack using poison gas in April 1915.

McCrae and his comrades were in the front lines for 17 days, and he recounted some of the “nightmare” in a diary.

“This night, beginning after dark, we got a terrible shelling, which kept up till 2 or 3 in the morning,” he wrote on April 25. “We must have got a couple hundred rounds, in single or pairs.”

“Every one burst over us would light up the dugout, and every hit in front would shake the ground and bring down small bits of earth on us,” he wrote.

On May 2, he wrote: “Heavy gunfire again this morning. Liet. Helmer was killed… a very nice boy… His girl’s picture had a hole right through it – and we buried it with him. I said the Committal service over him, as well as I could from memory. A soldiers death!”

Witnesses later recalled seeing McCrae sitting in an ambulance either that day or the next composing the poem, according to historian Dianne Graves’s biography of McCrae.

McCrae had published other poetry, and submitted “In Flanders Fields” to The Spectator Magazine, which rejected it.

Undaunted, he sent the poem to Punch magazine, which published it in December 1915.

It was an instant hit.

“It [gave] expression to a mood which at the time was universal, and will remain as a permanent record when the mood is pass away,” the Canadian essayist Andrew Macphail wrote in 1919.

Soldiers learned it. (the word “grow” instead of “blow” is sometimes used in the poem’s opening line.) It was used to promote the sale of war bonds. And it helped make the red poppy one of the war’s great symbols of loss.

But not everybody has loved “In Flanders Fields.”

The late literary critic Paul Fussell found the poem marred by “familiar triggers of emotion,” and “recruiting poster rhetoric.”

Fussel believed British soldier-poet Isaac Rosenberg’s “Break of Day in the Trenches,” was the greatest poem of the war.

McCraw never quite recovered from his 17 days in the Ypres trenches. A victim of asthma for much of his life, he contracted pneumonia and meningitis and died on Jan. 28, 1918, in a hospital in Wimereaux, France.

He was buried there with military pomp the next day.

Lt. Helmer’s battlefield grave, meanwhile, was trampled by subsequent fighting and has disappeared.

His name appears, with 54,000 others, on the Menin Gate Memorial in Belgium to those killed, but never recovered, in the Ypres salient.