Comity, Rivalry, and the Real Drivers of War

Published: 21 July 2025

By Eamonn Bellin

via the Law & Liberty website

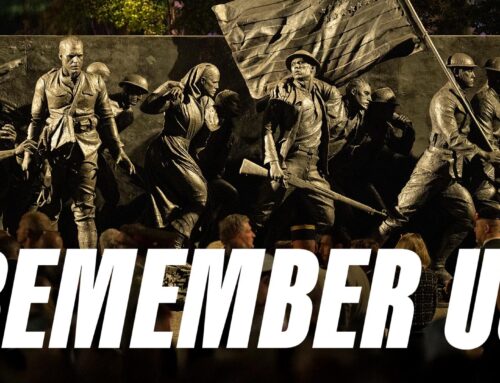

German,Ww1,Soldiers,With,Machine,Gun,40,Meters,From,The

German soldiers sit in a trench during the First World War. (Shutterstock)

The Great War’s example should discourage us from reducing Sino-American tensions to ideological differences.

Winston Churchill reflected that “no part of the Great War compares in interest with its opening.” A century later, the origins of the First World War should still interest us for what they reveal about the causes of great power conflict. An underappreciated insight from the Great War is that anxieties incited by imbalances among “rising” and “ruling” powers—popularized by Graham Allison as the “Thucydides Trap”—can overcome the stabilizing influence of shared interests, institutions, and ideologies. Too often depicted as an ideological clash of democracies against dictatorships, the Great War was in fact fought between liberal states with similar societies, interwoven interests, and cooperative habits. It was fratricide, not kulturkampf. Today, the example of the Great War should discourage us from reducing Sino-American tensions to ideological differences or assessing common interests and cooperation as a means of insurance against war. In 1914, a close-knit community of states succumbed to the anxieties that provoked a great power war. Washington and Beijing today have an even narrower margin to avoid Armageddon.

What Caused the Great War?

Graham Allison’s Destined for War examines (among other cases) prewar Anglo-German relations through the “Thucydides Trap,” a prism derived from the ancient Athenian’s dictum that “the growth of the power of Athens, and the alarm which this inspired in Sparta, made war inevitable.” Allison subscribes to Thucydides’s judgement that fear, honor, and interest drive political action. His analysis suggests fear is an especially salient motive in fin de siècle geopolitics. He contends Germany “rose further to threaten British industrial and naval supremacy,” bringing disquiet to Whitehall. He cites British unease that the growing German navy seemed intended for, in the Admiralty’s assessment, “war with us.” In turn, he situates Germany in a worrisome position between an aggressive Russia and an anxious Britain. Specialists on the outbreak of the war, like David Herrmann, Christopher Clark, and T. G. Otte support Allison’s attention to fear, examining how fear of the future and fear of losing allies drove Europe towards conflict.

Allison omits ideology from his analysis, the most commonly invoked cause of the Great War, even by those who waged it. In 1913, General Friedrich von Bernhardi’s Germany and the Next War asserted Germany had been “robbed” of its natural boundaries, had a duty to “check the onrush of Slavism,” and that “war is a biological necessity.” David Lloyd George pronounced in 1914 that Britain fought to rescue Europe from “the straight road to barbarism” presented by “the Prussian military caste.” In 1917, Woodrow Wilson branded the Central Powers “autocratic governments backed by organized force which is controlled wholly by their will, not by the will of their people.” Since then, Barbara Tuchman has portrayed Wilhelmine Germany as infatuated with militarism. Fritz Fischer and A. J. P. Taylor made the Great War the culmination of Germany’s nineteenth-century Sonderweg from liberalism to authoritarianism. Robert Kagan attributes Germany’s encirclement “solely” to its domineering Weltmacht, or pursuit of world power. Ideology also matters to scholars sympathetic to Germany. Whitehall Germanophobes for Christopher Clark, Tsarist grandiosity for Sean McMeekin, and death-obsessed modernism for Modris Ekstein shadow the road to war.

The World of Yesterday

In truth, however, pre-war Europe’s ideological differences were modest. Excepting republican France, fin de siècle Europe’s great powers were governed by combinations of crowned heads, elected legislatures, and written constitutions. Britain and Germany particularly resembled this norm—and one another. Kaiser Wilhelm was “Cousin Willy” to King George and doted on by his grandmother, Queen Victoria. Germany’s Reichstag and Britain’s parliament were elected on broad franchises. German ministers were not legislatively accountable like British ones, but both needed legislative assent to borrow, raise, and spend money. Independent judiciaries administered law in both. The 2.5 million union members in Germany and 2.2 million in Britain were easily the continent’s largest labor movements. Traditional elite vestiges, like the Prussian Landtag or the British Quarter Sessions and House of Lords, attracted resentment but, apart from the Lords, avoided reform. Social detente was attempted to ameliorate class conflict. Otto von Bismarck’s “Practical Christianity” established the world’s first social welfare regime and inspired the British Liberals’ “People’s Budget.” Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg’s (unsuccessful) Prussian Landtag reform aimed to mollify labor. More effectively, the British Liberals partnered with the fledgling Labor Party in the 1906 election.

“Nationalism” did not prevent continuous Anglo-German governmental consultation on security questions like warship construction. Anglo-German naval officers often fraternized at festivals like “Kiel Week.” Moreover, when war came, it was greeted with ambivalence. Most British unions reacted with an “industrial truce,” while Prime Minister H. H. Asquith secured parliamentary support for war only by dividing his Liberal Party. In Germany, unions held massive anti-war demonstrations before heeding Kaiser Wilhelm’s plea for inter-class Burgfrieden to defend Germany against reactionary Russia. Rather than reflect a cleavage between democratic and autocratic societies, Germany and Britain were comparable ones with similar concerns and interests.

→ Read the entire article on the Law & Liberty website here:

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.