A brief history of the WWI Espionage Act in the Pacific Northwest

Published: 16 June 2023

By Knute Berger

via the Crosscut web site

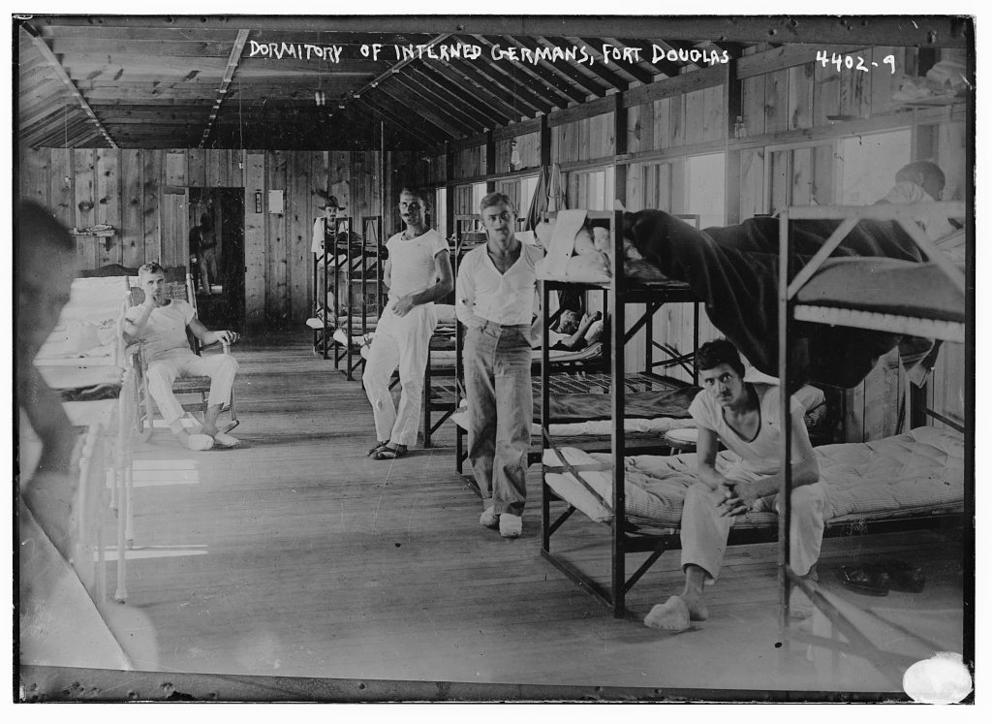

Germans interned Seattle 1917

During World War I, around 4,000 Germans and German-Americans were interned. Those arrested in Seattle were placed at Fort Douglas in Utah.

The WWI-era law former President Trump is accused of breaking has a controversial past, with a first few prosecutions tracing back to Seattle.

he Espionage Act is in the news with the indictment and arrest of former president Donald Trump for his handling of classified material after leaving the White House in 2021. He is not accused of spying, which can be a little confusing given the name of the Act he is being prosecuted under. Yet, even during its early years, the Espionage Act covered an ever-widening range of behavior beyond spying that was said to put the nation’s security at risk.

The Act was passed into law in 1917 just after the U.S. entered World War I. It was a time when alarm over immigrants and “enemy aliens” and acts of terrorism targeting the homeland was at a fever pitch. In 1918, the Act was amended to include sedition, which, into the 1920s, was used to justify political harassment, book banning and disloyalty, among others.

Many Trump supporters contend that the Act is being employed in this case for a political hit job. Yet the indictment unsealed by Department of Justice special counsel Jack Smith earlier this week effectively paints the former president as a security risk. Whether his actions merit punishment will ultimately be up to a jury. What we do know for certain is that more questionable cases involving the old Espionage Act resulted in convictions. And a number of those occurred in the Pacific Northwest during the early days of its enactment.

The Act was partly a response to a prewar terror campaign by the German government, which was conducting a shadow war on American soil as early as two years before the U.S. engaged in the overseas conflict. In May 1915, for example, a massive explosion off Seattle’s Harbor Island and a railcar fire in Tacoma were widely regarded as acts of German sabotage to prevent supplies and war materiel from being shipped to Germany’s enemies. Those shipments were intended for Vladivostok in Russia, then an ally of Britain and France against Germany.

The Pacific Northwest was considered to be of strategic importance at the time. West Coast ports and shipping were potential targets for sabotage. The docks and shipyards were stocked with socialists, trade unionists and immigrant workers suspected of wanting to monkey-wrench the capitalist supply chain.

Washington state formed a kind of soft underbelly to British Columbia, which was already at war with Germany. The Act gave the U.S. a tool to use against agents and spies who might work across the border.

Then, during U.S. involvement in the war, the Act protected important installations like the Naval shipyard in Bremerton, essential to the war effort along with Puget Sound’s private shipbuilders. Points around the Salish Sea bristled with forts and gun emplacements, like Fort Worden near Port Townsend, to protect shipping. Lumber for the war effort was harvested and milled here for the national defense and sent to allies.

Early revisions to the Espionage Act expanded its reach to include anyone thought to undermine the American war effort. Legitimate concerns quickly merged with ethnic prejudice and public hysteria to crack down not only on saboteurs, spies and German sympathizers, but anyone who voiced opposition to the war effort.

Read the entire article on the Crosscut web site.

External Web Site Notice: This page contains information directly presented from an external source. The terms and conditions of this page may not be the same as those of this website. Click here to read the full disclaimer notice for external web sites. Thank you.